Craft Advice with Karie Fugett

On prologues, how to write about people who were unkind to us, defining memory, writing with children, and not overthinking

Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

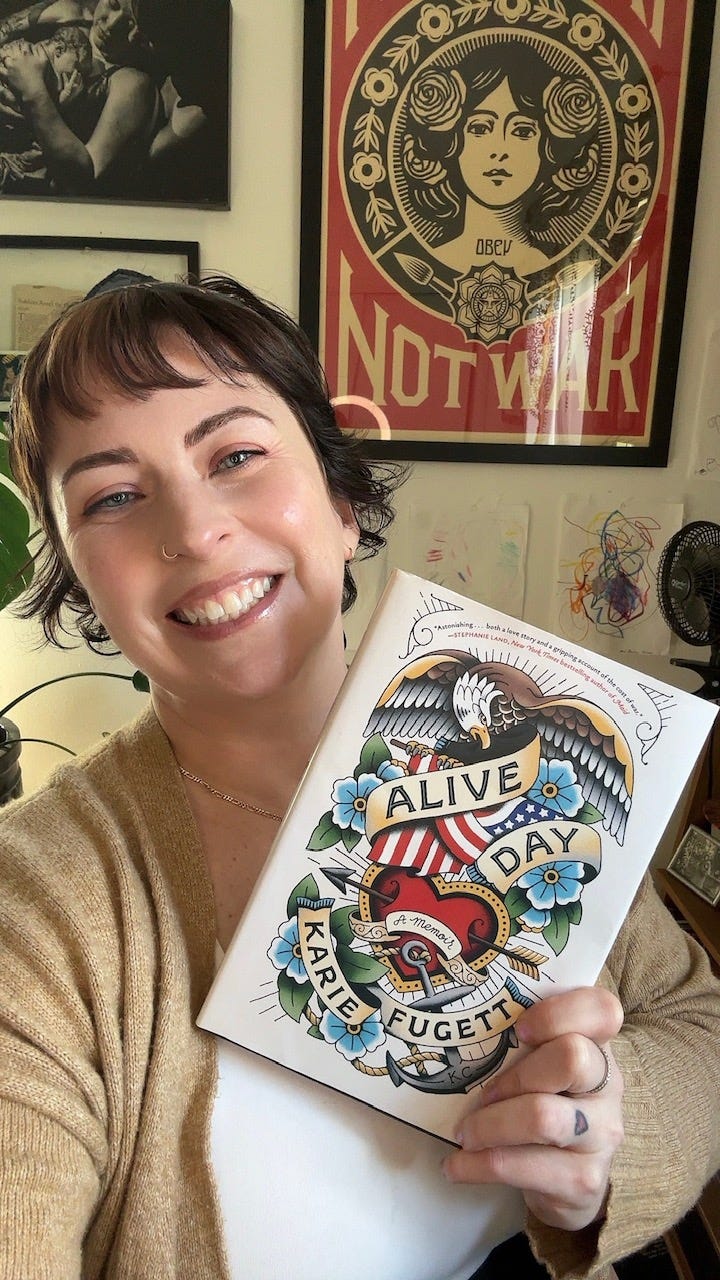

From the moment I read

’s essays about her experiences caring for her husband, a solider who had been injured in Iraq, both before and after having his leg amputated, I felt the cells in my body rearrange themselves. She wrote with such honesty, care, tenderness, insight, and vision. My parents grew up in London during WWII and I grew up on their stories; plus, I’ve written a novel based upon their experiences requiring massive research, so I thought I knew a fair bit about war — but Karie’s writing took me deeper and wider.So I was excited to read her debut memoir, Alive Day. As I wrote to Karie when we were making arrangements for this interview: “Your book is so beautiful! I am just bowled over. Even better than I was imagining it would be… and I was imagining pretty fucking spectacular!”

The prose is clean, tight, focused, and lean yet it carries such rich and heart-tending emotions. Karie doesn’t shy away from letting us experience what she experienced, yet she also tends to us with her thoughtfulness and clarity. There’s so much drive to this story, so much solid old-school storytelling. Ultimately, it’s a book of hope but hope that is hard won.

Alive Day has garnered a starred review from Kirkus Reviews and was selected for Book of the Month. Karie’s work has been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Harper’s Bazaar, and more. She holds a BA in creative writing from the University of South Alabama and an MFA in creative nonfiction from Oregon State University.

If you missed part one of our conversation, you can read it here.

I learned a lot from Karie’s insights into craft. I think you will, too! Enjoy!

xJane

❤️ Massive, ongoing gratitude to all the paid subscribers whose support for Beyond not only allows me to keep writing this newsletter, it also supports The DeTommaso Dogs. Our monthly donation helps keep these sweet doggies and some kitties off the streets, healthy, and into their forever homes. Thank you! ❤️

Where do you write?

I do lots of writing in my bed. I also write at my desktop. I got this pretty green Mac desktop, because I realized writing in my bed constantly is not healthy. I also wanted to separate bed from work a little more. I like that because it does feel like, “this is work time.” And when I'm done, turn it off, walk away. But I still write in my bed when I feel like it.

Do you write every day?

Not right now.

Do you feel guilty on the days you don't write?

Not anymore. I wrote a whole book! It's coming out soon, so I'm doing all these other things outside of writing that feel productive and not easy. So I’m just giving myself that, “if I want to write, I'm going to write, and if not, I'm not.”

But I'm reading more, and that includes reading other people's manuscripts to blurb their books, and I'm happy doing that right now. I just had a couple of op-eds come out because veterans have been in the news with the DOGE stuff. I'm working on a thing for The Atlantic. But not every day. I'm fine with that, for now.

Your book opens with a prologue (which I love!), and prologues are catching a lot of grief these days. Why did you decide to go that route?

I've seen the conversations around prologues. It made me second guess myself a little, but this was a very long process for me getting from “I want to write a story” to a published book. I didn't have a college education. I really didn't even know what an essay was. I had to hustle and learn everything from scratch.

The prologue is a piece of the original first chapter that was pulled out because my editor thought it felt separate. By the time we got to that point, I was like, “Okay, editor, I'm not overthinking things like this.” I trust my editor.

Some people aren't going to like it, and that's fine. I can't get everyone to like my book.

Why did you pick that scene?

From a craft perspective, grabbing someone's attention. Also setting the tone: these young kids and guns are a theme throughout. I wanted to make sure that the military was established before backing up.

You mention that it took a while to write the book. Can you talk us through that journey?

I had a blog called Wife of a Wounded Marine. At that time, blogging was really popular for military spouses. It's this world that often does feel isolating, and through blogging we were able to build these communities and tell our own stories from our perspective without anyone telling us how to say it.

I started doing it with the intention of keeping people updated about what was going on in the hospital. So it was just a day to day, “Hey, we're here doing this, blah blah!” I didn’t expect anyone to read it. Fast forward a few years, and tens of thousands of people were reading it. I took it down eventually because it's so embarrassing. It's like when you look back at an old diary, and you're like, “What was I thinking?”

But at the time, it was an outlet for me and planted a little seed in my head. I was like, “Oh, people are listening and not hating this, and I'm enjoying it.” That was around 2008. I continued a couple of years after Cleve died.

Mostly I struggled back then with feeling like I was capable of doing anything, really. Then I thought maybe I could write. I was thinking more like journalist. But when I started college, there was a tiny part of me that thought I could maybe write a book about what I just went through. I’d looked for those books, and they were nowhere. I was like, “Why is nobody talking about this.”

I didn’t love journalism because it felt stifling. I would write these long, wordy, descriptive things, and then they'd chop it down to 800 words. And I was like, “this is terrible.” And then Jesmyn Ward had a memoir class at this little school in Mobile.

I saw that in the acknowledgments. I was like, “Oh my god! Karie studied with Jesmyn Ward!”

She was in the middle of working on her memoir Men We Reaped. I took two classes with her. That was where I wrote my first original chapter for this book. I didn’t realize it; I was thinking of it more as an essay that I wanted to submit places. Once I saw that it could be turned into a story, that I could write dialogue and create scenes out of all this stuff that I just experienced, I got hooked.

What year was that?

Probably 2012.

From there, I was practicing these tools that I learned, and realizing “I’m not bad at this.” I won some awards in our creative writing department. And I was the editor-in-chief of their literary journal. I very quickly just took to it.

By the end of my undergrad, I was very much thinking about writing a book and taking it more seriously – because other people were taking me seriously.

When did the actual book start? When did you write the proposal and get the agent?

The process was weird. What I submitted to the MFA program was the original chapter to this book, which is now somewhere stuffed in the middle and stretched out. Also with Jesmyn Ward’s recommendation, which I feel like could have gotten me into anywhere at that point.

What year did you start your MFA?

2016. I went in with the purpose of writing a book. I took a few workshops and tried new techniques, new ideas—stretched the limits a little bit. I was determined to leave, if nothing else, with the skeleton of a book that I’ll work on after. That ended up being my thesis. The thesis, though, was messy. There were a lot of memories that I turned into scenes without any connection between them. Then I ordered them in time. I graduated in 2018.

I was adamant about publishing pieces of what I was writing, too. It kept me motivated. It's exciting to get an acceptance to a literary journal; it reminded me— “Other people can see this. There's maybe a purpose to this.”

One of the visiting writers, Matt Young, also writes about military. His book Eat the Apple is so good. It's funny and poetic. We bonded because he's a Marine. I interviewed him for our school newspaper, and we ended up keeping in touch, and he started following my work. When I published stuff, he would share it. I published one essay in this small magazine, and he insisted on sending it to his agent. I got lucky. I did not have to have a proposal ahead of time.

That’s wonderful.

The agent read that essay. He called me to see if I had been thinking about a book, and I was like, “yes.” He thought we could turn it into a proposal. He signed me that week. Soon after, Economic Hardship Reporting Project found me on Twitter and on an essay for Washington Post that got quite a bit of attention. Everything was happening at the same time.

I love when that happens!

Soon after that, I got a New York Times piece in January, and then in February my book went on proposal, and it sold.

Yay! How long did it take you to write the book?

I sold it in 2020. I was supposed to have it finished by 2022. But then COVID happened. And I also had a kid, so I took two years off. Really, though, from my thesis to proposal, that took about eight months to get it where we needed it. And then, from proposal to final book, if I'm only considering the time that I was actually sitting down writing, it was probably a year combined. But it was spread out. I was really stressed out. It wasn't an easy book to write emotionally.

What kind of toll did it take on you going back through all of that?

I wrote different versions of things in undergrad and scrapped them, and rewrote and scrapped them, and then rewrote again in my MFA. There was a lot of rethinking, retrying. It was especially hard then, because I was revisiting those things for the first time, and trying to understand them on a different level. When you're writing a memoir, you're asking yourself, Why does this matter? What is this connecting to outside of your own experience? Or what did you learn?

But once I really started—I wrote the bulk of the book not this last year, but the year before—it just started coming out. I've been thinking about this stuff for so long that by the time I had to sit down and get it out, it wasn't affecting me as much.

That final author's note was hard to write. Some of the childhood stuff was really hard to write. I avoided that. That was some of the last stuff that I wrote, which probably seems strange, because it's not as heavy.

Oh god, no! The childhood stuff is heavy.

That was stuff that I was like, “do I really have to go back to that?” It was tough.

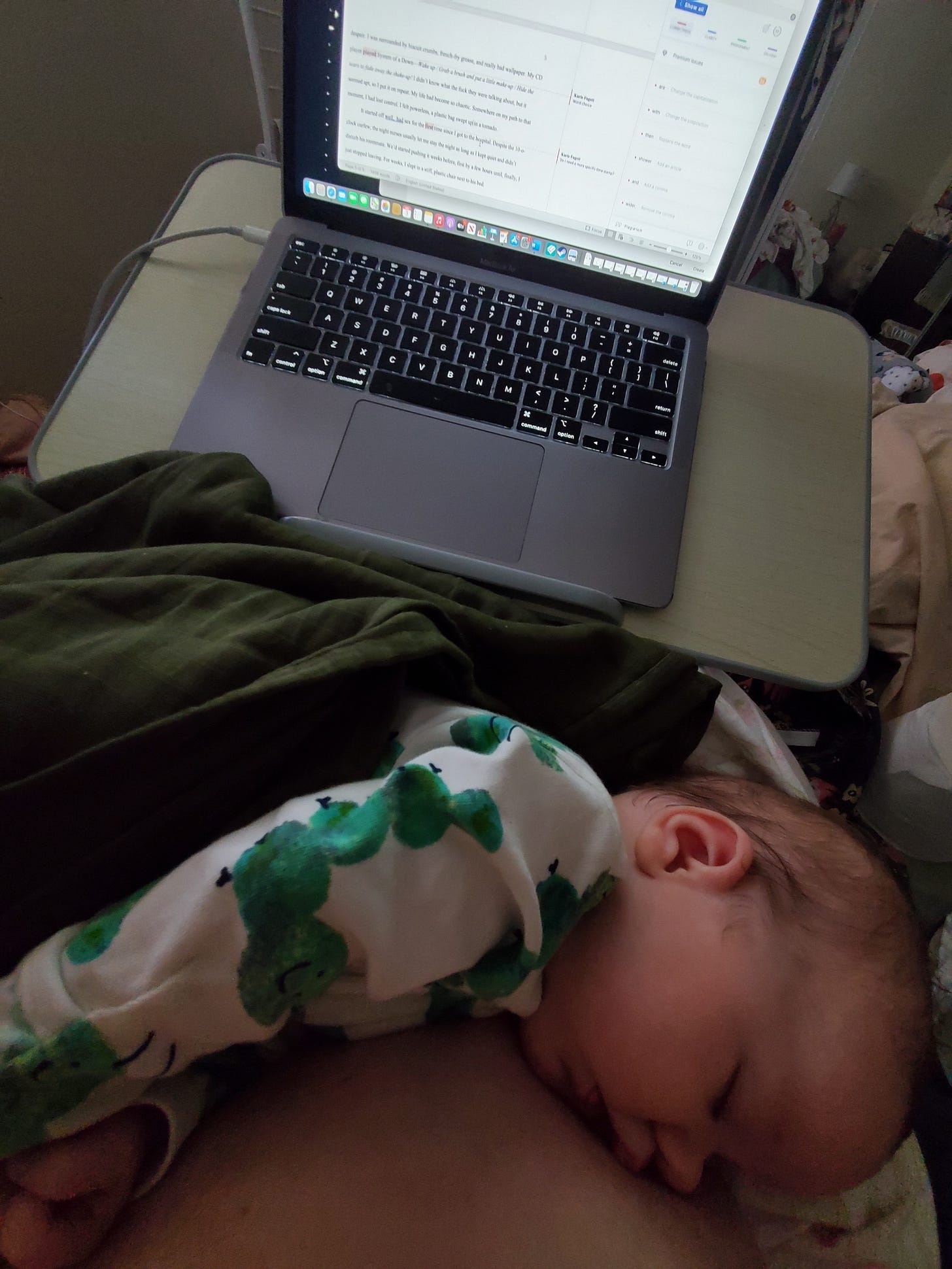

How did you balance writing with having a child?

I didn’t. I was pregnant. I was like, “I'm not writing. I'm just going to have to give you the money back because I don’t think I can write this.” I had an email that was very similar to that: Should I just pay you back? How does this work?

I was dealing with the postpartum stuff. I didn't realize it at the time. My editor was so supportive and part of it was probably COVID. Everything was on hold. The publishing industry was in the midst of changing. My editor was like, “take two years off.” And I did.

Did you think about it during that time?

I did think about it, but I really, really, really absorbed myself into being a mom, and I feel lucky that I was able to do that. Everything was about her. Because it was COVID, we were very isolated. It was just me and her all the time. It was stressful, but I also loved it, and it felt important to me. I gave myself permission to just be a mother. I picked the book back up when I had to.

When the two years were up, your daughter wasn't at school age, so how were you balancing that?

We moved back to Alabama where we have family and good friends and to help out. That has made a huge difference.

Speaking of which, you needed to write about friends and family members, amongst others. How difficult was it to get all that on the page? And did you show them the pages before publishing?

It depends on the person. My sisters were given copies of our childhood, anything with scenes of them. Kirsten didn’t care —she wasn’t in it as much. Kelsey started reading it, and it triggered too much. She got to the point where she was like, “You know what, I trust you.” She didn’t read through it.

With Carson, that’s not his real name, I’ve always been like, “Let me know what’s off limits.” And he’s always been full-on like, “Write whatever you need to write. I trust you.” Super supportive. Same with Britney—she’s always been good with it.

Cleve’s family does not know. They knew that I was blogging and that I was going to school to write a book.

I wondered with the mom. She seemed like a tricky one to get on the page.

They're the ones I worry about the most. If I’m being honest, I was kind about her in the book. I tried hard to balance truth with protecting her a little bit. I have a clearer idea now of how she looks—now that I’ve done my audiobook and was reading it out loud, and I have renewed concern that she looks too harsh or too negative still.

The way I read her was that she does seem to be a difficult person who you portrayed with great kindness. She sounded very controlling.

There was a lot more that happened. I get to a point of forgiveness at the end. But I do not talk to them anymore, for my own sanity. I tried really hard for years to reach out and visit and, despite everything, I wanted to feel like there was some kind of peace there. But I needed to also allow myself to walk away because I was stuck in this toxic thing where I would never get the approval that I wanted in the relationship that I wanted.

So I was like, “how do I write them out of this?” Part of the reason it took me so long to get words on the page was, “What am I going to do about his family?”

That would be hard.

I finally decided there's no way to write it without them in it. I can't write them out of the funeral. I tried early on. I didn’t mention them at all, and every single time I brought it to a workshop, they were like, “Where are y’all’s parents? Where are your families? Why is it just you?”

It must have also been hard to write your own parents, because they were not very supportive at times where you really needed them.

My parents were really difficult to write. I got some peace with that. We don’t talk anymore. After I had my kid, some things happened, and I found my final line. I was like, “Wow. You're not interested in getting to know the most amazing person on the planet. This is too toxic for me. I need to separate myself and find family and acceptance and whatever elsewhere, because I'm wasting too much time pouring into you and never getting it back.”

After that I allowed myself to write the story that I needed to write. I didn’t say everything. I tried to show readers some good sides and keep out some of the worst stuff to protect them. But this is my story. This is what happened, and it affected me. The way other people treated me had an effect on how I reacted to other things later down the line. Ultimately, I have a right to my own story, but I also want to tell it in a way that feels like I’m being gracious and not doing it to harm people.

I think you did a phenomenal job of that.

That was a huge fear of mine constantly. How to portray Cleve kept me up at night. I was really, really, really afraid of him coming off as the enemy, the bad guy.

There’s that Anne Lamott quote: “If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” Yet when it comes to applying that, for most of us, at least, it’s not that simple. And there are other people involved. For instance, when you're writing about your parents, that potentially impacts your sisters.

Totally. I ran a lot of this stuff by my sisters. Like, “How do you remember this?” For the most part, they're like, “Yes, this was our childhood.” Of course, there’re details here and there that she's like, “Oh, I remember you had bracelets on and you ripped the bracelets off,” stuff like that I had to grapple with. Do I go with her version or mine? I decided, if it’s little things like that, I’m sticking with mine, because that’s my truth. And there’s no one that can really determine which one of us is right anyway. There’s no one videotaping that memory. In general I wanted to know, “Do you think this captures the vibe of our childhood? Do you remember this happening?”

One of the harder things for me to write was when I was sexually assaulted as a child by the neighbor. There was a point in my life where my brain blocked it out. It was this fog-like dream that I was able to write off. I learned more about that kind of blocking out later. By my late teens, it was all I could think about, and it really messed with me. But then I was questioning if it even happened. To be sure, I talked to my sisters. Like, “Do you remember a guy who looked like this? Did he have a son?” All these details. And they’re like, “Yes.” And they gave me more details. I was like, “that’s all I need to know.” My sisters were really useful for confirming a lot of the childhood stuff. It also made me feel better to know that I had their stamp of approval, especially when it came to our family.

I can understand that! Your book is so tight. How did you know this scene is included and that one isn’t? Was there a lot more of the book and things got cut back, or did you intuitively know what to include?

A lot of it was intuitive. I wasn’t confident in that intuition at first. But Jesmyn said something like, “Look for the gold nuggets.” She was saying if you cannot get the memory out of your mind, if it’s vivid, it’s sticking with you, it’s probably important.

It was helpful for me to not overthink it. To pay attention to what memories stuck out to me, turn them into scenes, and then move on, and then collect those, put them in order, and then see what I’m working with. I was able to see a little bit of a narrative arc, and also was able to see things that just weren’t fitting.

Once you had that whole string, what about the connection tissue? Did you need to sew them together?

I did. The connective tissue isn’t my favorite part. I had to redo it over and over. But it helped for me, once I had the scenes in order, to sit down and go, “What am I trying to get across?” And write that down so that I stay focused on that. Because if you just have a bunch of scenes, it’s easy to turn it into anything. But I was like, “this is what I’m trying to get across, so whatever I do needs to focus on that.” And then I picked the scenes that worked toward that. And chapter by chapter, just did it.

A lot of writers read Beyond. Is there a prompt that you rely on or one that you really enjoy?

Not overthinking. If you have a blank page in front of you, especially if you’re writing memoir and you’re not sure where to start or where it’s going to end — just start with a memory that’s so vivid you cannot let go of. Get it out in as much detail as possible. What do you smell? What do you see? Why does this matter to you? What are people saying? Really flesh that out. I feel like, for me anyway, that takes care of the blank page problem. And I like writing scenes — it’s fun.

If you enjoyed this Craft Advice with Karie, you might also enjoy this one with

:

Wow, love every part of this interview and can't wait to read Karie's book. So interesting to hear about the two year break - the fact that she had to take a two year break and did find the strength to come back to it is inspiring (And: it's possible that all that subconscious percolating actually helped on some level?) ~ All of this is more proof that everyone's process/journey is different.