Vanessa Chakour On Rewilding Through Boxing

Cultivating internal strength through training allowed Vanessa to heal from trauma, become more present to the heartbreak of the Earth, and advocate for our misunderstood and mistreated wild relatives

What first drew me to

was her deep love of animals and the land and her social activism of their behalf. She so beautifully weaves together holistic herbalism and therapeutic arts and passionately advocates for wolves and so-called weeds who cannot speak for themselves. She reminds us that we are nature — not something separate from it. She’s written two gorgeous books: her memoir, Awakening Artemis, which tracks her journey of healing through the lens of twenty-four medicinal plants. And the recently published Earthly Bodies: Embracing Animal Nature which explores inner and outer landscapes through the lens of wild animals. She also writes the Substack which encourages us to trust our intuition in order to deepen our connection to the wild and to ourselves. As you all know, these topics are near and dear to my heart!So it was an extra delight to discover that Vanessa is also a boxer. Boxing has played such a vibrant and pivotal role in my life. I began over two decades ago when I was nine months into debilitating, nonstop head pain from head and brain injury. The root of the pain, my jammed occiput, was so severe doctors told me these were nicknamed “suicide headaches.” It may sound odd that I decided to box in such staggering pain but many doctors were telling me I would always be in this level of pain and although I believed I could get well, I needed an outlet for all the fear and anxiety that was coursing through my body. Plus, my intuition was guiding me there. I couldn’t spar, of course, but I could hit the bag and pads — and I luckily ended up with two highly skilled coaches, one of whom told me if I weren’t in my thirties with a head injury, he’d be training me for the Golden Gloves. I was good and I loved it. And within three months, the pain was gone. I was doing many other things for the pain, so it’s impossible to know what role the boxing played but I believe it helped tremendously. In varying ways, boxing is still in my life.

Vanessa has written the most captivating essay about her journey with boxing and how it has impacted, well, everything (it also helped with her healing!) including her nature advocacy. I loved reading this. I was so inspired! I think you will be, too!

If you want to learn more about Vanessa and her beautiful work, she filled in the Beyond Questionnaire earlier this year!

⭐️ Vanessa is generously gifting three readers an autographed copy of Earthly Bodies! If you’d like to be one of the recipients, please add “EARTHLY” after your comment. The winners will be chosen at random on Monday, October 7th and notified by email. I’m excited for all of you! (Shipping is limited to the United States) ⭐️

Rewilding Through Boxing

I didn't realize how much I’d missed boxing until I started coaching again at the local YMCA this summer. I've often omitted the decade and a half I spent in the sport from my public persona, as it seems to create a cognitive dissonance with my primary focus on writing, land stewardship, and nature advocacy. People tend to assume that as an herbalist, instead of hitting a heavy bag, I should just be skipping through flower beds (which I also do, of course). We compartmentalize ourselves in this strange world of "branding," but the reality is, we are all multifaceted.

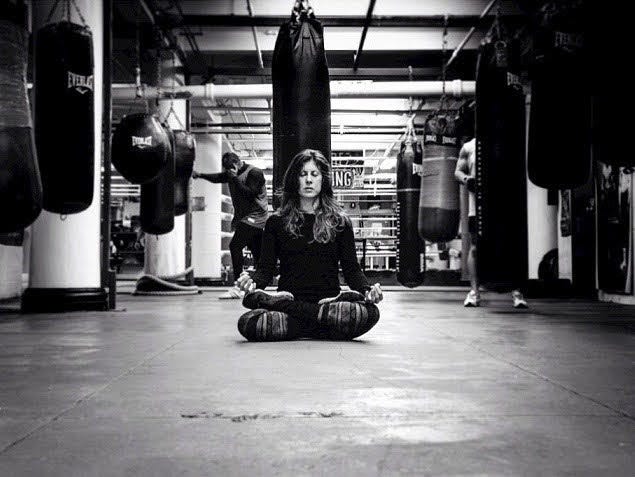

Rewilding, a term often applied to ecological restoration, is equally relevant to the human experience. A discipline that demands a profound connection to one's body, an acute awareness of space, and an unwavering focus, boxing has been essential in reclaiming my body and in my process of rewilding. Women all too often have been told to tone down, be nice, be pretty, and smile. In the ring, stripped of these societal constraints, I accessed primal instincts that reside within us all. This awakening of my physicality became the foundation upon which I would build a deeper relationship with the natural world. Boxing is entirely connected to my land-based activism. It awakened my animal nature. We humans are animals, whether we admit it or not.

Rewilding

I remember riding the subway from Tribeca to Brooklyn with an ice pack on my face in 1998 after my first sparring session. I was twenty-five and nursing a bloody nose with a serious shiner on its way, I noticed people staring at me with horrified expressions. I wasn’t as skilled as I thought I was. My face and my ego bruised in the aftermath, I hid in my apartment as much as I could. It took a few weeks to take care of my physical wounds and, though my confidence was shaky, I eventually got back in the gym, laced up my gloves, opened wide for my mouth guard, and stepped into the ring again. I was possessed by a need to become strong, a skilled fighter, and yearned to trust myself in the ring; a place where my opponent trained to expose and exploit my weaknesses. In a world where women are considered the “weaker” sex, conditioned to shrink, and told beauty is our currency, boxing was my little rebellion. I wanted to know the part of myself that was predator instead of prey.

Until I began boxing at age twenty-three, I had an incredibly fraught relationship with my body. In one of my long-standing inner narratives, I had the starring role as the asthmatic girl sitting on the sidelines, incapable of participating in gym class. Growing up, I felt like there was a spotlight on me showing everyone I was incapable. When my elementary school gym teacher insisted I run around the perimeter of our elementary school for the annual fitness test like everyone else, I had an asthma attack that landed me in the hospital. It was absolutely humiliating.

As a teenager, I was forced to have sex without consent and left my body behind. I dissociated, played dead, and don’t remember putting up much of a fight. Afterward, memories of earlier abuse started to emerge. I felt out of control of my body and hated what she seemed to attract, so I began to rein her in by fighting hunger. My incredible restraint, denial of food—a biological imperative and pleasure I once loved so much — helped me hold disturbing memories at bay, numbed my emotions, and made me feel strong. If I could move beyond hunger, I reasoned, I had total control of my body, and that was power.

Then, at sixteen, a car accident changed the course of my life. My back and neck shattered, and I was trapped inside my bedroom and body for months. Enclosed in a fiberglass brace, I moved slowly, and tenderly. Dependent on others for my most basic needs, I had no choice but to eat. I could no longer hide my eating disorder and survival became my full time job. I dropped out of high school to heal. As I began an excruciatingly slow process of recovery — healing my body through physical therapy, and processing mental and emotional trauma through writing, visual art and psychotherapy, I began to land back in a body I’d been trying to transcend. We can describe how we feel in the most vivid detail, but in the end, we must traverse our inner landscapes alone.

In Waking the Tiger, trauma therapist Dr. Peter Levine talks about moving as an essential way to release embodied trauma. We literally have to get it out of our system. When threatened or injured, all animals draw from instinctive reactions to protect and defend oneself such as freezing, stiffening, bracing, fleeing, collapsing, or fighting. In the wild, animals recover from trauma by shaking spasms of their body core, along with flailing limbs to complete the fight-flight they were in before they froze. But our human-mind often interrupts this natural reset after a traumatic experience. Whether we’re fearful of the impulse to shake our bodies or the flood of our normal animal-aggressions, we often ‘hold it together’ and keep our composure. This, according to Dr. Levine, is why humans hold onto trauma and wild animals (those not in captivity) usually don’t.

When I think about the way I dealt with sexual assault when I was young—freezing, leaving my body, and playing dead—it makes sense that I had to move in such an intense and extreme way to get it out later. “The restoration of healthy aggression,” Levine writes, “is an essential part in the recovery from trauma.”

It would take over a year of rehabilitation before I could move in the unbridled way my body yearned to. The moment my bones were ready, I began strength and cardiovascular training at the local fitness club. Though my respiratory system was still a challenge, I was learning to manage it. I had initial wheezing, but if I took my inhaler or even took a few minutes to relax my breathing after the onset of asthma, it would subside. And when it passed, I discovered incredible endurance. Eager to push further, I found books on sports psychology where I was introduced to meditation and visualization. When I felt like I was hitting a wall, I visualized a golden light illuminating and animating my body, giving me newfound energy. I practiced visualization outside of training and imagined myself running further and faster each day in as much sensory detail as possible: I felt the earth beneath my feet, the air and wind against my body, heard my sneakers touch the ground, and imagined my breath unobstructed and deep. The young me sitting on the sidelines, finally came down off those humiliating bleachers.

The Urban Wild

I moved to New York City on a whim in the mid-nineties. I was twenty-two years old and had an opportunity to assist a well-known photographer. I figured I should experience the city and make connections while I was young, then pursue my dreams of living in the wild and working for National Geographic. Scrambling to make ends meet. I was always on the hunt for something financially sustainable so soon I became a personal trainer. It made sense, I’d learned a lot from the car accident rehabilitation, had become strong and worked hard to dismantle my stories of the physically deficient asthmatic-kid and the woman who needed to shrink.

One day at the gym, I met a professional boxer and was captivated by the beauty and power of shadowboxing. Growing up in a family of artists and physicians, boxing was never on my radar, but the fluidity and grace of the movements immediately drew me in. That summer, that same fighter offered a boxing-fitness certification for trainers. The idea that you can learn such a complex skill, or even learn to hold focus mitts (small, padded targets used to improve hand-eye coordination, reflexes, and punching accuracy) in a short course is total bullshit, but the prospect of boxing excited me. When he guided us through drills and taught us how to throw a real punch, I felt a strange and deep sense of relief. It was as if my body had been waiting for this moment, desperate to unleash her power. I knew I was just scratching the surface and needed to explore more.

I convinced the boxer to train me. Although he trained me only once or twice a week, I practiced regularly on my own and began a daily ritual of reclaiming my body. I pounded the heavy bags until my knuckles were raw, spent endless meditative hours on the speedbag, and after tripping over my feet for months, became proficient on the speed rope. Each day of training, I was soaked in the bittersweet sweat of anger, grief, and fear that I hadn't even known was lodged inside. It was as though I had just swum, fully clothed in the ocean, and every time I peeled those sopping clothes off and carried my heavy, waterlogged bag home on the subway, I felt a little more free. Ravenous afterward, I stopped counting calories and learned to heed my hunger.

After training for about six months, a fighter and his coach came in for sparring, which was a rare event at my training location. Although the gym had a ring, it was primarily used for boxing fitness, not fighting. I’d been in the ring to practice footwork and focus mitts with my coach, but never for sparring. When the fighter's sparring partner didn't show up and I was hitting the bags nearby, they asked if I wanted to get in the ring and throw punches at him. They assured me it would be a one-way fight; he just needed to work on his defense. I was nervous but agreed, eager to test my skills against a real opponent.

As I stepped into the ring wearing a pair of heavy 16-ounce sparring gloves, a surge of adrenaline coursed through me. When the bell rang, my heart pounded and I attacked with everything I had. Unleashing a flurry of punches, it was a side of myself I'd never met before. My opponent, a seasoned fighter, looked a little shocked, although he dodged and countered most of my attacks. I kept pressing forward, determined to prove myself.

After several rounds, I could no longer keep my hands up, my legs were on fire, and my breath was reduced to ragged gasps. When I had nothing left after five rounds, they nodded respectfully, helped me unlace my gloves and told me I should consider training to fight. I knew they were right. It was time to go to a real boxing gym and get a more consistent, committed coach.

Months of intense and sometimes demoralizing tours of potential coaches and boxing gyms in New York City, like the one in Tribeca whose tests of my ability and heart resulted in black eyes and bloody noses, eventually led me to Gleason's Gym in Brooklyn, which became my home away from home. I remember the first day I walked up the stairs and into the famous, grimy boxing gym in 2000. No music, just the sound of boxers hitting heavy bags, speed ropes hitting the floor, trainers yelling at their fighters, and the intense, overwhelming smell of sweat. Everyone trained, sparred and shadowboxed to the same three-minute bell, resting during the same one-minute period. That ebb and flow of energy became a living, breathing organism all its own, and it was impossible not to get caught up in the intensity. One of my favorite things about boxing gyms like Gleason’s is that a beginner might train alongside a world champion any day she walks in. When boxers were preparing for fights at Madison Square Garden, they came in for sparring. Several world champions would train alongside me daily.

But on my first day training at Gleason’s, I walked up the stairs to the ring and climbed between the ropes with what felt like all eyes on me. My coach told me to climb up into the ring and shadowbox. I was on stage and I felt like a fool. The asthmatic girl who had never had a fight in her life and whose defense mechanism under threat was to freeze was fighting an invisible opponent in one of the most famous boxing gyms on earth. The first few rounds were exhausting. I was trying way too hard. But after a while, people lost interest in me and I forgot that I was performing. I burned off my nervous energy and entered my own world. I was in a groove, in sync with my body.

In sparring or in a fight, there's no time to second-guess your decisions or dwell on past mistakes. This was a great teaching for me as an overthinker and over-analyzer. There were countless times in the past when my instinct told me to act, speak up, speak out, but I didn't or couldn't. Through boxing, I learned to trust my instinct and act, and eventually, inspired others to do the same. When I developed enough skill, I turned pro, coached boxing, and taught other women how to fight.

Animal Nature

I would support myself by coaching boxing and facilitating nature-connection in the urban wild for over a decade. The same wildness I found in boxing is essential for ethical wildcrafting. The skill requires reverence for nature, and like reading an opponent in the ring, the ability to read the land and her inhabitants. I often said that herbalism felt like a bone-deep remembering. It's like rediscovering a forgotten language, a genetic memory that connects me to my multi-species family. Something I already knew, that needed to be awakened.

Similarly, within each of us, there is a natural framework for fighting; it's something we were all born to be able to do. And the more I've cultivated internal strength through training, the more I've been able to embrace my vulnerability, allowing me to let down my guard and feel more, not steel myself against the heartbreak of Earth. As someone who is intensely porous and loves the earth, my local ecosystems, and misunderstood and mistreated wild relatives like wolves, coyotes, dandelions, and bats so deeply that it's sometimes unbearable, this inner strength is essential. As I grow stronger on the inside, I need less of an outer shell.

"From the ground up," my coach always said, "All your power comes from the ground up." Like weeds that burst through the cracks in the sidewalk, it's the roots, the life-force energy of Earth that push the plant through boundaries to break free.

I find it helpful to remember that beneath all the layers of domestication, we carry the wild within.

If you enjoyed this essay by Vanessa, you might also like this one by Gayle Brandeis:

⭐️ Beyond is a reader-supported publication with the goal of bringing as much light as possible into this world of ours. If you value my work and would like to support it, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

Exceptional. Thank you. I was linked to this via another post on "The Perfect Couple" by Amy.

Glad I was. My mother of 8 to an abusive husband and Church back in the day (early 60's) REWILDED herself through Judo. It gave her the strength and courage to bounce my father out and take back the house. It's a memory i will never forget — of course there is a longer version.

The author was wild enough to choose her unlikely, unique path to healing. What a warrior! GIF Bless