Nicole Graev Lipson on The Tenderness of Truth

How writing a memoir unexpectedly brought Nicole closer to those she loves

Nicole Graev Lipson first came into my orbit through our very own

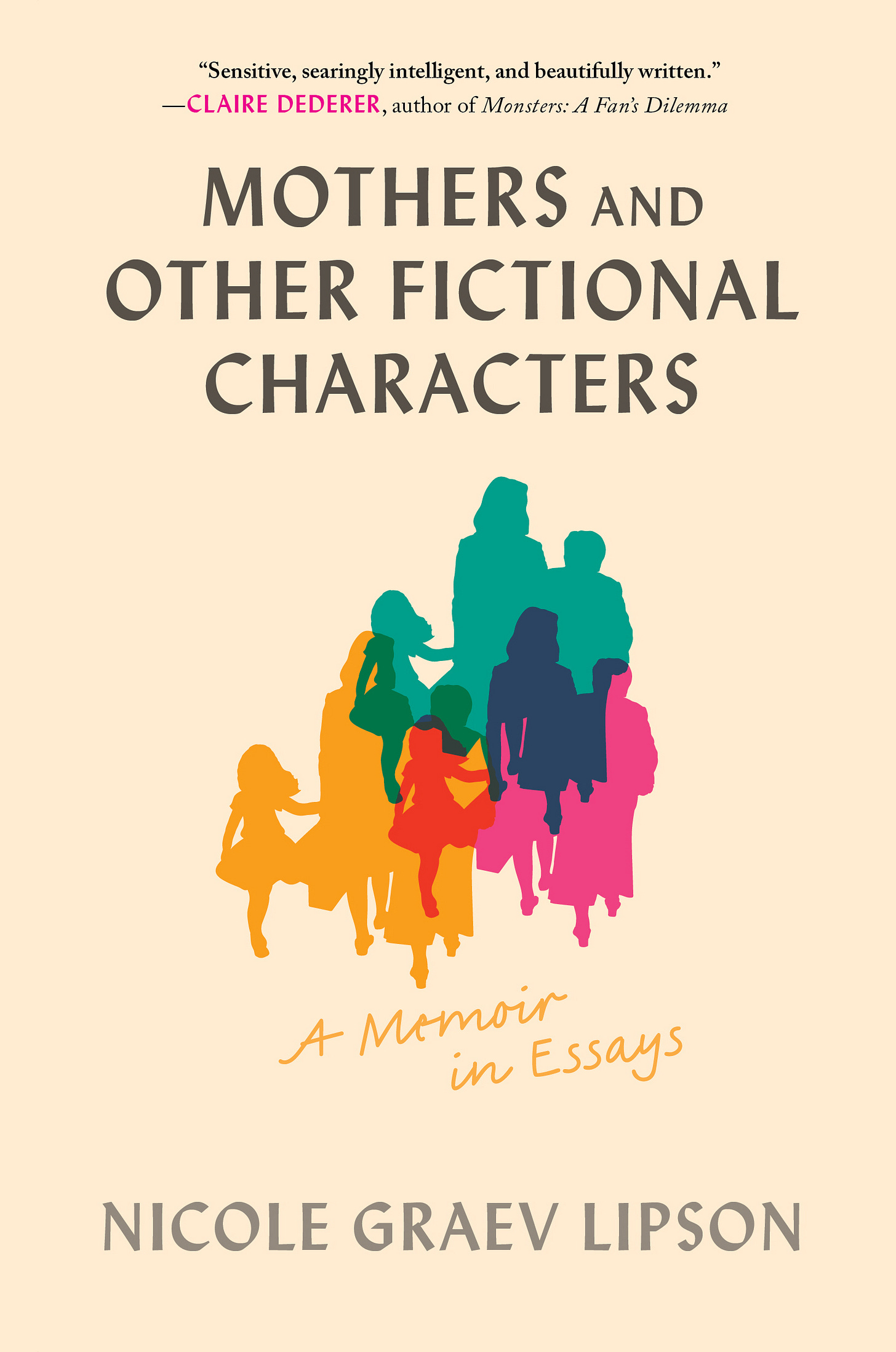

who writes the brilliant monthly column for Beyond. We started chatting and it turned out Nicole had a memoir in essays coming out in March with the compelling title, Mothers and Other Fictional Characters. Kirkus Reviews gave it the rare and coveted star and it landed on The Millions list of Most Anticipated Books of Winter 2025 and Zibby Owens’ list of Most Anticipated Books of 2025, amongst others.The book explores what it takes to escape the plotlines mapped onto us. Searching for clues in the work of her literary foremothers, Nicole untangles what it means to be a girl, a woman, a lover, a partner, a daughter, and a mother in a world all too ready to reduce us to stock characters.

I’m so delighted Nicole agreed to write an essay for all of us. So often the stories of memoirs tearing apart families or friendships make the news. But Nicole delves into what happens when the opposite it true: when a memoir draws loved ones closer together. This essay brought me great joy! I think you’ll feel the same!

Originally from New York City, Nicole lives outside of Boston with her husband and three children.

⭐️ Nicole is generously gifting three readers an autographed copy of My Mother and Other Fictional Characters! If you’d like to be one of the recipients, please add “MOTHER” after your comment. The winners will be chosen at random on Monday, March 17th and notified by Substack Direct Chat. I’m excited for all of you! (Shipping is limited to the United States) ⭐️

The Tenderness of Truth

As my debut memoir Mothers and Other Fictional Characters neared its recent publication, I did what I always do when I’m nervous: made lists. One of these was a list of questions bookstore audiences might ask me during Q&A sessions. These were harder than I anticipated to predict, but there was one question I was absolutely certain I’d be asked, because it’s the question every memoirist gets asked: How do your loved ones feel about being in the book?

Readers aren’t the only ones who love this question. Wherever we nonfiction writers gather—in workshops, or by the bar during writing conference happy hours—we, too, eventually get to the topic of writing about the people in our lives. Comparing our approaches and philosophies is a form of “shop talk.” I’m sure there are memoirists out there who forge boldly ahead in the work of writing about real people, consequences be damned: “If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better,” Anne Lamott has famously said. But personally, I’ve never met one. The memoirists I know have all, like me, spent untold hours groping their way to the ethical parameters that feel right to them, and they all long to write about others with sensitivity and care.

I’ve always been fascinated by the complexities of relationships and the dramas below the surface of daily life. And so, unsurprisingly, there are many loved ones in my book, including my husband, my three children, my parents, and my dearest friends. One rule of thumb I’ve followed when depicting these loved ones is to write, always, from my own perspective and embodied experience. I cannot know what my children or my husband see and feel and think as they move through the world, and their stories aren’t mine to claim. I can only know what I see and feel and think: the lived sensations that comprise the tale that is mine.

There’s another principle that guides what I write about loved ones—one that I have my daughter’s second grade teacher to thank for. She encouraged her students to ask themselves four questions before speaking, summarized by the acronym THiNK: Is what I’m saying True? Is it Helpful? Is it Necessary? And is it Kind? Reading my daughter’s handout about this framework was a revelation. It captured so beautifully what communication can be at its most honest and humane. It wasn’t just a surface politeness Ms. Smith was encouraging, but a mode of empathy. What a gentler, safer place the world would be, I thought to myself, if not just seven-year-olds but all of us—parents and spouses and co-workers and politicians—put our words to this test before uttering them out loud.

The THiNK test has become a part of our family’s lexicon: all three of my kids know exactly what I mean when I remind them, mid-sentence, to use it. And it has become central to my writing and revising process: there isn’t a paragraph in Mothers and Other Fictional Characters that I haven’t weighed against its standards. To me, writing with the THiNK test in mind isn’t the same as being diplomatic. It doesn’t mean flattering my subjects, or sugar-coating what is painful, or tidying what is messy, or glossing over what is hard. But it does mean sharing only those details of my life with my family that are vital to a story’s telling and helpful, in a broad sense, to the reader. And it does mean writing with a regard for the dignity and humanity of the flesh-and-blood people who live in my words.

I’ve spent so many hours pondering the ethics of writing about loved ones—and developing an approach that sits comfortably with my conscience—that I could write a whole craft book on the topic. And yet…and yet. When I imagine someone asking, “How do your loved ones feel about being in the book?” I still feel dread. Perhaps this is because embedded in this question, however gently it’s asked, is the assumption that one is doing something unsavory when she writes about her loved ones—violating their privacy, betraying their trust, exploiting their lives for material. It doesn’t feel good to be accused of wrongdoing, however subtly. And personally—likely due to my female-conditioned longing for approval—when I’m accused of doing something wrong, I strangely feel like I’ve done something wrong, as if the suggestion itself has made me culpable.

Are there memoirists who have crossed a bright red line, violating their family’s privacy out of revenge or spite. There are. But over the past few years, I’ve come to question the knee-jerk assumption that writing about our family and children is inherently negative. The museums of this world are filled with portraits of wives and lovers and children by celebrated artists. When we gaze upon Monet’s Portrait of Michel in a Pompom Hat, or Matisse’s Portrait de Marguerite, or Rembrandt’s Titus, the Artist’s Son, we don’t wring our hands and tsk tsk at the ethics of these masters. We soak in their work, lingering on every detail: the pale gray hue of the eyes, the flecks of light in the hair, the shadowed folds of the clothes. We inhabit, for a moment, the artist’s loving eye, recognizing in every brushstroke his regard for his subject. The poet Mary Oliver said that “attention is the beginning of devotion,” and portraits like these encapsulate this truth. They insist that the human before us is important, their spirit and being worthy of contemplation.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these morally blameless artists were all male, and the morally suspect genre of memoir is often tagged as female. One day, I will write an essay about artistic judgment and gender. But for now, I will stick to the personal and say only that writing a book about the people I love most did not ignite tensions or drive a wedge between us. In fact, it had the opposite effect. Talking with my husband, children, and parents in real time about what I was writing, and sharing with them the passages in which they appear, cracked open the door to some of the most honest and loving conversations I’ve had in my life. Because of my memoir, my son now knows how desperately I long to protect him from male expectations. Because of my memoir, my mother and I have bonded over our shared maternal shames and struggles. Because of my memoir, my husband and I understand each other’s desires like never before. What people long for most, these conversations have made me realize, isn't to be seen as perfect, but to be seen and understood in all their murky complexities and loved nonetheless. I know of nothing that can get at the “both/and-ness” of loving like literature. As a writer—and human—my words are my attentive brushstrokes, my sentences the winding pathways of my devotion.

How do your loved ones feel about being in the book? When I am asked this, I think what will say is that I cannot speak for my loved ones. Only they know what it is they feel inside. My job, and my only job, is to tell my side of the story—truthfully, helpfully, selectively, and kindly— allowing them space for their vast, unfathomable depths.

If you enjoyed this essay by Nicole, you might also like this one by

:

Jane, thank you so much for introducing me to Nicole's essay collection, and for featuring her thoughtful commentary about the ethics of including others in our memoir.

Nicole, this was so helpful to me. I have a polished draft of my own memoir manuscript (about my motherhood being shaped by my religious upbringing and then shattered by the birth of my daughter who was born with a rare genetic condition), so I have grappled with this issue many times. I have heard several NF writers speak of this in different ways, and the one piece of advice that struck me the most was this: Have a conversation with the people who show up in your book before it's published.

I know this can be tricky for many reasons, and for some it simply cannot be an option (in the case of abuse, for example). I think I can navigate it, though, especially with the more tenuous relationships, like between me and my mom. What I chose to do was write the book uncensored and continue to revise without censorship, and once my book is (hopefully) picked up by a publisher, then I will have that conversation with my mom to allow her to see what is being made public about our relationship. That doesn't mean I will change the truth, because as you said, I cannot speculate about what she felt or her motivations. I can imagine. I can write about the impact of her behavior on me. And I have.

It's complicated, but you did a beautiful job of explaining how this can be done. And you offered me a boost of hope. Thank you!

MOTHER

Nicole, thank you for sharing this wonderfully written essay. Memoirs have long been one of my favorite reads, and I will be adding yours to my list of books to read. When I delve into a memoir I feel like I am transported into the author’s life and walking beside them through the stories written. MOTHER