A Life in Books (and other wonderful things) with Joanna Rakoff

Thoughts on what makes a "Best Book". Reviews of The World After Alice, The Sequel, Exposure, Run Toward the Danger. And more!

Hi wonderful readers! It’s Joanna and I’m back with my monthly ramblings on what I’m reading and thinking about. Let’s get into it!

A few months ago, a stranger on Instagram scornfully suggested I lack discernment when it comes to books. Her angry—vitriolic, even—outburst stemmed from my innocuous endorsement of a novel I’d liked. Not loved, actually. But liked enough to think others might enjoy, perhaps even more than had I, for despite my admiration, this novel wasn’t exactly…what I want in fiction. And so when this DM popped up—“you just love EVERYTHING”—I laughed out loud. Because, you see, I actually loathe a large percentage of the many, many books that land on my porch each week, along with the works of many much-lauded, much-loved authors. I am the person who gave THE KITERUNNER a scathing review in a major publication. I do not love everything. Not even close. But I do appreciate many types of things and I do love books for different reasons, and my love can stem from different criteria.

I was thinking about all this last week, when the New York Times dropped its list of the hundred best books of the current century (so far). Leading, of course, to outcry from every corner of the Internet about who was and wasn’t on it. The list, as most of you know, is the result of a poll sent to five hundred writers, including me. And I suspect that many found it as excruciating a task as did I. How exactly to select ten of the hundreds of books that have radically affected me in the last twenty-five years? Books that have changed my life in different ways, changed the way I see the world, myself, my work, the very notion of literature? I’ve loved so many, of such different styles and intentions, written from such different perspectives, with such different relationships to the reader. What criteria should one use in compiling such a list? Should I be thinking about diversity, first and foremost? Should I scan my journals to jog my memory of books from the early Oughts? Or scour my bookshelves? Or just jot down those books that I still think about, every day, years, decades after reading them? And what about the books I love despite a heightened awareness of their flaws? (Yes, you, The Goldfinch. You could have been about 150 pages shorter, friend.)

In the end, I employed a combination of these techniques. I jotted down a list, then took a long walk to think my way back through the years; I sifted through my million books and flipped through my million notebooks. The titles I ultimately submitted, I knew, held very few books that would make it onto the Times list. My choices, I knew, were too “small,” to use that industry term that persists, despite its misogynist slant, deployed to describe novels confined to the domestic sphere, or those that slip into the daily experiences of one mere woman, novels fueled by explorations of emotional minutiae and decisions with the capacity to shatter or save low numbers of lives. My choices, too, leaned toward the comedy of manners and social realism. And–getting back to that commenter–they were unified purely by my own highly specific, personal sensibility. I did not attempt to choose books that I knew the world had deemed important. I chose books that I thought important for the world. Was this the right approach? I don’t know. But it made me think, much about an important question, one I thought about constantly as a younger writer, but which had, perhaps, slid to the recesses of my consciousness in recent years: What do I want in fiction and memoir?

My conclusion: A controlled, confident, singular narrative tone and style. An urgency, which makes itself apparent through the narrator’s restless, searching eye—pursuing its subjects to the depths of their needs and desires and self-deceptions—and through, too, the complexity of language, the engagement, on a word by word level, with the societal forces that invisibly guide our every choice, our every move. Which brings me to this month’s reading, all of which magnificently fit my criteria.

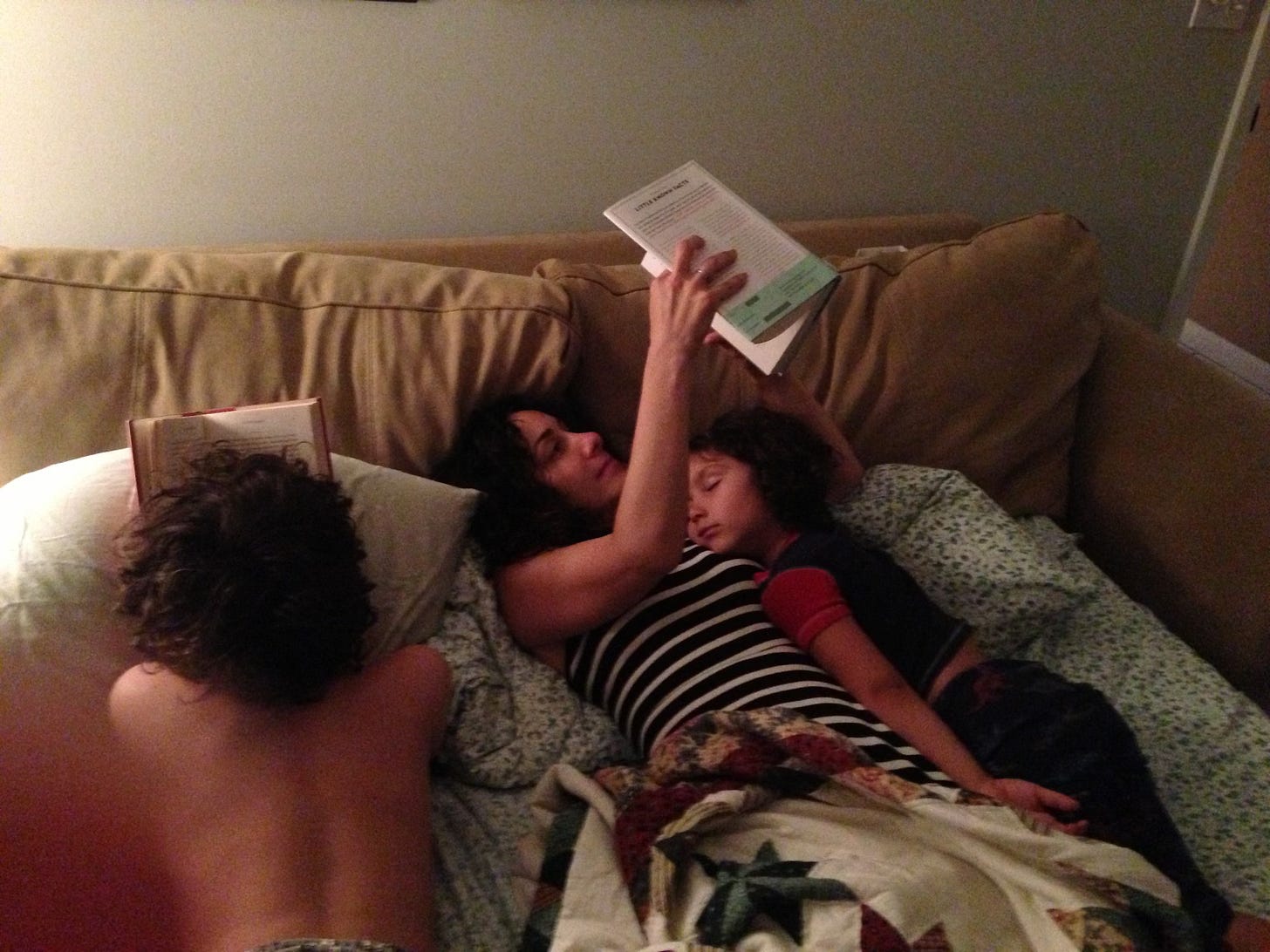

THE WORLD AFTER ALICE, Lauren Aliza Green

Because of certain events in my family’s history, I often sidestep novels—and films, and plays, and everything— about family’s torn about by the the death of a child. (If you were in the Landmark Sunshine when I saw RABBIT HOLE, I’m sorry if my wretched sobbing prevented you from hearing the final fifteen minutes of the film.) But this debut novel was sent to me by someone who knows my taste to a tee—it’s a little uncanny—and so I cautiously picked it up and…couldn’t put it down.

Set in Maine and New York in the very recent past, this is a big social realist novel, in the tradition of Gallsworthy and Gaskell, which elegantly and shrewdly examines the fractures at the heart of a haute bourgeois New York family, in the aftermath of their older child’s suicide. But the magnificence of this novel–which reminded me of a favorite from last year, Andrew Ridker’s HOPE–is in the telling. Green puts together sentences with an urgency reminiscent of Bellow and has devised an omniscient narrator that calls to mind Forster, in its appealing mix of empathy and wry humor. I loved it and I admire it, and have been recommending it to everyone I know.

Lauren just wrote this gorgeous essay for Beyond about marriage, adultery, and grief—how they intertwine in our plots and our lives!

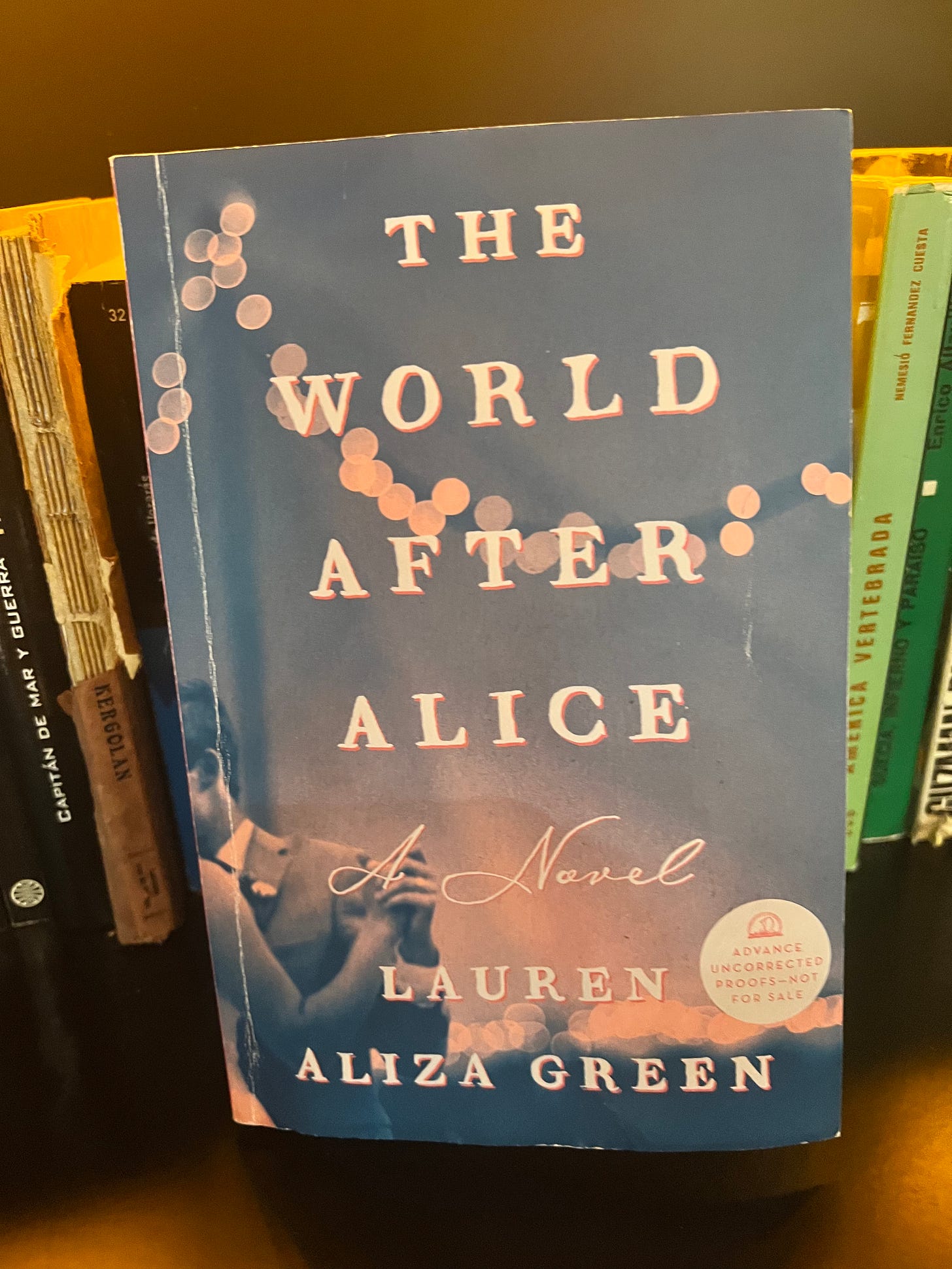

THE SEQUEL, Jean Hanff Korelitz

This dark, glorious, utterly unputdownable novel won’t be out until October, but I want to tell you about it now so that you’ll have time to read her previous novels, which vary dramatically from each other in plot and milieu, but are united by Korelitz’ lovely, Whartonian style, sly humor, and finely calibrated observation. You might start with ADMISSION, my Korelitz gateway drug or YOU SHOULD HAVE KNOWN. Or THE WHITE ROSE or THE DEVIL AND WEBSTER (a campus novel, one of my favorite genres). They’re all so, so good.

If you know Korelitz, chances are you know her from her last novel, THE PLOT, to which this new one serves as a sequel, picking up a year after the conclusion of the last. That novel was kind of a blockbuster and found Korelitz–a writer of incredible range and intelligence–a vast new audience. And this one, I suspect, will hit even harder. At the risk of telling you something you already know: THE PLOT concerns a character of heartbreaking familiarity to many of us: a literary novelist, product of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, etc., who published a bildungsroman right out of the gate, then kind of…lost the thread (sometimes, I fear this me, friends; and I know I’m not alone). Many twists and turns ensue, but, basically, he steals the (great) plot of a students’ (bad) novel, becomes a sensation, meets the woman of his dreams, and…in case you haven’t read it, I’ll end there. All you need to know about this new one is that it begins with that Dream Woman, who turns out to have many secrets of her own, to say the least, and it is, in many ways, a gloss on Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels, to which Korelitz alludes, playfully, throughout the text.

EXPOSURE, Ava Dellaira

Agh, have you ever had the experience of reading a novel and then, in the days, weeks, months that follow saying to your sister or spouse,, “my friend sat on gum at her wedding/met her boyfriend on the subway/accidentally burned off her eyelashes when lighting the stove.” Only to realize, mortifyingly, that it was not your friend that sat on gum, but A CHARACTER IN A NOVEL YOU RECENTLY READ? A novel that wove you so tightly into the texture of its universe, your mind turned its characters, its scenes, into some semblance of reality.

You have, right? It’s not just me. (Please say yes.)

This was my experience with EXPOSURE, the first novel for grownups from Ava Dellaira, a seasoned YA author, which magically spins some of the thornier issues of our time–consent, sexuality, maternal responsibility, gender roles, cancel culture–into a dark, subversive comedy of manners, which will surely be compared–it comes out in September–to THE BONFIRE OF THE VANITIES. The novel begins, in 2004 Chicago, with a bang: A UChi sophomore runs into one of her students–she teaches writing at a nearby high school–outside of class, a handsome, commanding, magnetic student to whom she’d felt–and tamped down–an attraction. The two begin a brief, whiskey-fueled affair and…maybe we should leave it at that. Let’s just say that the novel picks up a decade or so later, when that student is a grown man, trying to break into the film industry, and that the novel–written in crisp, energetic prose–tracks back and forth in time, slowly unraveling the many mysteries at its heart, and raising unsolvable ethical quandaries along the way. Novelists: This one, for me, offered a master class in structure.

RUN TOWARDS THE DANGER: Confrontations with a Body of Memory, Sarah Polley

If you’re a bookish girl of a certain age you know Sarah Polley as the star of Road to Avonlea, her character a stand-in for L.M. Montgomery, the revered creator of Anne of Green Gables. If you’re a girl of a slightly older age–like me–you know her as the unacknowledged star of Atom Egoyan’s Exotica, the stand-in for the viewer, a normal girl keeping up the appearance of normalcy as her family dissolves in tragedy. As an actor, Polley radiated both a fierce intellect and a quiet warmth and something that I want to call bravery, or perhaps strength. All qualities that imbue her work as a screenwriter and director of films like WOMEN TALKING, her adaptation of Miriam Toew’s devastating novel, and the heartbreaking AWAY FROM HER. Friends, I am a fan.

And so it was no surprise that RUN TOWARDS THE DANGER could be described using all the adjectives I’ve employed above. Structured as six long, intersecting essays, the memoir takes its brilliant, bombastic title from the instruction given to Polley after a brutal concussion effectively shuts down her life as a mother and screenwriter, an idea–or metaphor–threaded through Polley’s nuanced, measured examinations of her years as a child actor–in which she was frequently placed in danger–and her mother’s untimely death, and, perhaps most poignantly, the various ways her body has betrayed her, through illness and pain. Claire Dederer, a few years ago, described the best memoirs as “an intellect working through a problem, and taking the reader along.” I can’t think of a more apt way to describe this breathtaking search for meaning and understanding of not just Polley’s own singular life but her place in the world, and the way that world has shaped her, and the ways she can use that life to repair it.

(I really loved critic Lauren LeBlanc’s interview with Polley in Vanity Fair.)

READING NOW:

I just spent nearly three weeks in Spain–my first visit!--and became borderline obsessed with the history of Barcelona, in particular, so I tore into Colm Toibin’s riveting, if dated, HOMAGE TO BARCELONA. I’m also deep into Ella Berman’s twisty thriller BEFORE WE WERE INNOCENT, loosely based on the Amanda Knox phenomenon.

SOME SHORTER READS:

What could be better than Catherine Newman on menopause?

One of the best takes on the Alice Munro revelation, from excellent novelist Bethany Ball.

, a favorite writer of mine, asks this question of herself and friends, and I’ve been thinking about the answers for days.AND ALSO:

The Amazon series MY LADY JANE is perfectly written–by genius Gemma Burgess–and acted, and very, very iconoclastic, in terms of storytelling. A delight.

My fifteen-year-old, Pearl, introduced me to the podcast Binchtopia, and all I have to say is: LISTEN. And also: Don’t start from the beginning. Just pick an episode that sounds interesting and dive in.

Okay, friends, I’ll see you again in August! I hope you’re all finding time to rest and relax this summer and sending love, Joanna

In case you missed Joanna’s June recommendations, you can find them here:

May I add to your recommendations two foreign writers whom I love and find, especially one of them, Andrei Makine, a fascinating French author born in Russia. The other is Elena Ferrante (a pseudonym), well known to this country's readers with her The Neapolitans novels, the best one for me, My Brilliant Friend. M. b., Makine is not the bestselling writer and not for everybody's taste, but he is more interesting for everybody who wonts to step beyond well-known situations and characters. His style is poetical, tender, reflexing and brilliant. Background of his novels is political because his novels mostly about Soviet or modern Russia. His best novels for me: Dreams of my Russian Summers (Goncourt Prize) and The Woman Who Waited.

Love book recs!! Sorry about the trolls. So tired of the trolls.