Lauren Aliza Green On Marriage, Adultery, and Grief

What Our Literary Plots Reveal About Us!

I first learned of Lauren Aliza Green through my good friend and fellow Substacker

. Caroline has pretty much impeccable taste and I figured anyone Caroline thought was a lovely person who wrote beautifully probably was. I figured right.Lauren’s beautiful new novel, The World After Alice, was published earlier this month and it carries shining blurbs from both Ann Napolitano and Elizabeth McCracken! The story takes place in the wake of tragedy: the death of sixteen-year-old Alice Weil. Now, twelve years later, Alice's brother Benji and former best friend Morgan surprise their families with a wedding invitation to Maine. As the estranged families come together for the first time since Alice's funeral, old flames are rekindled and buried secrets abound.

Lauren has also written A Great Dark House, winner of the Poetry Society of America's Chapbook Fellowship. Her work has appeared in Lit Hub, American Short Fiction, Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. She was named as one of Forbes’s 2024 30 Under 30 in Media. She lives in New York City with her husband and bunny rabbit.

I hung on every word of this essay contemplating not only how I crafted my stories, but also my life! I think you’ll have the same reaction! As always, I’m keen to read your thoughts in the comments!

⭐️ Lauren is generously gifting three readers an autographed copy of The World After Alice! If you’d like to be one of the recipients, please add “Alice” after your comment. The winners will be chosen at random on Monday, July 22nd and notified by email. I’m excited for all of you! (Shipping is limited to the United States) ⭐️

On Plots: Marriage, Adultery, Grief

While promoting my debut novel, The World After Alice, I’ve frequently encountered the dreaded question: “What is your book about?” The simple tagline—a dysfunctional family reunites in Maine for the first time in twelve years to celebrate an unexpected wedding—omits that this is largely a book about grief.

Part of my descriptive challenge lies in the fact that the book weaves together three distinct storylines: marriage, adultery, and grief. Such plots have been around forever and, I suspect, will continue to endure. Every few years, however, the question of whether the marriage plot is dated, defunct, or otherwise dead hits the literary discourse. Take this recent book review from the New York Times, where the writer asks, “Why bother with the centuries-old marriage plot in a no-stakes, no-strings-attached world of total freedom to change one’s mind without consequence?”

While it’s true that matrimony no longer serves the same social function it once did, it is equally true that the marriage plot itself has never been about marriage but rather about something far greater: the protagonists’ internal struggles. I am not the first to say this. Adelle Waldman, writing for The New Yorker in 2013, argues, “If we look closely, we find that much of the [marriage plot’s] strength derives from the internal and the timeless—from conflicts rooted in the perversity of human nature and the persistent difficulties of social life.”

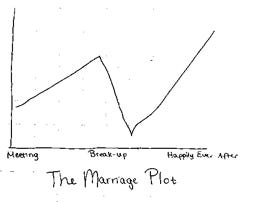

The marriage plot is, above all, a teleological one. There is no mystery at its heart. Readers expect the characters to join together by the novel’s end. The enjoyment of these books, their gratification, derives from seeing the protagonists grow and change as individuals before they say “I do.”

Consider Jane Eyre. By the time Jane and Rochester wed in chapter 38 (famously, “Reader, I married him”), Jane has gained financial independence, a family of her own, and a sense of autonomy. Rochester, for his part, has lost his eyesight and thus been humbled. Had he and Jane married during their first engagement, before the reveal of Bertha Mason, Jane’s strength might have remained unrecognized. However, with the developments in the last third of the novel, Jane comes to retain her individualist spirit so that she is not subordinate to her husband but established as his equal. The fulfillment of their union, and the reader’s satisfaction, depends on her growth outside of matrimony.

While the traditional courtship plot culminates in an exchange of rings, the narratives of grief and infidelity track less linear routes. In the grief plot, the protagonist spins around in circles, orbiting the absent object of his or her love. Nowhere is this better depicted than in Yiyun Li’s Where Reasons End, which imagines a conversation between a mourning mother and her deceased son. Quoting Alice in Wonderland, the son says, “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.” Oh, yes—what better definition of grief than this?

The grief narrative folds back on itself, mimicking the cyclical way the sufferer cedes their every thought and feeling to what is now gone. In my novel, I found that this cyclicality provided a nice foil to the goal-oriented plot of courtship mentioned earlier, which unfolds not in the aftermath of an event but in the before-times, when it is still possible for the protagonists to contemplate whether the hoped-for will come to pass.

If we were to graph it, the marriage plot might look something like this:

While the grief plot, that most elliptical of narratives, might look like this:

In between these two falls the adultery plot. The adultery plot—that of Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary—typically sees its protagonists meet a tragic end, as illustrated below:

All three plot structures—each of which weighed heavily on my mind as I pieced together The World After Alice—rely on the “I” being forced to redefine its identity in relation to another. In the marriage plot, the “I” must learn how and who to be with the “you”; in the adultery plot, the “I” severs themselves from the “you”; and finally, in the grief plot, the “I” must continue to live without the “you.”

These plots force us to redefine what we know of ourselves. What does it mean to join with someone in marriage, or to separate from them through adultery, divorce, or death? How do we reconcile our Western notion of the “I,” which values autonomy above all else, with a desire to transcend that “I” and connect with another? In an 1864 diary entry, Dostoevsky wrote, “To love a person as oneself according to Christ’s commandment is impossible. The law of the self is binding on earth. The I stands in the way.”

Dostoevsky further explores this notion in Notes from the Underground, where he introduces readers to the underground man: a self-conscious figure whose obsession with the laws of mechanical science paralyzes him. If human beings are subject to the laws of science, the underground man wonders, then what agency does any of us have? To underscore this point, he refers to man as a “piano-key” or “the stop of an organ”—pressed against, acted upon.

His view only changes when he meets Liza, a prostitute who glimpses beyond his cynical exterior to the soul underneath. When he flies off into a spiteful rage against Liza, she doesn’t run away as he expects but instead rushes toward him and throws her arms around him. It is a startling moment in the story. For a brief instant, readers see the “I” do the impossible, at least by mechanistic laws: it joins with another to become a “we.”

I contemplated this moment a lot while working on The World After Alice. There are certain times in life—heightened moments of grief or love—when the emotion is so powerful and overwhelming, language itself breaks down. And yet compassion is still possible in these moments, available through other means. Here’s a snippet from my book illustrating this in real time between the groom and his mother:

“With a movement unexpected to them both, Benji reached out and pulled his mother into an embrace, amazed at how defenseless she felt in his arms. It occurred to him how few times he’d initiated such a gesture. How many wasted opportunities, when such a touch might have conquered the space that twelve years had set in their way.”

In moments such as these, the veil of reality is momentarily lifted. Something tender and true breaks through. The self is made both clearer and more obscure, stripped of the identities they’ve long clung to. “It was the year of my disintegration,” the unnamed narrator of Where Reasons End says, “and I could find few delusions to live for.”

In the absence of delusions, what remains? This was the question I set out to answer in The World After Alice. It is a question of existence, one that shatters the binaries between self and other, life and death. While I may shudder at describing my book as a simple “wedding novel,” I remind myself that the stories of our relationships form the essence of our lives. Nothing could be more important than that.

If you enjoyed this essay by Lauren, you might also like this one by Mary Pembleton:

⭐️ Beyond is a reader-supported publication with the goal of bringing as much light as possible into this world of ours. If you value my work and would like to support it, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

Wow. I have never seen someone distill those plot lines down in such a beautiful way. I see now how it applies to not only writing but also across my life. Thank you as always Jane, for giving us all much to think about through sharing such a brilliant essay from Lauren.

Alice 💚

Beautiful!! In other words, life, relationships and identity are complex. I couldn’t agree more! Your novel sounds intriguing. I would love to write “Alice”, but I am in Canada :( I very much enjoyed reading this essay and am inspired by it! Thank you.