Always Something Beautiful Out There: A Conversation with Karie Fugett

On war, being a caregiver to a wounded husband at twenty-one, self-care, waking up to trauma, learning to like yourself, and the healing magic of friendship

Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

I can’t remember when I first became aware of

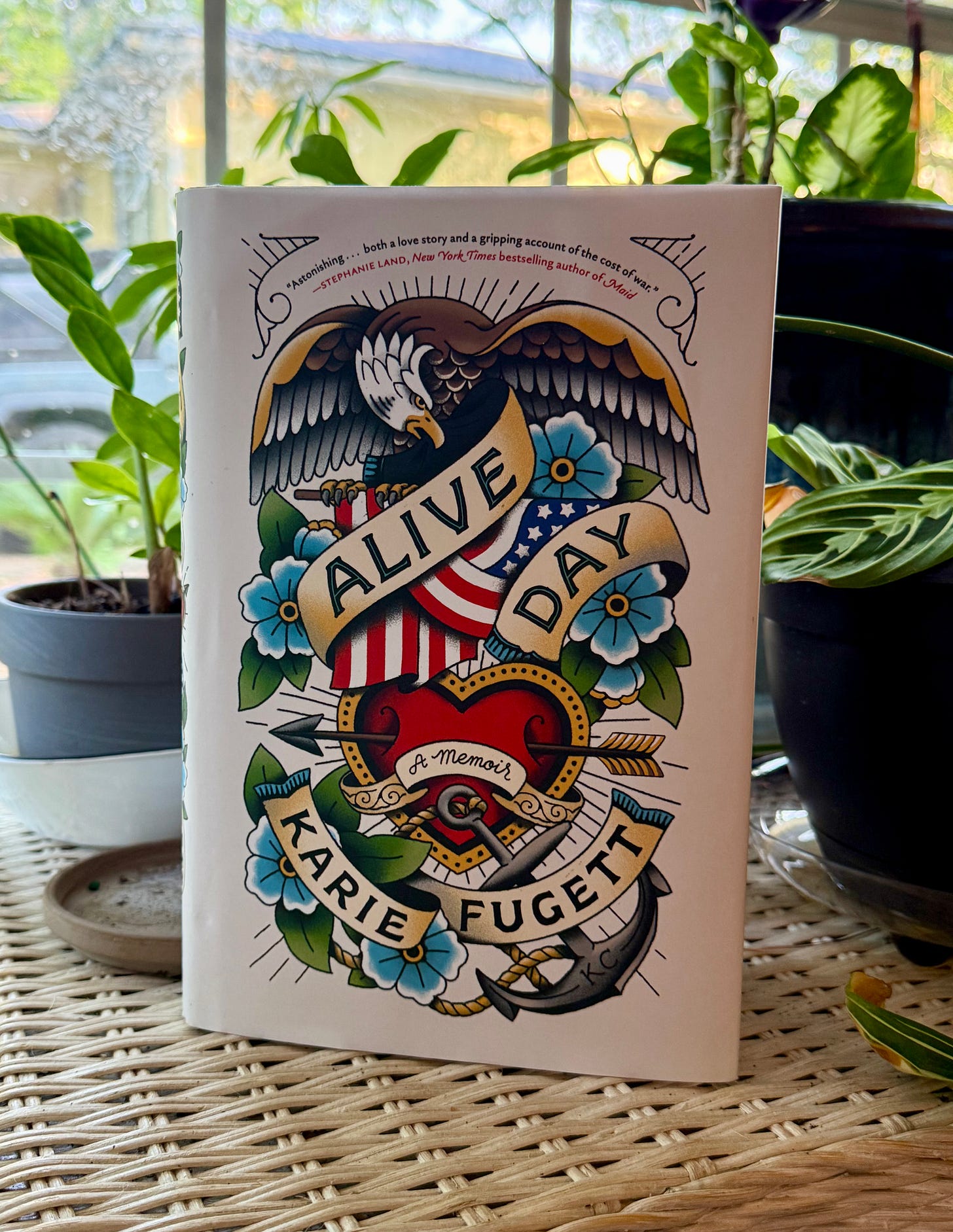

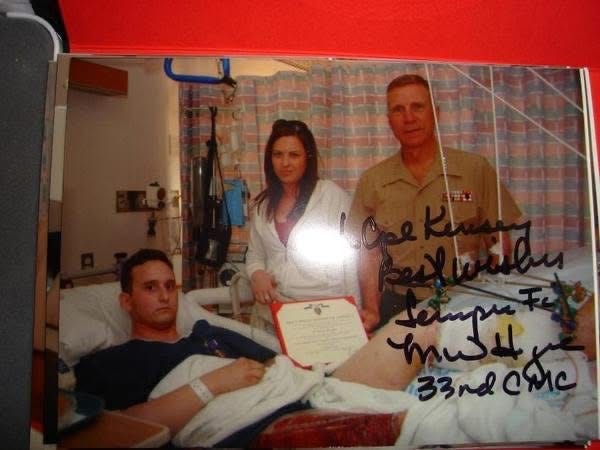

’s remarkable writing on war but once I did, I devoured everything she wrote. My parents grew up on London during WWII and, in turn, I grew up with war in my blood. Karie’s level-headed presentation of the cost of war not only on the soldiers but also the spouses, who all too often become caregivers, the family, friends, and the country went straight into the marrow of my bones. She told the truth — with empathy and eyes-wide-open clarity and gentleness and thoroughness and a longing for all of this war madness to change.Karie’s new memoir Alive Day is astoundingly beautiful. In it, Karie guides us through a childhood of abuse into a loving but complicated marriage to her grade-school sweetheart, Cleve, who joins the Marines and is soon enough deployed to Iraq. Within months, his Humvee is hit by an IED and Cleve is flown to Walter Reed with a serious leg injury. The doctors try to save it, putting Karie, barely in her twenties, in charge of some gruesome and grueling care but in the end, it needs to be amputated. Given pills for pain, Cleve quickly becomes addicted and Karie, realizing he’s also dulling PTSD, tries in vain to convince both doctors and loved ones he needs help. By twenty-four, Karie is a military widow.

Alive Day has garnered a starred review from Kirkus Reviews and was selected for Book of the Month. Karie’s work has been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Harper’s Bazaar, and more. She holds a BA in creative writing from the University of South Alabama and an MFA in creative nonfiction from Oregon State University. She lives in Alabama with her daughter.

It was such a pleasure to speak with Karie. I hope you enjoy our conversation!

xJane

⭐️ Karie is generously gifting three readers an autographed copy of Alive Day! If you’d like to be one of the recipients, please add “ALIVE” after your comment. The winners will be chosen at random on Monday, May 19th and notified by Substack Direct Chat. I’m excited for all of you! (Shipping is limited to the United States) ⭐️

Your book really drives home the fact that the majority of soldiers and their partners, who often end up as caregivers, are young: early twenties. You frequently refer to yourself and those around you as “just kids.” And you write: “I know now that Cleve’s death, and every casualty of any war is anticipated. Everything from widow stipends to prosthetic legs is part of a very large budget. And people like me and my husband—poor, uneducated, young—are chosen by recruiters who seek out the economically disadvantaged, knowing that those kids are more likely to enlist and stand on the front lines during wartime. Cleve and I were chosen, and we played our parts.” This is both heartbreaking and infuriating. Can you talk more about how it’s kids who are fighting our wars and kids who are acting as caretakers to the wounded soldiers who make it home and kids who are war widows and kids who are single parents?

When you look at how the military is structured, and you look at officers, those are usually people who have an education, which means they're probably a little bit older. The kids who are fresh out of high school, who don't have any college under their belt, they don't really have any skill set for the labor force—they end up the grunts, they're the infantry, which means they're going to be the ones on the ground in the thick of it if we're at war. Obviously, there are people of all ages that end up wounded and dying. But when we were in the hospital, the vast majority of the people who were there were our age—and we were twenty and twenty-one.

It’s mind boggling to think the age of enlistment in the military is seventeen! What's the age when our brains are fully formed?

Twenty-four. The year I was widowed. I thought about that a lot when I was writing the book, too. Because as it was all happening, I had a lot of guilt about the way I was handling some of the things in real time. I had a lot of anger. I was depressed. Acting out at certain times, and not living up to my values, if you will. So I really beat myself up about it.

Later, when I was revisiting all this stuff, I was thinking I was so young. Most of that happened before my brain was fully developed. Then the year that supposedly it was happening—I buried my husband. And that’s so common.

There was no rule book. I really didn't have much of a support system in the form of family. So I was just winging it. Things were coming at me—I was like, “I'm going to do this, and we'll see if that works.”

I finally made peace with knowing I handled everything the best that I could.

One of the other things that struck me was the way it was almost mandated that your life fold completely into Cleve’s and into the demands put on you by the military, especially when Cleve came home injured. You had to set aside your dreams to take on this role of caregiver, which carries so so so much responsibility. You write: “I understand now that the military relies on young spouses like me as cheap—sometimes free—labor. Military brass knows what to say to make young women think their labor is their duty.”

At that time, they weren't paying caregivers anything. A nonprofit would give us checks every once in a while to fill that gap. Eventually the military—I want to say a few years after that—finally got with the program and decided they should be paying these women for their labor. But at the beginning, the caregivers were guinea pigs.

How did you cope with that? I don't think they gave you any training or anything, right? They didn't say, “this is how you care for your seriously injured husband.”

They handed me a pamphlet at one point about PTSD. A general like, “Look out for these things,” but it was under the context of his care. It wasn't talking about how it could affect me. Later in the book one of the nurses says, “Oh, you could have secondary PTSD.” Looking back I think I just had PTSD. But secondary PTSD is a thing. It’s caregiver burnout. A lot of caregivers do experience that. They weren’t talking about it beforehand.

I was being told this is my responsibility to take care of him, these are the things that we want you to do. I felt overwhelmed by it, it felt like failing. I had no understanding of what was going on with me mentally, emotionally, and psychologically. Now I have a much better understanding of things like PTSD, depression, anxiety, because I’ve done the research and had therapy. Back then it was just like, “there's something wrong with me. I should be stronger than this.” It’s a lot of whipping yourself.

Your body must have been in overdrive, because you were in a state of constant worry, constant hyper-vigilance. Were you sleeping? Were you able to rest? Were you able to calm and care for yourself? Or were you focused on Cleve all the time?

Because of the way I grew up, I was used to being in a hyper-vigilant state. So in some ways it was perfect for me, because I almost thrive on that high that you get when there's an emergency. I say thrive... it feels like I'm thriving, but it's really spending every ounce of energy at once and then feeling very exhausted later. But when there's an emergency, I'm like, “okay, this is what we need to do.” I go into action mode. So I was depending on that a lot.

I was depending on a lot of unhealthy coping mechanisms, like overeating. I was drinking too much. I took Cleve’s pills every once in a while. And I poured myself into this idea that my purpose was to be his caregiver, and even if I burnt myself completely out doing it, it was worth it.

There was a point I was on sleeping pills because I was starting to have nightmares and staying up at night. Cleve had sleep apnea due to some of his injuries so he snored really loud and would wake up kicking the air with weird dreams. So I was not sleeping very well. And I was eating a lot of junk food. Smoking a lot of cigarettes.

Do you have different care mechanisms now?

I do. How good I am at practicing them depends on how things are going on in my life. Working out regularly is huge. Meditation can be huge, even though it’s difficult for me to get into that. When I do it daily, it’s almost miraculous how much of a change I see with my anxiety. Talk therapy.

I'm on medication now, which is something that I avoided for a long time. I didn’t start until my daughter was born. She’s four now. I’d convinced myself that I wasn’t truly better or healthy if I had to take meds. Like, I needed to figure it out some other way.

But I was a roller coaster. I would have a period of time where I was doing pretty well, and then I would get overwhelmed and fall back into those bad habits that I mentioned. Medication doesn’t solve everything. Having healthy practices in your daily life is also important. But it made me realize how high-strung I had been. I didn’t truly realize how bad my anxiety was until I took a med. I was like, “oh, this is really nice.”

You slowly discover you’re carrying your own trauma from things that pre-date your marriage but also the experiences of being married to first an active and then seriously injured soldier. You write, “I didn’t want people to think I was taking attention away from Cleve. He was the one who had gone to war. Anything I was going through, comparatively, felt silly. I wonder now what about my PTSD was “secondary.”” Can you talk about your journey toward understanding you were also dealing with trauma?

It took me way too long. Especially considering all the therapists I’d talked to along the way. I was thirty, maybe. When I was taking care of Cleve, I didn’t know much about mental illness. The whole time that I was taking care of my husband, I thought you had to have been at war in order to have PTSD. That was black and white in my mind back then.

When that nurse told me about secondary PTSD, that was the first time I’d ever heard that. It was the first time I’d considered that it could be affecting me too. I did feel very guilty about thinking about accepting that because it felt like I was taking away from what the focus should have been, which was taking care of the war-wounded hero

It was when I was getting a college education and taking sociology, psychology, and having conversations with other people who knew more than me, that I realized maybe I should do more research on this.

Then it hit me, like, I might have been traumatized at six. I’ve been carrying this a long time. After that, a lot of things started to click into place, and that’s when my journey to forgiving myself started. If the trauma for me started at six years old and no one ever told me how to deal with that, I always figured it out on my own, how could I blame myself?

Not to say that I don’t take responsibility for my actions, obviously I do. But I’m able to be a little softer with myself and not be hard on myself for the things that I did, that I don’t love.

Is there a formal practice you have for that?

Writing was huge. I know it’s cliché to talk about memoir and healing. But it is healing. For me anyway. Being able to look at myself in the past and think about that version of me in the form of a character in a book, it turned me into more of a separate being. I was able to look at what was going on a little more objectively, instead of feeling like it was all part of me.

At first, I was like, “I did that. It’s my fault.” But when I looked at myself as this younger person who’d experienced these things, I was like, “This is just a human being trying to figure it out, who went through a bunch of things that she didn’t know how to handle. That person deserves forgiveness.”

When Cleve came back, you got lots of physical medical support but there was nothing offered for mental health. Why do you think, the moment the soldiers are back, the military isn’t immediately providing mental health support for them and their spouses?

They’ve improved a lot over the last ten to fifteen years, especially in those areas like opioids, mental health care, taking PTSD seriously, taking traumatic brain injury seriously. It took people dying, and people talking about it in the news, and people getting angry for them to finally start addressing these things.

Early on, maybe they weren't fully aware. But then I'm like, “this isn't your first war, military.” I don't know how much credit I want to give them.

Do you think it would have made a difference when Cleve came back if there had been readily available mental health care support for the two of you?

Yes! If they were like, “Okay, you get a therapist. And you're going to be on pain meds for a long time so we need to have someone monitoring your usage.” If right out of the gate, I’d had some training to not take his outbursts so personally. I took everything personally, like it was my fault, and that weighed me down pretty quickly. And him, too.

Cleve becomes addicted to pain killers. Doctors told you it was unethical to take him off pain meds altogether. Yet he was clearly taking too many and showing myriad signs of addiction. You often had to fight against what Cleve and the doctors were telling you and listen to your own voice, a voice that had been shut down, that knew Cleve was addicted. What was the process like of learning to trust yourself and your knowings more deeply?

It is really hard, especially when you're dealing with a system like the military that's so big and powerful. They control everything from your paycheck to where you live. It's intimidating. If they're suggesting that one thing is the truth, and continuing to say that, then you start to question yourself. Especially at that age. I’d been around drugs some, but I didn't know what the difference was between addiction and someone who has an infected leg, or the difference between symptoms of addiction and PTSD. A lot of those symptoms are overlapping.

At that young age, being in such a powerful system with all of these people telling me that it's fine, even though my gut knew that something wasn't right, I did not have the self-confidence to assert my truth. I wanted to prove that I was a good caregiver, that I was doing my job well.

I would imagine, it must have been all men you were going up against.

Yes. A few female nurses. But even most of the nurses were men. I did not have any tools for that at all. I did mention my concerns during one of Cleve’s appointments, and was brushed off. I was like, “Okay, maybe I am overreacting.”

Then I would notice things him passing out and his cigarette singeing holes into his pants. And I'm like, “I don't think this is normal.” So I would mention it again, but it kept getting pushed to the side. And again, I didn't have the confidence to march in there and be like, “Fucking do something.”

I don't know how you held it together as much as you did. Because you moved so often growing up, it was difficult for you to form lasting friendships and you often felt alone. Based upon the friendships you depict in this book and your abundant acknowledgements, it seems that’s no longer the case. What role does friendship play in your life?

Huge, huge role in my healing process. When I was younger I thought that people didn't like me. In retrospect, I realize I didn't like myself very much, so I couldn't understand how someone would like me, and that affected the way I interacted with people. I was afraid to talk to people. I was afraid to be myself. I was awkward. I was angry. I was all these things that no one wants to be around.

If I’d not worried so much about whether people liked me, I would have had plenty of friends. I know that is because once I got older and went to college, I wasn't as worried about people liking me, and whether I was weird, and immediately I was like, “Oh, my gosh! People want to talk to me!” I was attracting people that understood me, that were similar to me, and it became almost easy. I think the key is, you have to like yourself.

At first you hate the men who hurt Cleve and want them dead. But over time, you find yourself wondering what their names are, if they have families, what their lives are like. And how many of their loved ones have been hurt or killed. What impact did this humanizing of the enemy have on how you see the world? And how you see yourself?

It's morphed over the years. Back then, I was ignorant about a lot of things, and if I saw something on the news, my parents watched Fox, I assumed it was fact. Certain people were called terrorists and were dehumanized. To me, it was, “they’re trying to kill us, and they're the bad guys.” And that's it.

I didn't really think it through until I had this wounded husband. Once I was in the hospital with Cleve, and getting a little older, and had way too much time to myself, I started thinking about it. And I was like, “there are two sides to this. People are dying over there too.” At the time I didn’t realize how many.

Even then, though, I was just starting to really consider our role in this war. [Karie tears up] Sorry, this actually makes me emotional. The older I get, the more upset I get about the effect it had on Iraq and the civilians there. There was a point where I was writing this book and was like, “I can’t write this anymore. Why does this point of view even matter when we caused that amount of suffering over there?” It’s taken a lot of therapy.

When Cleve was in the hospital, that’s when I started to do more research about who is fighting these wars for us. Who does war benefit? Why are we going to war? What’s the point of doing this? I realized that there are really rich people who make a lot of money off it and those people pay our politicians to make choices in their favor, including going to war. They send recruiters to poor communities like mine, where they know these kids don’t have other opportunities, or they send them to military bases because they know these kids are around the military already and are more likely to join. That’s the strategy behind it. I realized that it's worthy of talking about even if I'm still upset about our role.

I’m glad you are talking about it, Karie. So much is hard right now, where are you finding joy?

It's usually simple things. My boyfriend and I have this little reading club between us.

Oh, I love that.

It's almost always things like sci-fi, or not too serious. Doing that before bed every night is nice. Spending time with people who are important to me, especially ones where I don’t have to worry about looking a certain way, speaking a certain way, and I can totally be myself. Lots of laughing.

Getting outside. Today is beautiful. I had the door open and the air off, and let some sunshine and fresh air come in. And remembering that even when things are hard, there is always something beautiful out there that you could be focusing on. And it's okay to enjoy that, too.

⭐️⭐️Beyond is a reader-supported publication that pays contributors. Thank you to everyone who’s joined this beautiful, growing community devoted to bringing as much light as possible into this world of ours. If you would like to support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Beyond cannot exist without you! ⭐️⭐️

If you enjoyed this interview with Karie, you might also enjoy this one with

:

Really thought provoking interview. Thank you very much.

ALIVE

Thank you for sharing your story, Karie