Make Art in the Face of Fuck: A Conversation with Lidia Yuknavitch

On talking to trees, narrative transmogrify, releasing old stories from our bodies, standing in community, art as resistance, and joy in the tiniest moments.

Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

Lidia Yuknavitch is one of my favorite people to interview because she’s astoundingly brilliant with an enormous imagination so her mind reaches into corners of the universe most of us didn’t even know were there. She loves animals in that full-throttle sort of way a child might, she loves the whole planet that way. She’s kind and funny and generous and will talk about anything with such tender openness my heart swells. She wants all of us to thrive.

Lidia is also one of my most difficult interviews because when I speak with her, I want to ask her about everything and I do mean everything—love, grief, frogs, rage, sex, 265-foot cranes, trauma, swimming, disability, hope, art, death, politics, violence, trees, painting, monsters, healing, addiction, kindness, community, surviving all that this world throws our way. This is because she writes about everything. And I do mean everything. A scene might appear to be about Lidia’s profound love of swimming but it’s really about loss, empowerment, helping one another heal, and the interconnectedness of the world. And so I must whittle my 5,724 questions down to a more manageable amount. Not easy.

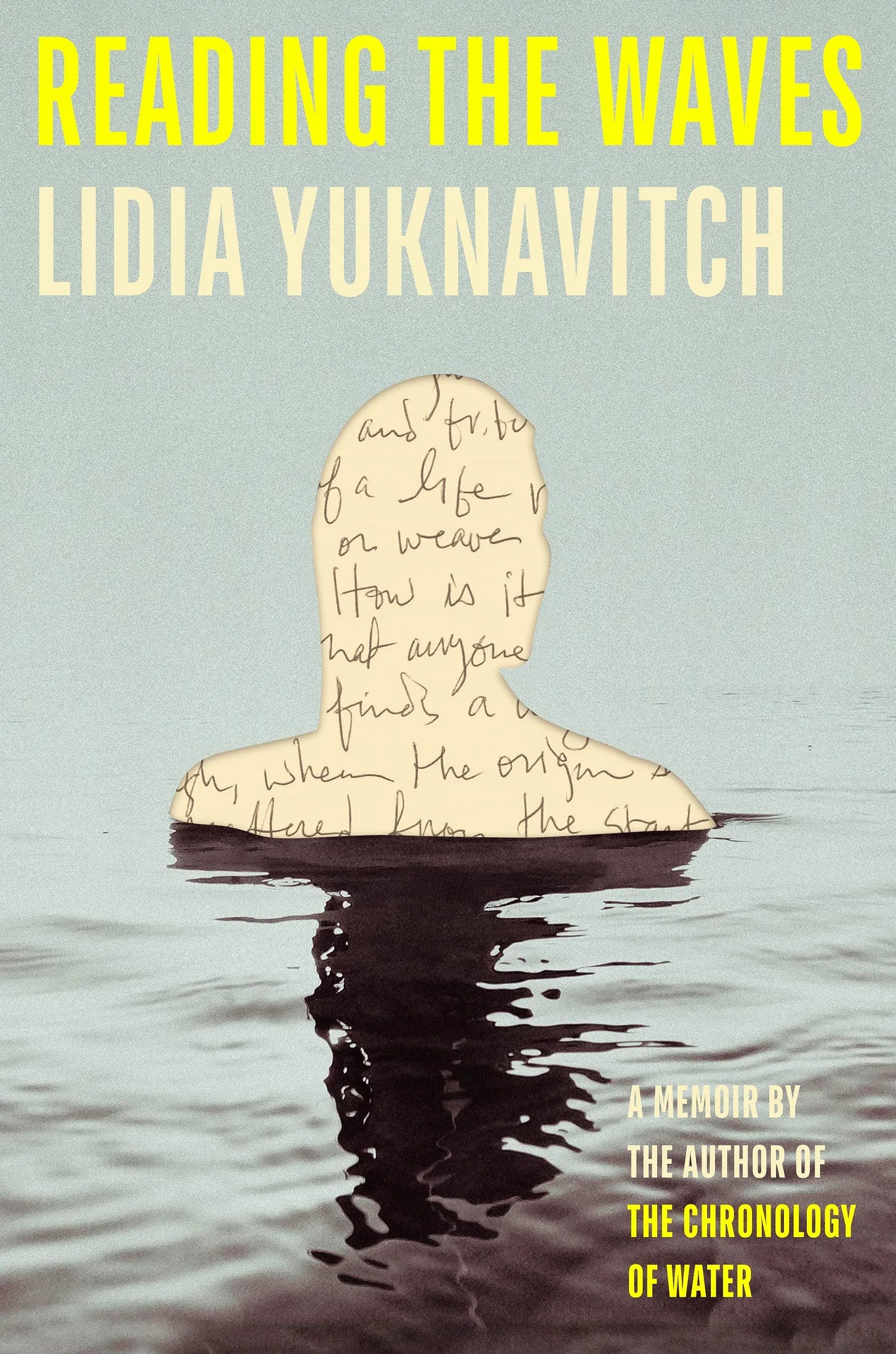

Especially not easy for Lidia’s latest book Reading The Waves. With clarity, electric insight, and gentle curiosity, Lidia examines the stories she’s told herself about her life and the ways these stories have impacted her relationship with herself, with others, and with her body. Using the gifts of storytelling, she explores what happens to these stories if she moves to a different viewing location. Does the hold they have on her body and her spirit loosen?

Lidia is the award-winning author of the memoir The Chronology of Water, which Kristen Stewart has adapted into film, Thrust, The Book of Joan, The Small Backs of Children, Dora: A Headcase, and The Misfit's Manifesto, based on her TED Talk, On The Beauty of Being a Misfit, which garnered 4.5 million views. She is the founder of the glorious literary arts organization Corporeal Writing.

If you’re interested in reading more, I’ve lifted the paywall on my first interview with Lidia for Beyond. And I’ve included the link to our interview for Longreads.

Enjoy!

xJane

I’m sure you won’t be surprised that I want to start with a question about trees and animals and dirt and water – all of whom you thank in your acknowledgements! And in your final chapter you write, “Your family of origin is only one kind of origin. Your ancestors track back to trees, water, minerals, space, otherness.” Can you talk about your relationship with these elements and with nature in general?

I don’t think of it as, “Oh, I have a neato relationship to nature.” I think of it more like, “I’m getting closer to understanding how non-human existence is something we are intimately related to.” As a kid, coming from an abusive household, I spent a lot of time in our backyard and in this vacant lot across the street that had big evergreens in it. I was drawn to talking to actual trees and dirt and water, it comforted me and it helped me in a chaotic childhood situation.

What I wrote about in Reading the Waves as an adult is different than that. That was a kind of kid intuitive magic to go to non-humans for help. At this point in my life, I’m beginning to let myself learn that my human existence is this tiny, tiny piece.

It's interesting you said when you were a kid that you were talking to the trees because you write in this book and elsewhere, that as an adult you’re still talking to the water and the trees and the rocks and the seals. What does talking to these beings look and feel like to you? Are you speaking your words out loud? Are you hearing their responses? Or is it some kind of vibrational experience in your body?