Cindy Lamothe on Motherhood, Grief, and Metamorphosis

Read "A Room of My Own," Cindy's new essay about the arduous reconstruction of the human heart

I first met Cindy Lamothe when I was coming out of a dark health hole during which I hadn’t published anything for years. I was still struggling with lingering symptoms and overwhelmed by the new publishing landscape that faced me. I was a music journalist with a hankering to write personal essays. I so admired Cindy’s writing and nervously reached out to her for insight. She instantly took me under her wing and with her help, I began to find homes for my work. So it’s particularly meaningful to share Cindy’s latest essay here.

Clearly, Cindy is a kind, wise, and generous soul. She’s also a staggeringly gifted writer, able to sink into the emotional muck that dwells inside so many of us and write about it in the most gorgeous, glorious manner. Her words always leave me brimming with hope.

Born in Honduras and raised in America, Cindy currently lives in Guatemala with her ridiculously beautiful son. She writes everything from investigative articles and op-eds to fiction and poetry and personal essays. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Al Jazeera, Vogue, The Atlantic, The Guardian, The Washington Post, Guernica, Catapult, and so many others.

Cindy comes from a mixed background of Latin American and European heritage. She’s currently at work on a memoir exploring her multicultural identity and experience growing up between worlds.

A Room of My Own

“A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind long before it makes words to fit it…”

—Virginia Woolf

My son was nearly four months old when I pushed my small desk that had served as a changing table from our bedroom into the guest room—hanging old photographs on the walls.

There, I thought, a room of my own.

The desk had been a gift to myself meant to commemorate my budding identity as a writer. But three years and hundreds of diaper changes later, the initial intent had long lost its meaning.

My husband at the time was off to India for the next two weeks and I would be alone with our infant along with the growing inadequacy in my throat. I could barely breathe imagining all that could go wrong. By the time I moved the desk, I was rotating nights in our spare room in order to get a few hours of sleep—our baby’s soft nightly coos paired with his unexpected reflux were enough to keep me awake surveilling his every breath. Every evening, when my son fell asleep in his crib, I slipped into our guest room and lied down exhausted and defeated.

Moving the desk would be my act of defiance.

If it could stop being a placeholder for dirty diapers, then maybe I could also stop being a proxy for the person I’d once imagined becoming.

Creating a home overseas was not new to me, but choosing to live in my then husband’s country of birth meant that I would be without community: without a support system during or after pregnancy. This meant that despite transient friends and family who visited every few months, I would find myself immersed in long stretches of solitude.

In the days that followed my son’s birth, I was privy to the steepest learning curve I’d ever experienced. The grueling round the clock feedings and lack of sleep were only matched by my sudden bouts of crying and intense fear that left me reeling by the end of the day. I worried about how to care for a small person. How to become as selfless as I would need to become in order to provide the kind of comfort I never experienced while growing up. I worried the world was too dark, too unpredictable.

No one warned me that giving birth, just like grieving, could shatter you wide open.

None of the parenting books describe this agony of maternal transformation. Or that, apart from sleep deprivation and anxiety involved in caring for a fragile infant, I’d experience a profound loss of personal identity—a violent pulling away from all that is known.

The space I craved was more than physical—it was the room to become, to grow into something beyond myself.

For many years I awoke from life-like nightmares that presented a version of me pregnant and terrified. In these dreams, I was always worried, and even in those rare moments the scene turned happy, I awoke in a petrified state. Since having my son, I haven’t had a dream like this. Maybe it was pregnancy that lifted the veil from the fearing of it.

But I discovered, that if death is like the taking of a limb, in which only time can comfort, then giving birth and becoming a parent is the arduous growth of a new appendage; painful yet extraordinary in its reconstruction of the human heart.

**

It was Virginia Woolf who declared that for a woman to write, it was necessary for her to have a room of her own. In The Waves, she writes: “Let me pull myself out of these waters. But they heap themselves on me; they sweep me between their great shoulders; I am turned; I am tumbled; I am stretched, among these long lights, these long waves, these endless paths…”

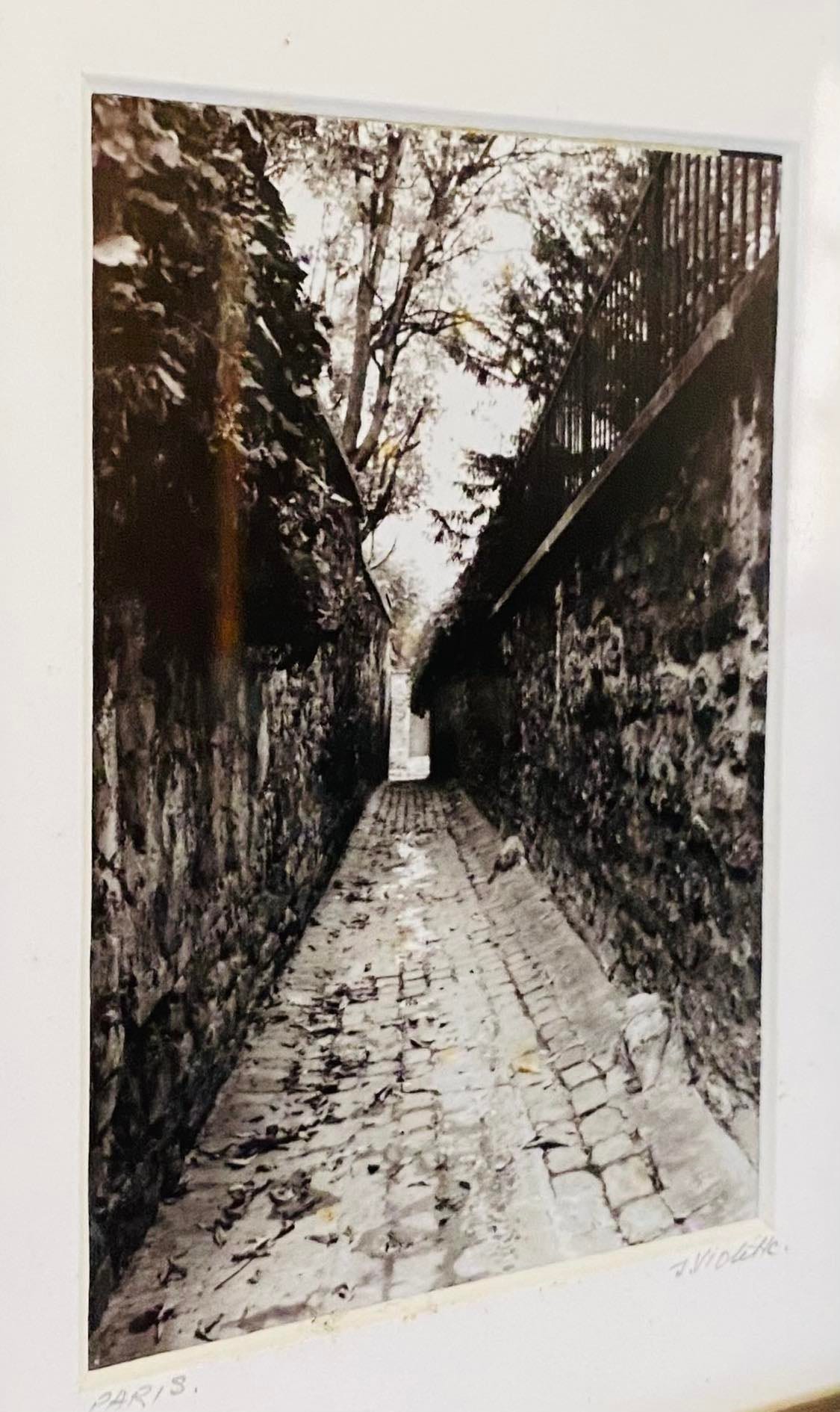

The day I decide to move my desk into our guest room, the impulse is survival. I shove the spare bed to a corner and hang a frame I bought in Greenwich village years ago; a small black and white portrait of a dark alleyway in Paris. I see my twenty-something self step in front of me—her voice in my mind once again, urging me to not conform. You’re still you. For the next hour my son sleeps, I place my fears on pause and hear my thoughts take murmur.

Becoming a mother is not unlike a cocoon we grow into: A way to shed the layers of our past selves and begin the metamorphosis of growing new eyes and skin.

I once read that the universe is all dead or alive—we can choose to see it as either. And the only difference is our faith that it is one or the other. Because as humans, this small truth is our superpower—the ability to transcend even science or pure fact; to find the reason behind chaos or the chaos behind reason. Who we are, boils down to this decision: Things will always be dead and alive; but it is our choice to believe this world to be a wondrous fulfilling prophesy or a glorious mistake.

**

Slowly, I begin to write about the waitress at the country buffet we visited soon after my brother’s memorial over a decade ago. How she filled my sweet tea to the brim, stared into my grief eaten face, and said “only the good die young.” These brief, kind words from a stranger were enough to hold me for years. A wave distilled into memory.

I type out pages about my brother and the love I held for us both. How my mind became fragmented and lost those first months after his suicide, and how in certain instances, I can still outline the creases and lines of those cracks.

In a room of my own, I write about knowing what it looks like when the earth opens up and shows you her secrets—and how for a moment, brief and stretched over millennia, I can peer into her depths. I listen to Nina Simone and think about community. About the people who share in our grief the way sea animals share the same ocean; how they orbit each other’s lives. A poet once told me that the life of a survivor of suicide loss was circular to an ocean, and there are so many jellyfish that can sting you.

**

After Frida Kahlo suffered her tragic accident with a trolley that left her bedridden for years, she began to paint the object of both her suffering and her freedom:

I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone,

because I am the person I know best.

In the following weeks, I cradle my son in my arms and recall the ripe mango trees in my abuelita’s backyard in Honduras, and how in the evenings I hid my child-body beneath her apron, never wanting to let go. Beneath her safety there were no screaming matches carried into long hours of the night, no slammed doors or punched-in walls to evade. In having my son, I have created a parallel world for my own sad childhood. In a room of my own, I create worlds within worlds until I begin to see myself clearly.

***

I visit a therapist three months after giving birth. Sitting across from her on her maroon sofa, I tell her about the violent crying on the kitchen floor, the hours at night spent surveilling instead of sleeping. I tell her about my brother dying alone hundreds of miles away without me. I don’t know how to live or be who I’m supposed to be, I say. She suggests postpartum depression, anxiety, and complicated grief. I blink back tears and think that like the waitress after my brother’s memorial, the right words at the right time, can be magic.

***

To become a mother, whether biologically or through adoption, is to be obliterated and reconstituted by love—to be emboldened by its dense gravity and space. Having a child was a shock that jolted me open. A gift I didn’t know how to receive. And in recreating this life to add my son, I’ve been made undone and grown new eyes to see; in the way that love unfolds the deepest parts of you, lifting out corners that have grown dusty from lack of use.

Before motherhood, I didn’t understand how chaos and calm could coexist within a person. I didn’t understand that the space I craved was more than physical—it was the room to become, to grow into something beyond myself.

Staring down at my baby’s small smiling face, I can live in the present. I’m not asked to strip myself away to be enough—I can show up for us each day, fully and flawed. Whether sitting still watching my son sleep peacefully in my arms or spending another evening fighting back tears, I learn to take everything in. Like my weathered desk, I can hold the foul and the beautiful equally, making art from both.

What I know now is that we are all built from twirling molecules—each a universe unto itself. Each in their own orbits, spinning furiously—creating a body—creating a mass of light.

Tell me…

Do you have something you return to, like a mantra or physical practice or some reminder, that helps you hold both “the foul and the beautiful” aspects of life?

I am a psychologist who's practice is called About Motherhood. It is my life work and I have been doing it for about three decades. It was started because when I became a mother, huge parts of me were lost, and there was no language except a “ what's wrong with me” inadequacy. I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the subject, and found my way out through my firm belief that someone who loved her kid as much as I did was NOT inadequate. Slowly I designed a practice that teaches mom's to deconstruct social messaging that is deeply internalized, over generations, across societies.

All this to say...Cindy Lamothe, my deepest bow to you; for your inner work to find that love is the only way out, and your fantastic ability to language your journey. I would recommend this article for every mother. Thank you🙏🏽.

I keep this small tint of items from childhood and teen years mostly photos and old movie ticket stubs. But always a favorite image of this friend and I-- because it was timeless and I wanna hold onto that memory forever