Father Knows Best

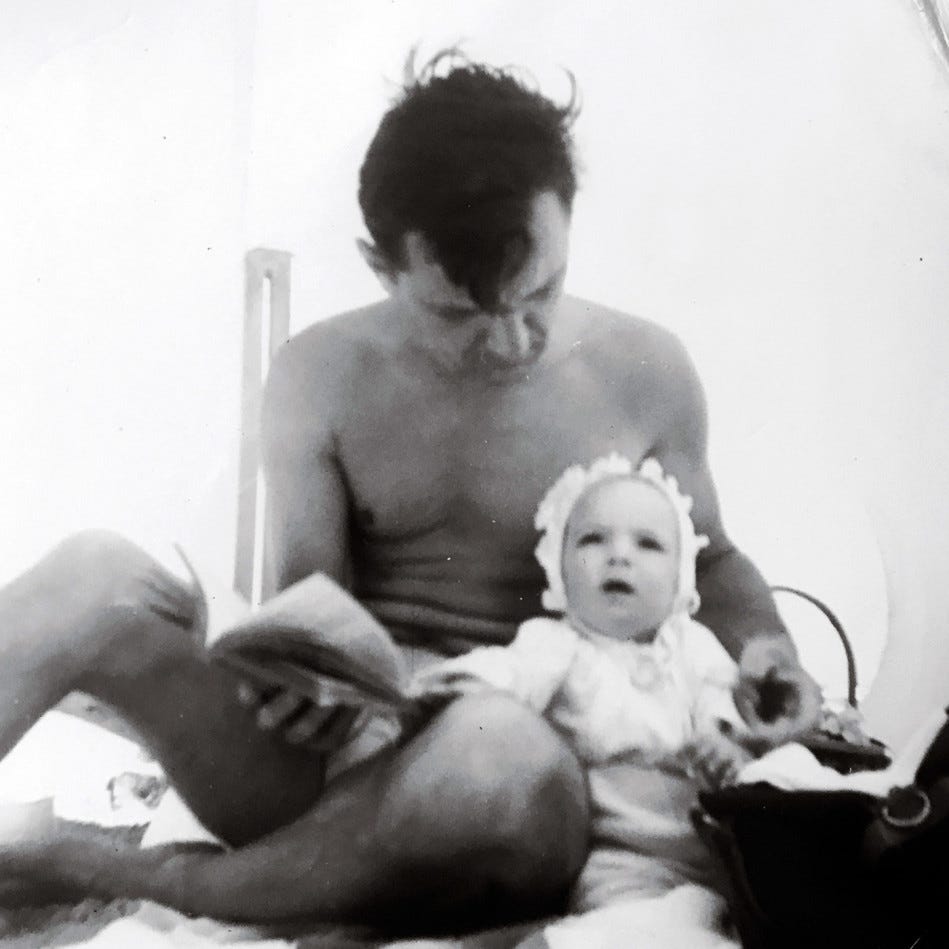

My essay on how in the terrifying aftermath of head and brain injury, my dad believed me when the doctors didn't.

Hello Darling Beyonders,

The return of this head pain has been tough. In addition to being, well, painful, I’ve discovered it’s a trauma trigger. Whilst, thank goodness, the pain is nowhere near the staggering levels I’ve lived through before, the fact that I’m experiencing head pain at all is flooding my nervous system and brain with lots and lots of memories. Memories of how terrifying my post-head-and-brain-injury life has been on more than one occasion.

But there are also, unexpectedly, beautiful memories. Just the other day, I was out walking Delilah and suddenly craved a cheddar cheese and avocado sandwich cut into fours. That was what my dad made me every single day for lunch during the three months he lived with me when I first moved back to Michigan and my health collapsed. He gave himself so completely to my care even though years later he shared that he, too, had been terrified. I have always loved the word daughter, in fact it’s one of my favorite words, alongside beloved. And during those three months, I was indeed my dad’s beloved daughter (and, of course, still am!) And just as the head pain can return me to the hardship and fear, the mere thought of the sandwich returned me to my dad’s deep love.

A few years ago, I wrote an essay about the way my dad stood by me that appeared in O, The Oprah Magazine. It was the first and only time they published an essay in Connections that ran for two pages, double the normal word count. Quite an honor! After suddenly craving that love sandwich on Monday morning, I decided to share the essay with you today. I hope you enjoy it!

Welcome to all the new faces. There are so many! I’m terrifically happy to have you here! I encourage you to check out the archives. There’s so much goodness there!❤️

And congratulations to our three lucky Badass Medal winners: Caryn Linda, Amy Rea, and Mary Hutton Fruchter. What a lovely way to celebrate Beyond’s Second Birthday!

Please do let me know what you think of the essay in the comments, Beyonders. I always love hear your thoughts! I should add when this essay ran in O, a few people wrote to me to let me know that ECT has had a successful resurgence and is helping many people. I’m glad to hear this! But that was not my mom’s experience and my essay reflects what she shared with me over the years.

Dot Dot Dot Dash

Shortly after I was born, my mother was hospitalized and received daily doses of shock treatment. She had what would now be diagnosed as postpartum depression, but in the early '60s, much of female psychological distress was still called hysteria.

My father is a kind and intelligent man, so the doctors must have presented a convincing case to get him to agree to have my mother's brain lightning-bolted with electricity. Because agree he did. And from this improper care, a family legend was born: My mother was crazy. I not only bought into this myth, but also harbored a fear that I was destined to become crazy, too. So part of me wasn't surprised when, in January 2008, the prophecy began to bear fruit.

It was after midnight when I called my father. My heart had been racing for several days. I was tired, yet my nervous system was locked in go, go, go. My skin had turned yellow, the whites of my eyes appeared gray, and my normally pink nail beds were colorless. Though not usually one to shed tears, I couldn't stop crying. The room was flipping over. My short-term memory had all but disappeared; when I took my daily walk, I was unable to find my way home, even from a block away.

Also the pain was back. Since the late '90s, when a tabletop in a furniture showroom fell on my head, I'd experienced bouts of debilitating nonstop head pain, sometimes lasting up to a year. Now it felt like my head was locked in the familiar ever-tightening vice.

My 80-year-old father was not unaccustomed to my calling and asking him to bail me out. In high school, I'd sneaked out many times to clubs and parties from which he often had to collect me. At 20, when I dropped out of college and moved to New York City without a job or a contact, he was my emotional support system. So though it had been a while, he knew to take a midnight phone call from me in stride. But on this night, something in my voice concerned him enough that he lurched out of bed, leaving my 79-year-old mother, who'd been healthy and self-sufficient for decades, and drove an hour to my house in his pajamas. He ended up staying three months.

"It's connected to the head injury," I'd say, as red-hot adrenaline shot up my arms. "Yes. And we're going to fix it," he would say in his charcoal London baritone.

I wasn't sure either of us was right. I'd never told anyone about my mother's hospitalization, in part out of respect for her privacy and in part because I feared they would start to see me as I saw myself—teetering on the brink. I'd gone to therapy diligently for years, working to stay sane. Now I worried it had all been for naught.

Every day, every hour, I would ask my father, "Am I going crazy?" By which I meant: Am I fulfilling my role in our lineage? Each time, he would reply, "Absolutely not." By which he meant: I won't let that happen again.

After he arrived, every week involved a visit to some sort of doctor. I told each one about the head injury. I explained that I'd lived through crushing endless head pain before, and though I'd never experienced accompanying symptoms this severe or wide-ranging, I knew the old injury was to blame. Doctor after doctor dismissed my self-diagnosis with a hastily scrawled prescription for a psychotropic drug. A few suggested I try not to think so much.

But my father stood by me. Every morning he made me oatmeal; lunch was always a cheddar and avocado sandwich lovingly cut into fours. On Sundays, he'd drive to his house to pick up enough of my mother's home-cooked dinners to get us through the week. When the adrenaline rushes were particularly bad, he ran with me around the kitchen table and up and down the stairs until the surges dissipated. At night he sat in the rocking chair beside my bed and read to me from Winnie-the-Pooh. More complicated plot lines confused me.

On gray, slushy afternoons, my father would tell literal war stories—how, as a child, he'd been evacuated from London and separated from his family. And for the first time, he told me that when he and my mother arrived in America in 1954, the job he'd been promised didn't exist. So he'd trudged up and down the streets of Detroit in a woolen English suit during a muggy August, making inquiries at auto-engineering firms. "I was disconsolate," he told me. We all suffer, he seemed to be saying. You haven't been singled out.

He also encouraged me to think positively and have patience. Thanks to his profession, he had a cache of car analogies about bringing the "vehicle" into balance. He repeated them so often that I could soon speak with some authority about carburetors, pistons, and cracked aprons.

Above my kitchen sink, he posted three dots and a dash: Morse code for the letter V, echoing Winston Churchill's World War II–era V-for-victory sign. His daughter, too, would rise again.

On my worst nights, I rushed to my father in tears, wondering whether I should, at last, go to the emergency room. He'd gaze thoughtfully at me and say no. Then he would tell me a story. The evenness of his voice, coupled with his very presence, helped me feel as good as I was able to. But the next day, the cycle would begin again: "It's the head injury," I'd say. "Yes." "Am I going crazy?" "No." I didn't want to let him down.

At times I would imagine my mother in a hospital robe, being led by a stern-faced nurse down a narrow green hall to a room where she would be instructed to lie on a bed, her heart racing. There, they'd strap down her wrists and ankles, preparing her head for the electrodes. Then the image would change; it was me being led down that hall.

One day my father took me to see yet another physician. We drove an hour to Dr. Denton's office in my dad's Crown Victoria. Along the side of the road, daffodils were in bloom. The doctor, a small, straight-backed man of few words, actually believed me. In his office, my father and I finally saw an X-ray of my head and neck. It turned out my original injury hadn't healed properly, and my head was on crooked, reducing the oxygen supply to my brain.

"Worst case I've seen in 28 years," Dr. Denton said, indicating the precarious angle at which my skull was perched on my spine. (How had I not noticed this in a mirror? How had friends and family missed it? Why hadn't the previous doctors known that symptoms of anxiety are uncannily similar to those of insufficient oxygen to the brain?) "You must have a strong will," Dr. Denton told me. "Otherwise I don't know how you've been functioning." I glanced at my father, who gave me a nod of camaraderie. I wasn't crazy after all.

As my body slowly healed—with the help of Dr. Denton, acupuncture, and craniosacral therapy —I often wondered why my dad had been so keen to keep me away from the emergency room. Did he worry that if the ER workers—trained to view the world as, well, an emergency—had seen me in that state, there was a good chance I'd have been whisked away like my mother?

On the ride home from Dr. Denton's office, I gazed out the window at the passing flowers, so bright on that rare day of Michigan sun. "Thank you," I said, turning to my dad. By which I meant: for believing me. He looked surprised. "You're welcome," he said. By which he meant: I knew better this time.

We're all marked by stories—bad decisions, missed opportunities, mistakes made in distress. But sometimes, with luck and love, our histories can be transformed into the medicine that makes us whole.

Thank you for being here, dear Beyonders! ❤️ Your comments (and hearts) mean so much to me. I read each and every one.

Dear Jane, thank you for this. Cranialsacral therapy was pivotal in healing trauma for me as I had built a wall around my heart which kept out pain but also love. Healing thoughts your way, Trish

Jane, your writing has made your father real to me. What a mensch. The love and trust flower in each piece. Even the most compassionate and well-intentioned people absorb the certainties of their time. I remember when women were sent away for shock treatments for a problem with no name. It happened more than once to the mother of a friend of mine, whom I loved and admired. I chose the friend so I could be near her mother.