Finding Community: A Conversation with Omar El Akkad

On the obligation of witness, erasure of history, the damage of insatiable systems, language as a conduit for meaning, the choice of hope, and the joy of community.

Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

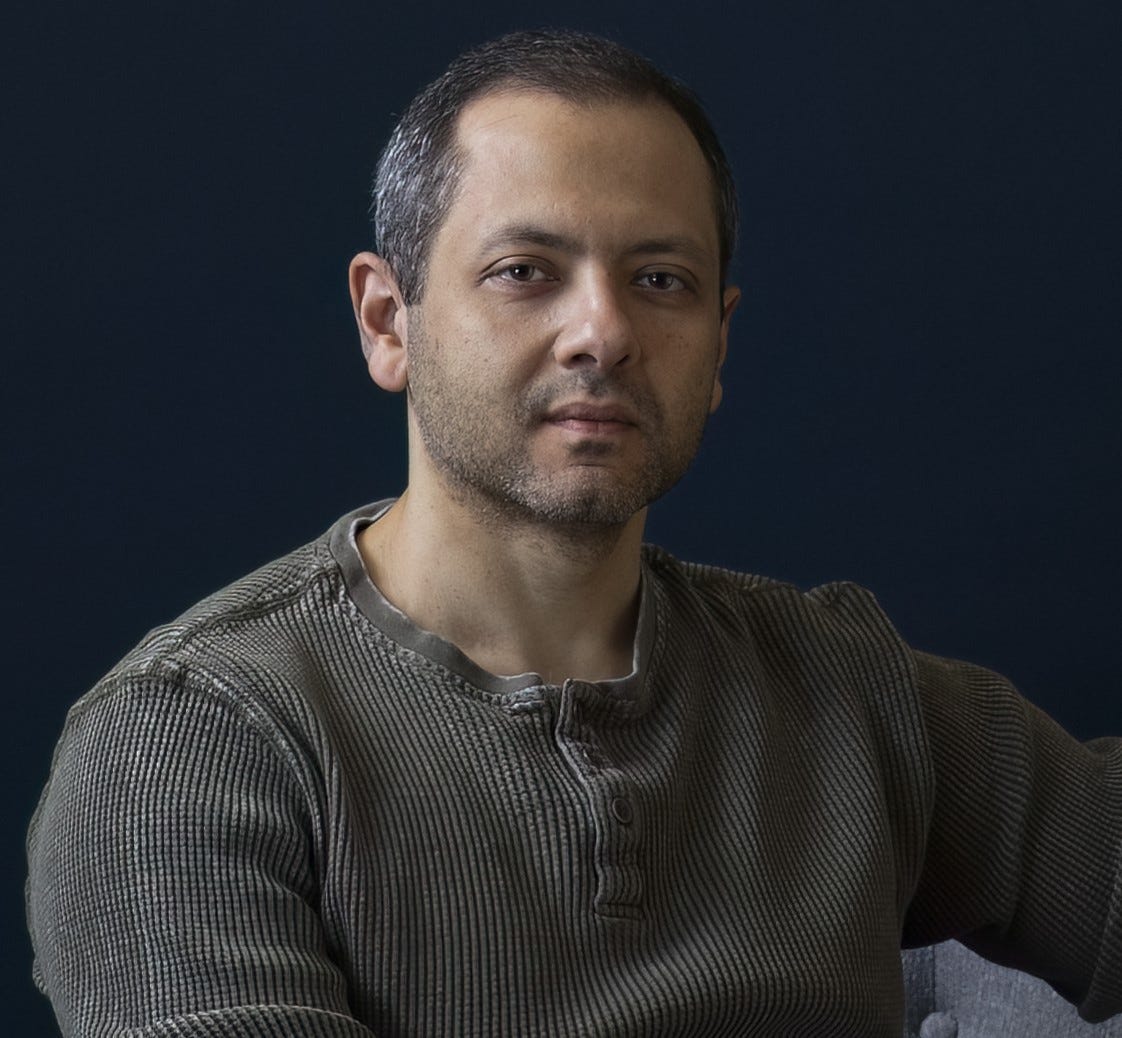

Omar El Akkad’s writing is staggeringly, exquisitely beautiful. Like, makes-my-heart-swoon level. It is also staggeringly painful. He writes about war and cruelty and dishonesty and family and humans trying to help one another and sometimes succeeding and sometimes failing and hope and losing hope and friendship and betrayal and trauma and tragedy and broken systems and colonialism and empathy and humanity and love.

His words have changed me.

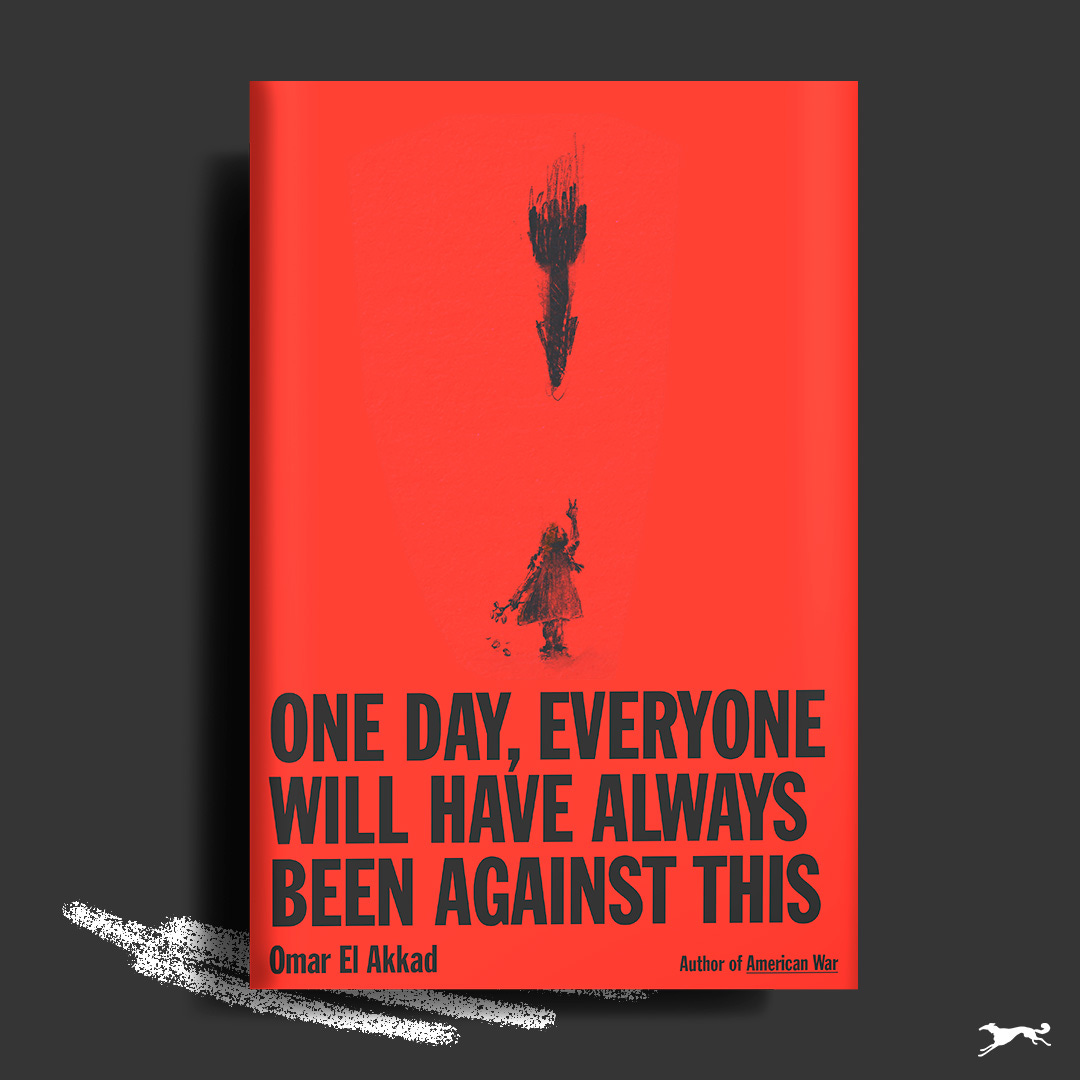

His most recent book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, is a Nonfiction Finalist for the National Book Award. In it, Omar, an award-winning journalist, examines the genocide in Gaza and the role of the West through the lens of his own life. Born in Egypt, Omar grew up in Qatar, moved to Canada as a teenager, and later settled in Portland with his family. Once hopeful about the freedoms of the West (no books with blacked out words!), he soon came to recognize that these shiny promises for some, were built upon the broken dreams and bodies of others. One Day is a grappling with how to be a father, a husband, a friend, a writer, a citizen in a country that is causing harm to so many.

Omar’s first novel American War follows Sarat Chestnut from a curious, trusting, earnest little girl to a ruthless warrior shaped by lies, cruelty, and betrayal. His second novel, What Strange Paradise, follows another child, this time a refugee washed up on the shores of a small island, as he, too, seeks safety in an increasingly hostile world.

Despite the heaviness of the subject matter, the writing is tender and elegant. Omar manages to inspire hope, compassion, empathy, even joy, in face of seemingly insurmountable brutality.

I so enjoyed speaking with Omar. I think you will be as deeply moved by his words as was I.

xJane

⭐️ Omar is generously gifting three readers an autographed copy of One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This! If you’d like to be one of the recipients, please add “DAY” after your comment. The winners will be chosen at random on Monday, November 17th and notified by Substack Direct Chat. I’m excited for all of you! (Shipping is limited to the contiguous 48) ⭐️

Before an interview, I reread everything the author wrote to make sure it’s fresh in my mind. So I reread your three books back to back. Omar, on one hand, it’s the most astoundingly beautiful work. On the other hand, it almost broke me. There’s so much hope and light in your books. And there’s so much suffering. How do you carry all the rage, the sorrow, the heartache, the injustice? Are there practices you engage in not to lose your mind or your heart or break your health?

That’s a good question. I remind myself that for the entirety of my professional writing career, and this goes back to my decade as a journalist, as well as all my work as a novelist and now writer of nonfiction, I have essentially been a tourist in someone else’s misery. Whatever my powers of empathy, whatever my ability to sit with someone else’s pain, I still have the fundamental privilege of being able to get up and walk away.

Even with that privilege, it’s still a lot. Do you go running? Do you meditate? Are there practical things you do to keep yourself in balance?

I’m quite often happiest when I’m alone when something of consequence is happening. The only thing I really do for fun, per se, outside of reading, is rock climbing. The kind of rock climbing I do is the solitary version. It’s bouldering, where it’s just you on the wall. I find that I’m able to reset, or at the very least, channel my rage in a way that is much more concrete. You fall off the wall, you yell, maybe you punch the wall, and you go back to it. That’s much more manageable than the abstractions we’re talking about.

Do you feel some an obligation to witness and write about the sufferings in this world?

I do, but I don’t necessarily think that’s a good thing. Because whenever I try to break down the reasons why I do, they’re not especially honorable.

First is the basic obligation of witness. Through forces that I had nothing to do with, I was born into a life where I am largely insulated from the worst of what is done in this world. On top of that, much of the worst that is done is paid for with my tax dollars. I wrote a book about the genocide in Gaza. I am paying for that genocide. Given that combination, the very least I can do if I still want to call myself a writer is bear witness.

Then there’s a more selfish reason, which is there’s a difficulty that comes from not doing it. Which is to say, towards the end of my life, when I am thinking back on how I behaved in this world, what I did, what I didn’t do, I want to be able to say at the very least that I did bear some kind of witness, that I did say something. I think that the internal reckoning with having said nothing will, in the long run, be a more intense pain than anything that comes with the alternative.

Do you ever feel, I don’t quite know the right word, guilty is coming to mind, that you’re not more in the thick of it? Listening to you, I’m thinking of my father who grew up in London during World War II. As a child, he was evacuated. That has haunted him his entire life. He feels like he should have been in London. He should have been bombed. Does this make sense to you?

Certainly there are times where something approximating what you’re talking about is very hard to set aside. That’s in part because I know that a lot of the people in the world subjected to the kind of horrors that much of my writing is concerned with look like me. They have names similar to mine. They have ethnicity like mine. They follow religions that I do. And my position of being relatively insulated from that is not due to some function of merit, rather just luck.

If I had been born in some other context, I would not be sitting here talking to you. I might be in a secret prison in Egypt, or looking for work, or I might not have made it to this age to begin with. It’s very hard to think of these things and not feel some sense of wholly fraudulent and self-centered shame.

Shame. Maybe that’s a better word?

Even that is worth dissecting because it implies that resistance to institutional evil is an obligation that can be individually delineated. But that’s not true. In a world that is anything but fully sociopathic, none of us should be walking around with a blueprint in our back pocket for how to, for example, best oppose a genocide. And so, a lot of us are just muddling through these moments that are much, much bigger than we are.

Whenever that feeling comes up, I try to remember that, first of all, it doesn’t really matter how I feel. And second, the only solution to whatever it is I feel is to find solidarity with others and to find a sense of community, because there’s no way I’m solving any of this stuff on my own.

Listening to you now, and in other interviews, and having read your books, you strike me as quite humble. You set yourself aside. Do you feel like you’re channeling something or that something’s moving through you when you write? You often say, “I don’t matter. What matters is that I’m doing my best to articulate what’s happening.”

When I’m working on any piece of writing, the place I’m trying to go is the place where something is happening and I don’t have control over it. There’s this thing John Cage said about how the artist, when they walk into their studio, walks in alongside everybody they’ve ever met: their critics, their fans, previous versions of themselves, you name it. But as you sit down and start to do the work, one by one, these people get up and leave. And if you’re very, very lucky, even you get up and leave.

I love that! Your latest book is, in part, about Gaza. What are your thoughts on what’s happening there at the moment? Both sides say they want the ceasefire. It seems precarious, at best.

My sense of the ceasefire is no different than my reaction to every previous quote unquote ceasefire in that it’s always the expectation of one side can violate the rules of the ceasefire with impunity. Anything that causes the scale and scope of suffering in Gaza to decrease is something to celebrate. But none of this changes the fundamental terms of the asymmetry. None of this changes the fundamentally colonialist nature of what’s happening. I think what we have been watching play out in Gaza for the last two years, and in Palestine for the last seventy-seven years, is no different than the trajectory of any other colonial endeavor.

Colonialism, like whatever stage of capitalism we currently live in, is insatiable by definition. It has no ceiling. It has no moment at which the system says, “Enough, I am satisfied.” So the non-existence of whoever gets in the way of that machine is always implied. We might be more horrified when the pace at which that non-existence is enforced seems faster than normal. But even the baseline normal, and that the baseline normal exists, is horrific in and of itself.

What I come back to is this notion that we as a species, if we don’t make a fundamental change to the way we live, are going to more ourselves to death. That this obsession with more and more and more is going to undo every last thread of convenience that we have convinced ourselves is betterment.

I try to get at this as often as I can because I live in a part of the world where every year my Amazon packages arrive faster and my internet gets a little faster. It’s very alluring to conflate that with life getting better. But it’s not getting better. Life is getting colder and more convenient. And the fuel that is making this machine move is a whole bunch of dead brown people on the other side of the planet.

What do you see as the connection between dead people in Gaza and getting your Amazon package faster?

Over the last two years, I’ve done a pretty good job of wrecking my relationship with literary organizations that I previously had very good relations with. A central reason why that is the case is because I’ve been agitating for those organizations to cut ties with sponsors who invest in weapons makers.

Over and over again, when I do this, the counter-argument comes in two forms. The first is that we’re doing nothing wrong. All money is covered in blood, and we simply take it from these corporations and hand it over to writers, and that’s a good thing, right? The other being, how is picking on our little organization going to put an end to genocide?

On a surface level, they’re both fairly compelling arguments. But if you follow the implication, you end up in a place of pure nihilism, because effectively the argument is that it can never get better than this, and all money is tainted so why bother trying to do anything?

One of the main ways in which I try to oppose what is happening in Gaza is trying not to do business with entities that I feel are directly profiting off this. If I were to follow that in any principled sense, I would shut down the computer that I’m talking to you on now. I’ve cancelled my Spotify account. I would have to stop using YouTube and Gmail. I’d have to stop using Microsoft. I would eventually have to take leave of the world as I know it in my privileged part of the world.

I’ve heard you say that you have hope about Palestine. Can you talk about hope? Are you a naturally hopeful person, or do you have to go through some step-by-step process to get yourself to that place?

I have no choice but to be. I always go back to this virtual event I was doing for a climate anthology. The final question that was asked was something like, “what does hope look like for you?” Everybody gave the sort of answers you’d expect, except the last guy, whose house had just burned down in the California wildfires. He said, “There is no hope. We’ve screwed things up too much. But we must behave as though there is.”

I think about that a lot, because left to my own devices, I’m very susceptible to a kind of cynicism that borders on nihilism. On top of that, I come from a long line of malfunctioning hearts. The men in my family don’t live very long. I have children now. When we talk about things like climate change, for example, I don’t have the privilege of simply assuming that the systems that I’ve come to take as normal will continue to exist, even if they teeter on the edge for the rest of my lifetime, and then some future generation can deal with it. That future generation is my children.

I come back to this notion of what insatiable systems ultimately do, which is that they become cannibalistic. They grind themselves up. Where I live in the United States, there has been this ongoing attempt to make life infinitely better for an infinitely smaller number of people. If you live in this country and you have billions of dollars, you have access to the best healthcare in the world, the best everything in the world, while at the same time, an increasingly larger number of people are forced to the other end of the spectrum, where they get nothing. That is unsustainable in any context.

This, in a perverse kind of way, is where my hope finds a lot of its fuel. This is no different in Palestine or in Sudan, where the UAE-backed militia is engaging in some of the most horrific things I’ve ever seen in my life. This is no different in any fundamentally colonialist or insatiable endeavor. I have to believe that this growing number of human beings who are cast into the abyss eventually form a powerful enough force to overturn that system because the alternative is all of us being cast into that abyss until there’re two colonialists or two capitalists left, and one of them pushes the other of the edge of the cliff.

That wonderful sentence in American War just popped into my head about how the first thing they do is they erase your history. Do you feel like that’s happening right now in America, in Palestine, in the world?

It’s a vital component. I don’t think any of this machinery of empire can withstand an accurate accounting of history. It’s simply incompatible. History has to be a deeply malleable thing in the eyes of any empire both as a means of aggrandizing the empire’s own history and whitewashing its crimes, and also as a means of implying that whoever gets in the way of empire has no history, has no claim to civilization.

I grew up in Qatar. The background of that place eventually leads you to a Bedouin culture, which is a culture that has to survive under very very harsh conditions so our obligation to take care of one another is a central.

Last time I was in Qatar, which was exactly a year ago, we went camping in the desert. I was teaching at Georgetown there, and the American professor was driving, and we got stuck in the sand. We’re out in the middle of nowhere and the sun’s going down and panic is setting in. We see this Land Cruiser driving by and hail them down. A bunch of Qatari guys come over. As soon as I saw them, I knew we were going to be okay. They will never, ever leave us here. It’s unacceptable to them.

Sure enough, they called their friend to tow us out. He didn’t have the right chain. They sent the guy two hours back to get the right chain. While we’re waiting, they open the back of their truck, they pull out cushions, and they make a little majlis for us and they started serving tea. None of this was remotely surprising to me, because I know that this is a fundamental tenet of this culture. At the end, when they pulled us out, I was thanking the guy, and he shook his head, and he said, “it’s our duty.”

So beautiful.

When I go back home to the U.S, and watch a movie, and it has someone who looks like that in it, he’s going to have a bomb strapped to his chest. Overwhelmingly, that is who I am expected to believe these people are. That is an erasure of history, but nobody would call it that. They need to destroy that history—it’s not tangential, it’s not a side effect, it’s a fundamental load-bearing beam of empire, and it might be the most insidious one.

You write about how language is also important in harming others, even if it’s just laying the foundation for further harm. You start with how white Westerners living in another country often for economic reasons are “expats.” While non-white Westerners are labeled “aliens” or “illegals.” And build toward more complex examples. Is language also a piece of erasing histories?

Yes, it’s a fundamental part of the endeavor as well. It’s been going on for a very, very long time. For example, one of the terms used in the United States to describe the Civil War was “the late unpleasantness.” “Collateral damage” dates back to Vietnam. Any distance you can put between the conscience of a privileged population and the atrocities committed on its behalf is a natural lubricant that allows those atrocities to take place.

One of the reasons that I focus so intently on language is not only because it’s one of the more insidious means of doing this but also because this is what I do for a living, I work with language. Which is to say that I work with the intention of trying to make meaning. So when I see language used for the unmaking of meaning, it hits a nerve in a way that many of these other factors and currents don’t.

If we’re going to call ourselves writers, we have more than just an obligation to write, we have some obligation to stand in defense of language as a conduit for meaning rather than language as an antagonist to meaning.

You write a lot about severance in all three of your books. Can you talk about this? In particular, the ways that we have severed ourselves from nature.

There is a severance, particularly from something like nature, that is required under the dominant systems we live under. Severance from nature and severance from one another, which are intertwined. One of the reasons they’re intertwined is because they give us many of the same things: A sense of belonging. A sense of having a relationship with our lives that is more than transactional. A sense of what it means to be and to love. All of that is deeply, deeply vital to the human condition and, simultaneously, deeply inconvenient to these systems of endless taking. The more I find solace in the world around me, the more I find solace in the people around me, the less I’m sitting around scrolling through Amazon, looking for trinkets to fill that void—and that makes them deeply inconvenient to the system.

I don’t think it’s accidental that we live in a world where what in any healthy society would be considered our most prioritized connections are increasingly being made our least prioritized connections.

But I also think of a different kind of severance, which is the walking away from that system. Systems of power have a much easier time punishing us for active engagement than they do for negative engagement. They have a much harder time punishing us for what we don’t do, what we don’t buy, what we don’t engage with. That’s why so much of my writing is obsessed with this notion of dissecting the act of walking away.

You write in One Day, “What to do with someone who says, I will have to no part in this, when the entire functionality of the system is dependent upon active participation.” And later you talk about dismantling it now and building another thing entirely. How? What does that look like?

The most frustrating thing is that the vast majority of the process is deeply, deeply imperfect and seemingly ineffectual because we tend to view this from an individual prism. I’m personally no longer going to Chevron gas stations. I have cut ties with the company who used to host my website because they’re on the boycott list. But I am not even a rounding error to any of those companies. So this sense of impotence is seemingly perpetual. But there’s something that’s happening, which is to say that whether I like it or not, I am joining a bigger community. I’m joining a movement, and in fact, that may be the most impactful thing I do—letting myself know that I’m not just one person throwing pebbles at a billion-dollar corporation.

So whenever I’m dejected about this act of moving away from one system as the first step towards building something else, and how monumentally huge a task that is, I have to keep reminding myself, I’m not working alone, that I’m part of a bigger initiative. No matter how difficult that will be, and how likely it is to fail, it’s my only way out. Because the alternative is adhering to the system in place and developing my muscles of obliviousness to make it so that I can continue to live this way while simultaneously destroying my conscience.

So much is hard right now. Where are you finding the joy?

A lot of joy has left life over the past two years. I’ve seen things that I can’t unsee. But I still derive immense joy from being with my children. I derive immense joy from watching entire generations, these are people half my age, who are finding community for the first time in their lives. Whenever I would talk to the folks who were part of these encampments at the universities, one of the things that would come up over and over again is this sense of finding solidarity, finding something that was more than a personal trajectory of ambition. I derive great joy from that.

But mostly it’s from being around people I love and recognizing what an astounding piece of good fortune it is to be able to spend time on this earth doing that. I remember reading this thing someone once wrote about their creative writing professor telling them that if they really, really thought deeply enough about the act of going to the supermarket and buying groceries, they would turn into a puddle. They would be overwhelmed by the grandeur of that.

As vicious as we so often are to one another, it’s an incredibly astounding thing to be in the world and to have this experience. I try to remind myself of that every now and then.

If you enjoyed this interview with Omar, you might also like this one with Lidia Yuknavitch:

Deep gratitude to my paid subscribers whose support keeps Beyond going, and allows me to pay contributors. Without you, none of this could happen. ❤️

If you read this newsletter regularly, if you discover new writers here or new ways of seeing the world, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Not only do you help sustain my work, you help keep heaps of (often quite ill!) doggies and kitties off the streets.

⭐️ If you’d like to support my work without a subscription, here’s my link to Venmo and Paypal. ⭐️

Thank you for reading! I love hearing your thoughts!

"And second, the only solution to whatever it is I feel is to find solidarity with others and to find a sense of community, because there’s no way I’m solving any of this stuff on my own." ❤️

What a moving interview. One to be read again and again. Like that song we play on repeat. The story shared of getting stuck in the sand and the help given and tea served and the understanding "It is our duty" has me wondering deeply about my own duty. Thank you, truly. Day