Rebecca Makkai

On #MeToo, the blinkered nature of whiteness, and how to shave 1,000 words out of your chapter.

Thank you to everyone who is sharing Beyond on social media, in their own newsletter, or forwarding it to friends and family, subscribing, liking, commenting, and recommending. Your support means so much to me.

Each interview takes about twenty to thirty hours of work, from prep to final edit, often more. If you’re able to become a paid subscriber, deep gratitude. Your contribution allows me to do more interviews as well as keep a roof over my head. If you’re not able to become paid, I get it. Very happy to have you here either way!

Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

I can’t remember how I first came to hear of Rebecca Makkai and her beautiful books but I do remember reading her first novel, The Borrower, when it came out. The enchantingly eccentric road trip of a librarian and her ten-year-old charge instantly stole my heart. And the exquisite writing bowled me over. Next came The Hundred-Year House a witty (Rebecca is nothing if not uproariously funny) and joyous delve into an artists’ colony that’s held in a haunted house. And, once more, the exquisite writing bowled me over. This was followed by Music for Wartime a collection of gorgeous, thoughtful short stories, many inspired by her family history. And, yes, the writing is exquisite. Then, of course, The Great Believers, which was a Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award Finalist, and received the ALA Carnegie Medal. It explores the AIDS epidemic in the mid-and-late eighties in Chicago. Exquisite. Rebecca glories in a big cast of characters, complex plots often covering great swathes of time, humor, tenderness, frankness, and profound insight. While her characters are often in precarious situations, she treats them all with care.

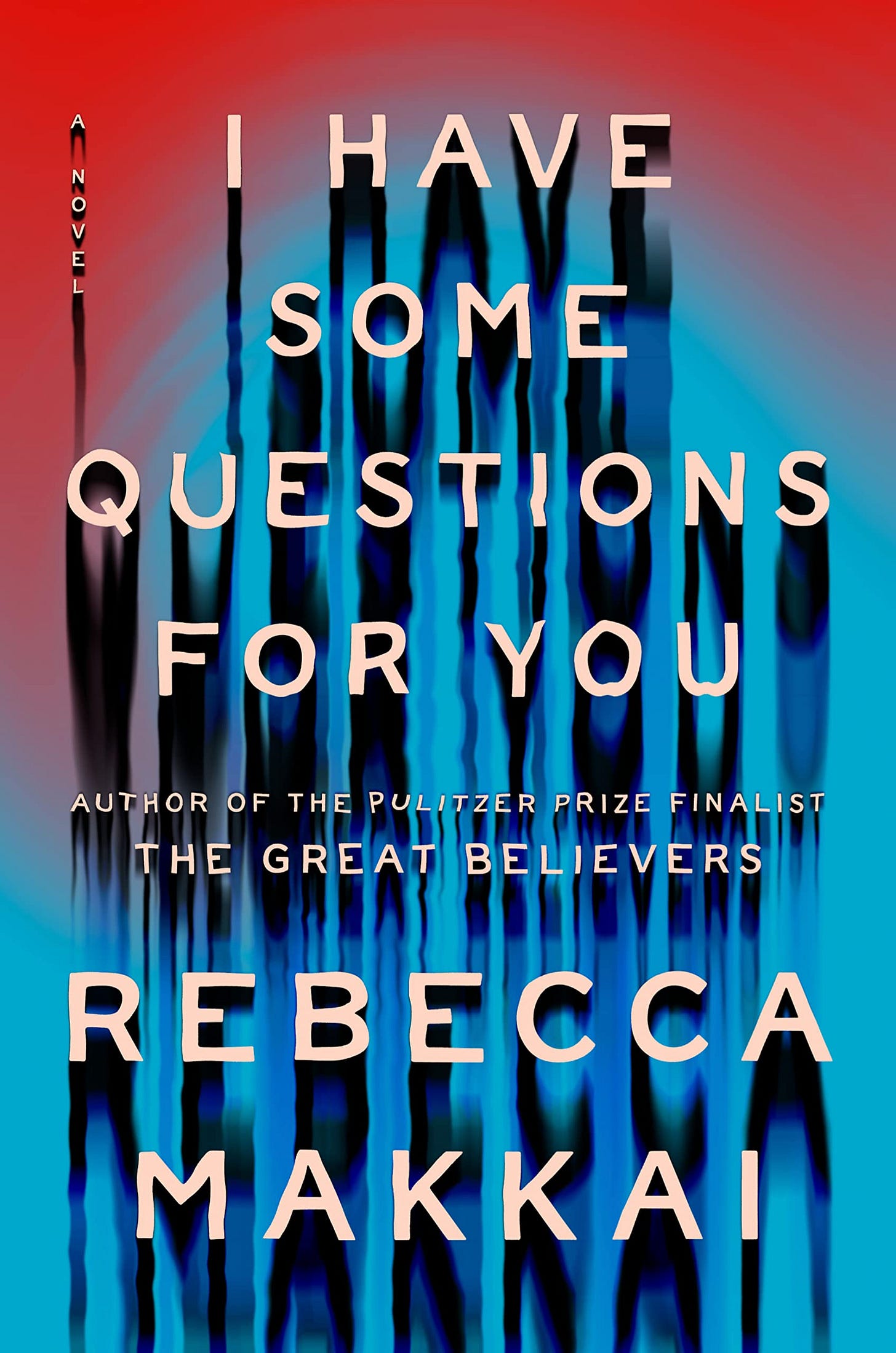

All of this and more is present in her latest novel: I Have Some Questions For You. Set in New Hampshire in 2018, successful podcaster Bodie Kane has returned to her former boarding school, Granby, to teach a class on how to create your own podcast. One of her students decides to focus hers on the murder of Thalia Keith who attended the school back in 1995 when Bodie was also a student and who was briefly her roommate. A twenty-five-year-old Black man, Omar Evans, who had worked as the athletic trainer was convicted of the crime but it’s now clear to Bodie that the evidence was flimsy—and that she may know more about the murder than she realizes. As her student begins investigations for her podcast, Bodie launches her own including speaking with former classmates, connecting with a vibrant online community pushing for Omar’s release, and reckoning with her own memories. Beyonders: It’s so good! (Yes, the writing is exquisite!)

In addition to writing brilliant books, Rebecca is on Twitter generously offering up daily prompts to get writers writing. She’s also obsessed with Zillow, which she explains here (on her own fantastic Substack: SubMakk), and provides humorous takes on some alarming houses. And after her father, a translator, died in Budapest at the start of the pandemic, Rebecca launched Around the World in 84 Books where she promises to circumnavigate the globe by reading one important book from as many countries as she can.

Rebecca’s work has been translated into twenty languages. Her short stories were included in Best American Essays an impressive four years in a row. She’s on the MFA faculties of Sierra Nevada College and Northwestern University, and is Artistic Director of Story Studio Chicago. She’s also an all-round lovely, kind, and deeply funny human.

Throughout the book, you list various murders of young girls and women. It’s quite potent. Compiling these must have taken a fair amount of research. As did, I would imagine, researching how Thalia’s murder might have convincingly happened. What sort of toll did all this research and then the writing have on you?

Similarly, to my last book, The Great Believers, where I was doing so much really intense research on AIDS and loss, I always had somewhere to put the emotions that came up. I had this vessel, this book, waiting for all that sadness or anger. Often, when people go through something hard, art is a great way to therapize that, to get that out of them. There's an even more direct line when you're already creating a work of art: you do research that is then feed straight into that. We want that emotional energy that the research triggers but there's this pretty healthy mechanism to immediately turn around and use that information rather than sitting there and going “well, now I can't sleep.” I have something to pour it into.

That makes perfect sense. Your book is about women’s bodies: what is done to them: murder, rape, groping and other such violations; and also what women do to our own bodies: starving, self-harming, diminishing. Mixed in throughout is also kindness and pleasure. Amongst the predators are a few male students and a trusted teacher. Standing up to these men is both futile and dangerous because this behavior is accepted as normal and girls are taught to shrug it off. With the #MeToo movement, this began to change. Where do you think things stand now with women and our bodies?