Jo Salas on Becoming a Novelist Late in Life

Read "Irrepressible Words" Jo's new essay on her journey from suppressing her literary ambitions in her teens to publishing her first novel in her sixties and her second in her seventies.

I first met Jo Salas here on Beyond and was impressed by her thoughtful, tender comments, and by how she conveyed so much insight and emotion in so few words. So I wasn’t surprised when she managed to pack oceans of brilliance and precision and sweet, aching tenderness into this essay she wrote for Beyond and do so in such few words—but I was absolutely bowled over by it. I’m guessing you will be, too.

Jo takes us on a writer’s journey from childhood determination to later in life publication—and all the being-a-human stuff that arises in between; a journey in which many of us will find at least one piece of ourselves. I certainly did!

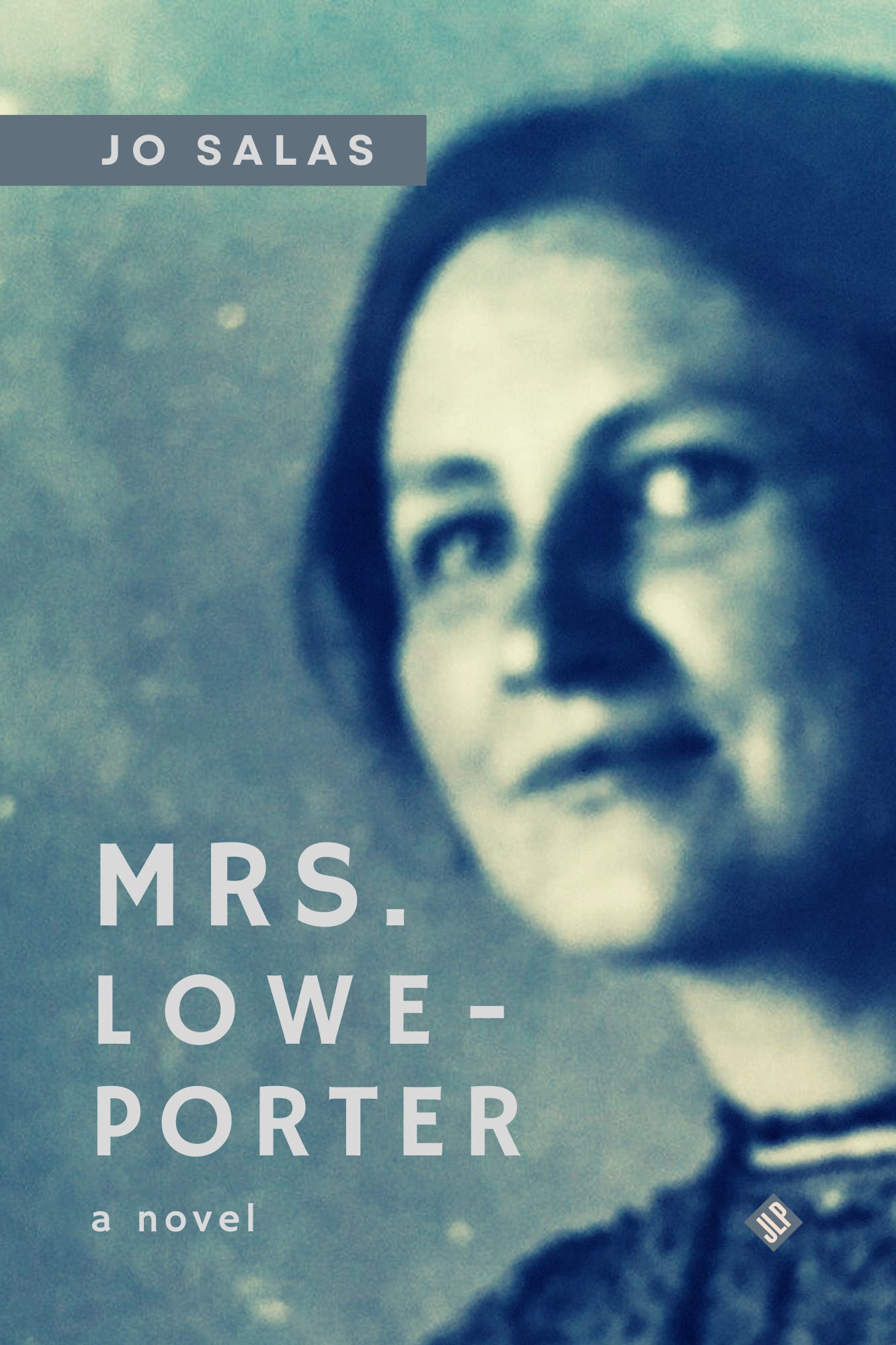

Jo is a New Zealand-born writer living in New York's Mid-Hudson Valley. Her second novel, Mrs. Lowe-Porter, which she writes about here, will be published in February 2024. Her first novel, Dancing with Diana, was published in 2015. Jo is also the cofounder of Playback Theatre and has authored four books and numerous articles about this original form of story-based improvisational theatre, including Improvising Real Life: Personal Story in Playback Theatre.

Irrepressible Words

After I read Little Women, at eight years old, it dawned on me that I had a claim to be called Jo. Josephine was my middle name. And I was the second of four sisters, just like Jo March. So, I became Jo, and have been ever since.

My new name underlined the urge to write that was within me even then. In my teens I wrote passionately, fluently, sometimes with whimsy or wit. I thought I’d do this for the rest of my life.

Then, at the age of 17, I fell in love, and decided, under the weight of centuries of conditioning, that my new boyfriend was a better writer than me and therefore I should focus only on supporting him. He didn’t make that demand. He didn’t even know about my literary ambitions. Within four years we were living in a remote shepherd’s cottage in England, helping the farmer with his animals. My new husband wrote short stories while I looked after our baby and washed nappies in cold water.

Writing came back to me about seven years later, when I started chronicling the theatre work we had started together after we returned to the States, living by then in a small town in upstate New York. Again I felt that fluency and joy. I had readers: my impulse to write was met by the eagerness of others in the theatre world. I wrote my first book to support the growing number of people who practiced the theatre method we had created. It’s now in 10 translations, from Portuguese to Nepali.

I continued to write and publish nonfiction—but then fiction writing came knocking at my door until I finally opened it. My first published short story, “It begins to tell,” appeared in a local arts-and-entertainment magazine. I had the unusual experience, for a writer, of face-to-face comments from people who’d read it. “I’ve always wondered if writers really make it all up,” said a friend outside the grocery store. “And now I know they do!” She meant that I was (at that time) not an old woman like my protagonist, so the story must be invented.

It was. But, like most stories, it grew from a sliver of real life. Years before, a friend told me that her elderly mother had vetoed her husband joining her in the nursing home where she’d lived for several years. The poignance and mystery of it stayed with me. What could have led a decorous old lady at the end of her life to refuse her husband’s wishes? I had no idea, but my imagination built a narrative around her action—a young jazz pianist, a censorious husband, a lifetime of suppressed yearning.

I wrote story after story, usually prompted by a kernel of fact, like the first one.

And then, a novel. To entertain myself while I painted my kitchen, I listened to Tina Brown reading her book The Diana Chronicles. An anecdote stuck in my mind: Diana at 15, before she was a princess, revealing her extraordinary empathy in a school trip to visit disabled people.

My novel Dancing with Diana was published in 2015—about a boy in a wheelchair who dances with Diana for five minutes and can never forget her, interwoven with the story of Diana’s tragic last day. My small publisher made a beautiful book but did nothing to promote it. I tried, with little success.

I did not plan to write another novel, until, in my mid-sixties, I was drawn into it by the life of the translator Helen Lowe-Porter. Helen was a remarkable person: the translator of the Nobel Prize-winning German novelist Thomas Mann, a mother of three, and a gifted writer in her own right who strove all her life to fulfill her artistic vision. She was not helped by having a distinguished husband who outshone her and betrayed her. His mid-life affair with a very young family friend broke her heart and changed the direction of her life. Helen’s story, I felt, was a classic women’s predicament.

Helen was also my husband’s grandmother. I had access to personal reminiscences and many of her papers. I worked on the novel for years, reading Helen’s letters and essays, visiting the street in Oxford where she’d lived and her beloved cottage on a Maine island, talking to other family members. It wasn’t going to be a biography: I wanted the freedom to imagine and invent, while also honoring this extraordinary woman whom I’d never met. She became fully alive in my mind: brilliant, meticulous, witty, self-deprecating, loving.

When the dispiriting business of querying agents had not brought an offer, I attended a writers’ conference in New York where aspiring writers could meet agents seeking new submissions. The writers—recognizable with their anxious eyes and manuscript-laden bags hugged to their sides—far outnumbered the agents, younger, smartly dressed, relaxed, chatting with each other. I joined a small group where one agent read aloud the first page of a manuscript and three others would comment. I held my breath as a stranger read my words. One agent shrugged. “Competent. But I’m only interested in contemporary fiction.” Another said: “No one wants to read about writers, especially failed ones.”

Like my main character, I was by then getting old. I had no more patience for the agent game. But I wanted my novel to find publication. I wanted Helen Lowe-Porter to be known, after being in Mann’s shadow all her life. Even recently, in Colm Tóibín’s highly detailed biographical novel The Magician, Helen, whose 22 translations sealed Mann’s reputation in the English-speaking world, is not mentioned beyond a single disparaging line.

I met a “publishing Sherpa”—a generous, savvy woman who guides writers like me to find the right path to publication. She connected me to an independent literary press. The fiction editor wrote that she was thrilled I’d decided to accept their offer.

After years of “no thank you” or no response at all (the industry standard) I could hardly believe it. Helen’s grandson and I broke out the champagne.

And now my novel, Mrs. Lowe-Porter, is finished, ready for its readers, exactly one hundred years after her first Mann translation appeared. For me, it’s a significant milestone. Will there be more novels? I don’t know. But for now, I’ve kept faith with my name.

Tell me…

What did you give up of yourself due to societal conditioning? What have you regained? Any dreams that have carried you from childhood to now? What has helped you keep your faith? What moved you about Jo’s beautiful story?

Hello I am now working on the three stories in my heart that I can’t bear to see go to the grave with me... I just turned 60 this past August. I wrote my first poem in the first grade and then started writing more sophisticated projects each year until my work was so polished that I was constantly accused of having plagiarised it from someone else’s perspective (always said I was too young to be such a good writer rather then being such a talented writer who was so young.) But never❤️

For a long time, I gave up on any ambitions behind motherhood and marriage. I was raised Mormon and taught that my place was in the home, supporting my husband in his dreams. Many years, one religious exodus, and one divorce later, I am finally daring to believe that I (at 42) can grow up to be whatever I want. I so appreciate Jo’s story of later-in-life success as a novelist. I hope that will be the story of my forties!