Hello Friends! It’s my birthday! To help me celebrate, if you’re not already, please consider becoming a subscriber. If you’re a free subscriber, please consider becoming paid. If you enjoy Beyond, please share this post, or click on the heart at the end and leave a comment. All of this helps spread the word, and the more support Beyond has, the more interviews I can do and the more guest contributors I can run. Thanks heaps for all your generosity and kindness in 2022. I look forward to adventuring though 2023 together!

The first post I read on Jillian Hess’ enchanting Substack Noted concerned Agatha Christie’s exercise books. My mother adored Agatha Christie. She owned every single one of her books (upwards of eighty) and had read each of them enough times that their spines were cracked and the pages bent. Somehow seeing Christie’s handwriting, large, sloppy, and often illegible though it was, brought my mom back to me—and I found myself close to tears. She would have loved learning about Christie’s “splendid ideas” and “practical details” along with all the lovingly researched context Jillian provides.

I immediately became a subscriber. Jim Henson, Oscar Wilde, Frieda Kahlo, Jim Morrison, and James Baldwin are just a few of the note-takers Jillian explores. Each week, she diligently and devotedly offers glimpses into the inner workings of some of our most creative minds via their notebooks—be they exercise journals, friendship albums, or good old-fashioned diaries. She also provides insight, context, and commentary into the world in which the note-takers lived.

An English professor at CUNY, Jillian has been driving around America, visiting archives and filling up her own notebooks for over two decades. Her wisdom and tenderness for her subject shines through.

I’m happy to share one of her most popular newsletters with you: “Read Like Virginia Woolf.” No need to say more because Jillian describes it all beautifully herself!

If you enjoy her newsletter, which I feel confident you will, you can subscribe here.

Read like Virginia Woolf

"That’s the real point of my little brown book…that it makes me read —with a pen—following the scent."

For Virginia Woolf, one of history’s greatest literary minds, to read was to converse, to hunt, to emulate, to savor. Reading was transcendent. It was a love affair.

She confessed,

Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.1

Best known for her novel Mrs. Dalloway, Virginia Woolf was also a prolific essayist and an important publisher — and a lifelong note-taker. For the most part, Woolf took notes while writing non-fiction. She also gathered background information for her novels and other subjects she was studying.

“The great season of reading,” Woolf suggests, “is the season between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four.” I’m not sure I agree, but I did start keeping reading notebooks in earnest at around the age of sixteen (more on this later). To prove her point, Woolf proposes we look at our early notebooks:

Let us take down one of those old notebooks which we have all, at one time or another, had a passion for beginning. Most of the pages are blank, it is true; but at the beginning we shall find a certain number very beautifully covered with a strikingly legible hand-writing. Here we have written down the names of great writers in their order of merit; here we have copied out fine passages from the classics; here are lists of books to be read; and here, most interesting of all, lists of books that have actually been read, as the reader testifies with some youthful vanity by a dash of red ink.2

So let us take down some of Woolf’s notes to see what we can learn from her magnificent collection of 67 notebooks.

Make your own notebooks

On her 33rd birthday, Virginia and her husband Leonard decided to buy a printing press and start their own publishing house. Hogarth Press was born in 1917 and offered a sanctuary for artists, removed from the pressures of the marketplace. The Woolfs went on to publish their own works as well as that of their friends. Hogarth has the distinction of publishing the first U.K. edition of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland.

Virginia Woolf had been binding her own books since the age of 19; operating a printing press was an obvious next step. Once the Woolfs set up their press, Virginia fell in love with the monotonous, time-consuming work of type setting. She told a friend, “You can’t think how exciting, soothing, ennobling and satisfying it is.”3

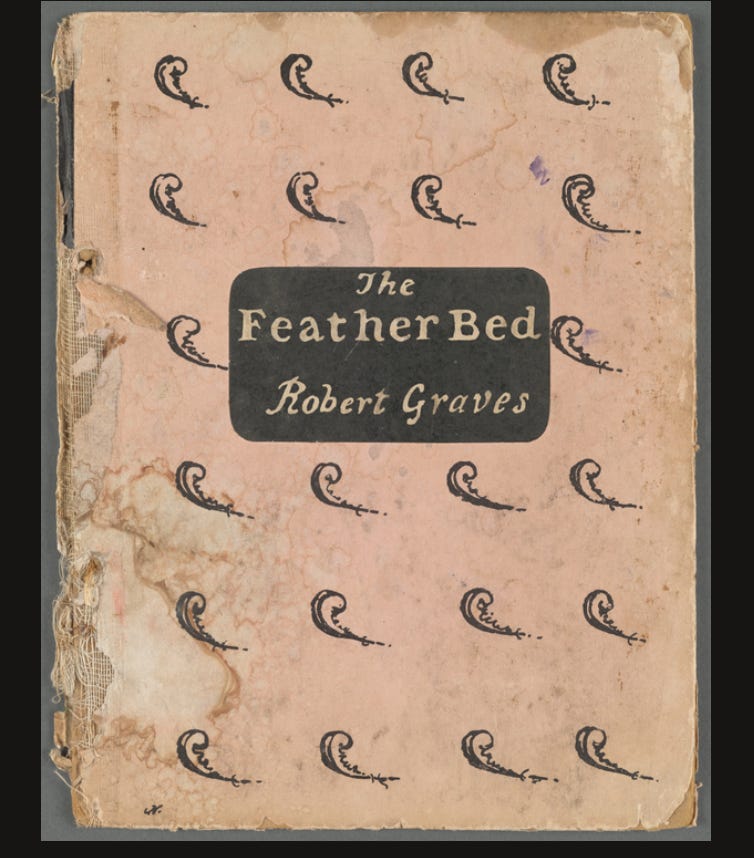

Sometimes, she would make notebooks for herself out of leftover bits from the Hogarth Press’s books, such as this 1929 notebook (notice the purple smudges that match the color of ink she used for part of this notebook):

This particular notebook contains notes on William Cowper and Mary Wollstonecraft in preparation for articles Woolf wrote in the autumn of 1929.

Another notebook, bound with Hogarth Press scraps, covers projects from the 1940s including Robert Fry: A Biography, as well as readings on women and war. Woolf includes several tables of contents throughout, including on the front cover and the spine.

Personally, I’ve been making my own notebooks for the past 6 years or so, and I highly recommend it. If you care as much about paper and formatting as I do, you can’t leave those decisions to someone else!

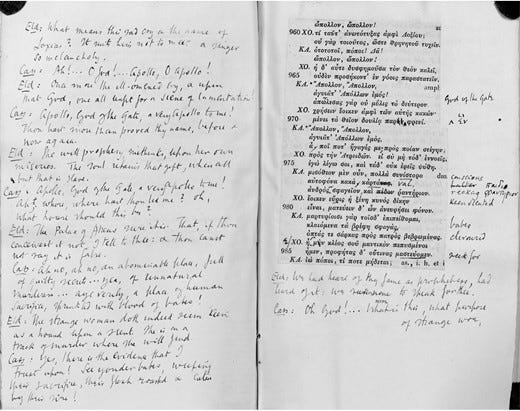

Make your own edition: The Agamemnon Notebook

Just as she made her notebooks, Woolf made her own edition of Aeschylus’s play Agamemnon. She took scissors to a 19th-century edition of the Greek text, pasted the pages into a notebook, and surrounded the cuttings with an English translation and notes. Woolf explains the process:

I am making a complete edition, text, translation & notes of my own – mostly copied from Verrall, but carefully gone into by me.4

This is how the scholar Yopie Prins describes the notebook:

Unpublished and unauthorized, her private “edition” was less a translation than a transcription, to which Woolf added a few variations with occasional marks and remarks in the margins, commenting on passages of interest or defining Greek works that she had underlined and looked up in the Greek-English dictionary. After several months of trying “to make out what Aeschylus wrote” (Diary 213) and “master the Agamemnon” (Diary 25), Woolf was pleased to proclaim, “I now know how to read Greek quick (with a crib in one hand) & with pleasure” (Diary 73).5

Use colorful pens

Woolf loved her pens, which she saw as accomplices:

To begin reading with a pen in my hand, discovering, pouncing, thinking of theories, when the ground is new, remains one of my great excitements.6

In 1929 she was writing with gold and green pens. She wrote notes on Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals with a gold pen, which she “didn’t think quite as good as ... [her] old one.”7 But she loved her green pen, which she described in a letter as

a new lizard green pen, a slippery sort of pen, golden, laxative, loose-tongued8

A bit more on color

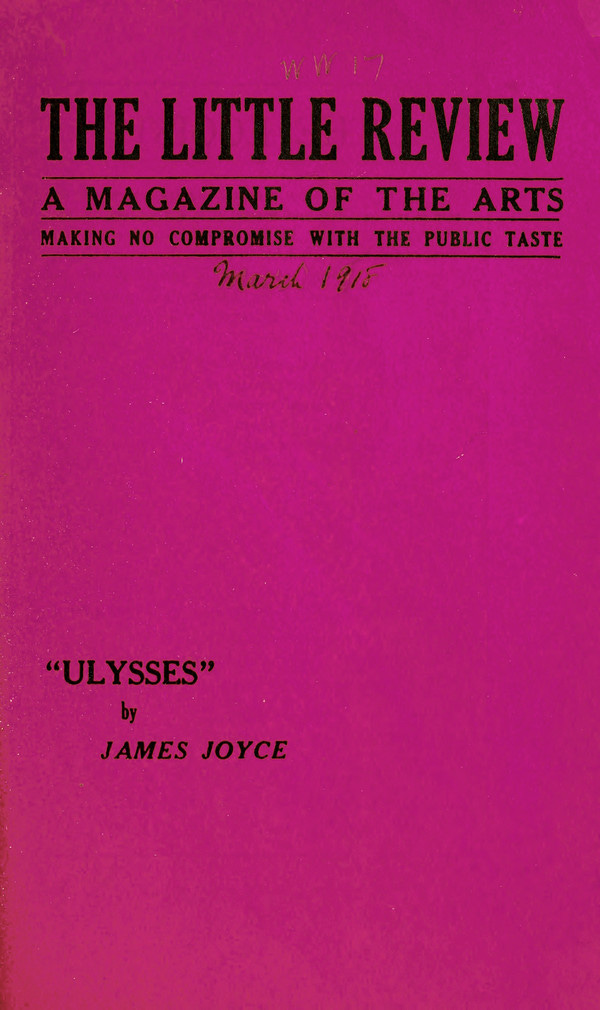

In her notebook titled, “Modern Novels,” Woolf records notes on Joyce’s Ulysses — along with a mysterious list of colors.

Order of Ulysses I — claret red

II — pale blue

III — orange

And so on. It took my a while to figure out what these colors refer to. And then I realized that she was indicating the exact shade of the cover for each installment of Ulysses in the The Little Review.

Perhaps this is redemption for those of us who organize our bookshelves by color?

Follow the scent (make indexes)

Woolf would create her own index to whatever books she was reading by marking important page numbers and a summary of information to be found there. Often these summaries included quotations or Woolf’s own reflections. She describes this method of reading as though she were on a hunt:

That’s the real point of my little brown book…that it makes me read —with a pen—following the scent.9

She wasn’t just writing out quotations, she was summarizing and analyzing as she read.

Here are a few bits of Woolf’s notes, as far as I can make them out. All of them are on Robinson Crusoe:

53 after the wreck “I never saw them afterwards”…

62 Sudden vividness — an incident…

80 The diary repeats everything, as if to make [illegible]…not a cranny for disbelief to enter.

102 being glad I was alive — a mere flight of common joy

(Woolf is a beautiful writer, which makes it all the more frustrating that her handwriting is so difficult to read. I did my best. Sigh)

Read like a novelist

As a reader, Woolf was attuned to the choices novelists made.

The quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiment with the dangers and difficulties of words.10

Woolf imitated authors in her copy books. She also wrote notes on how authors depicted their characters, crafted scenery, or used colors to convey mood. Some examples as transcribed by Brenda Silver (who also struggled to read Woolf’s handwriting):

“The difference between rare gold coins & flecked with gold,” she comments on an entry on Antigone, “‘flecked’ gives the horses ear shape” (XLV B.2)

…an entry headed “Colour in Poetry” analyzes images from Shakespeare and Herrick: “Herrick. The [?tinselled] stream — using [?tinselled] to express moonlight on water” (XXXIII, B.4)11

In short, Woolf honed her craft as a novelist while reading.

Woolf ends “How One Should Read a Book” with a gorgeous description of the joys of reading.

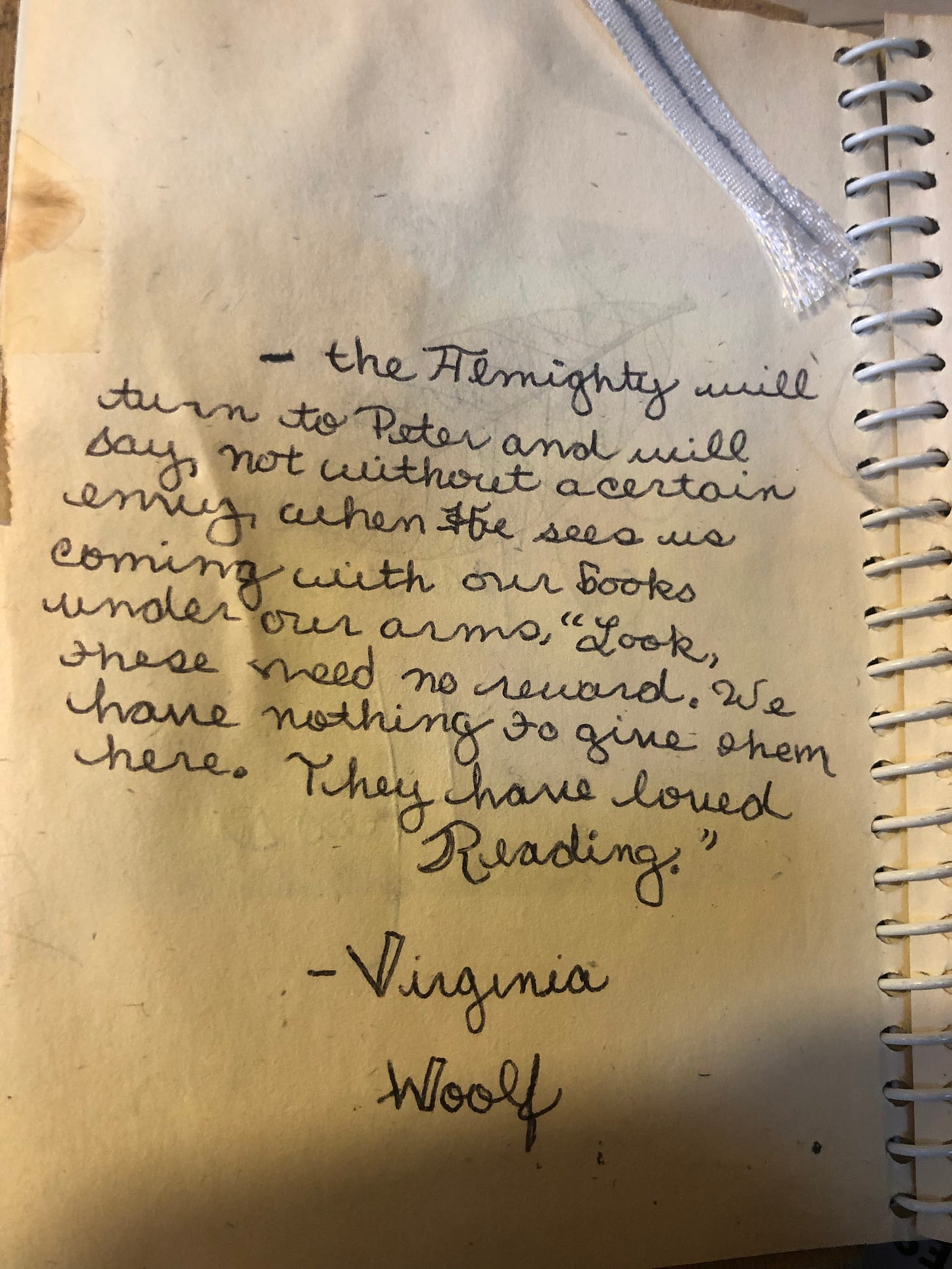

I have sometimes dreamt, at least, that when the Day of Judgement dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards — their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble — the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”12

I loved these lines so much when I read them at the age of 16 that I wrote them on the first page of my very first commonplace book — or what I then called a “Reading Log:”

I hope you enjoyed this tour through Virginia Woolf’s notes (with a brief stop to admire my teenage scribblings). You can support this newsletter by liking this post, hitting subscribe, or leaving a comment.

Till next week,

Jillian

Hi Jane. First, the most important thing:

Happy Birthday!!

I love your substack for so many reasons- and today it’s like a present you give us on YOUR birthday.

Thanks for the gift!

I was busy painting in my studio and decided that instead of reading I would listen to today’s entry with Jillian Hess.

(how great to use the audio feature if my hands and eyes are busy with something else - a nice way to not miss your newsletter)

I enjoyed so much hearing about Virginia Wolf’s notebook - all the many details!

I love that Jillian hunts and excavates for this gold. I’ll have to subscribe to her substack.

(I did)

I am not a journal keeper or notebook maker.

I am a list-maker and a Post-it note stacker.

However, I still related so much.

It had me smiling to hear how similar what Jillian does (and Virginia Wolf did) in notebooks is to how I approach making a painting.

It caused me to look at my painting in a way I hadn’t before. Nifty!

Happy birthday!! I hope your readers enjoy this piece!