Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

Gayle Brandeis is a marvel of kindness, mischief, wisdom, humor, staggering talent, rule breaking, nature loving, dog doting, and, as her email signature indicates, gentle rabble rousing. Lucky for us, all of this and more manifests in her writing.

Gayle and I were always bumping into one another in various social media writers’ groups. I almost always knew a post was hers because of the magical way she sees the world. In fact, I wrote about it here. Gayle’s writing is also magical—though it often explores hard even brutal subject matter, she does so with great care and hope. In one way or another, she’s using her voice to amplify other voices while turning the rule book of writing on its head.

Her novel in poems, Many Restless Concerns, centers the voices of hundreds of girls and women murdered by Countess Erzsébet Båthory between 1585 and 1609. The Book of Dead Birds, winner of the PEN/Bellwether Prize, explores bigotry, human trafficking, and intergenerational trauma.

Perhaps best known, her memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide gently yet unflinchingly braids Gayle’s childhood health struggles with Crohn’s disease and her mother’s peculiar celebration and encouragement of this; transcripts from her mom’s documentary on her own and her family’s health issues; the role of silence in her family; the challenge and beauty of marriage; and her mother’s struggles with delusions when Gayle is pregnant with her third child. Days after Gayle gives birth, her mother hangs herself.

Gayle has written nine books: three nonfiction, five fiction, and one poetry. Her essays have appeared in the New York Times (one of my favs!) and The Guardian, amongst others. Her poems have appeared in Split Lip Magazine and The Nervous Breakdown, amongst others. And her short stories in Literary Mama, amongst others. Gayle teaches in the low residency MFA programs at Antioch University and University of Nevada, Reno at Lake Tahoe. After decades on the West Coast, she’s recently returned to Chicago with her husband and youngest child. She also periodically teaches workshops so if you see one advertised, I’d suggest signing up!

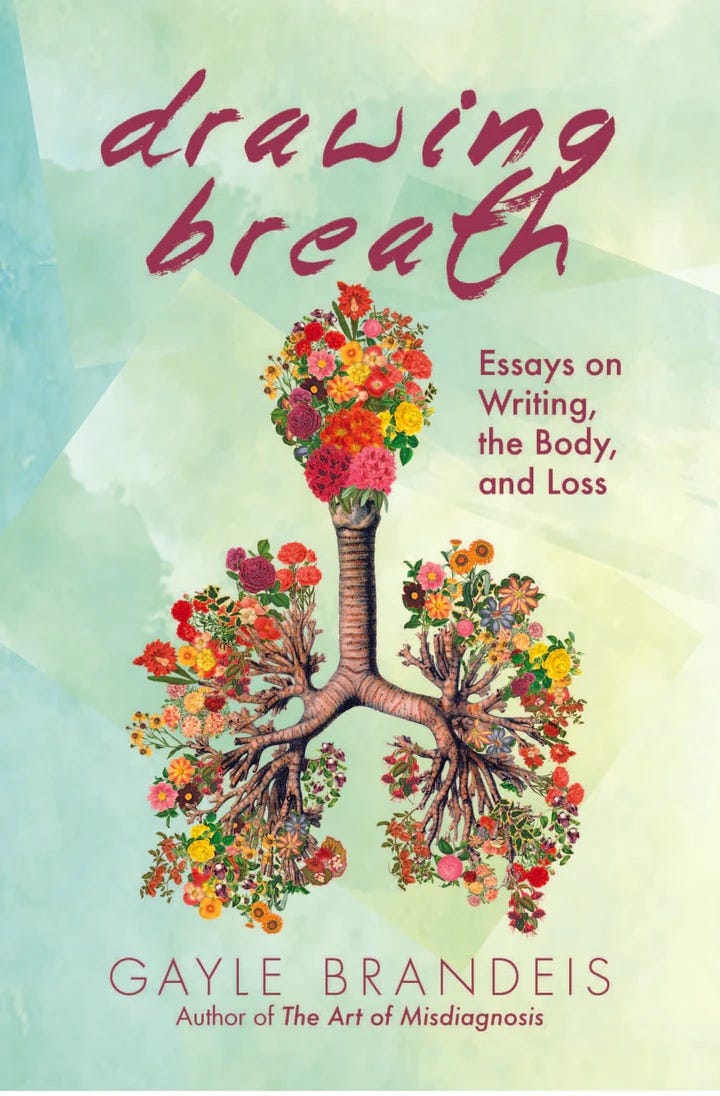

We chatted about the wonder of going to seed, reclaiming our bodies from the patriarchy, and her gorgeous new book Drawing Breath: Essays on Writing, the Body, and Loss.

In one of my favorite passages in Drawing Breath, you write: “I’ve been noticing lots of scatterings in the woods of late, salsify and prairie goldenrod going to seed, their colorful blossoms turned to pale puffballs, those puffballs taking to the wind. I’ve been thinking about how the phrase “going to seed” has been used in such a negative way, akin to “letting oneself go”—why is it so bad to go to seed, when that’s such an act of generosity and hope, sending the stuff of life out so future generations can flourish? Why is it so bad to let one’s self go? Don’t we sometimes hold on to our selves too tightly, not allowing them to change or grow or evolve or show the impact of time?” I get the chills reading that! What inspired this?

Early in the pandemic, I’d gotten really sick and wasn't bouncing back. I started thinking about how as we get older, parts of us fade or fall away. My walks in the woods helped me reframe this from something that scared me to something I could embrace. I could see the natural cycle happening on a day-by-day basis; the woods never looked the same from one morning to the next. I wanted to embrace my own fading, whatever it looked like: whether I was changed by illness or disability. I felt my experience could be like a plant going to seed and letting those seeds scatter to future generations. My own presence in the world didn't need to be as robust as it had been; I was on the downhill slope, but that's not a tragedy, that's part of the lifecycle. And I wanted to see the beauty of that.

Throughout the book you touch upon women’s desire and how dangerous that can be in our society. In particular, women’s midlife desire. You write: “I keep finding more and more stories in which women make big changes spurred by unexpected storms of desire in midlife. Stories of women who discover—or finally let themselves claim— they’re lesbian or bi or pansexual in midlife; stories of women who let desire guide them out of bad situations into the lives they truly want, toward their own most authentic, audacious stories. Midlife desire often comes at a shock to these narrators, likely because such stories hadn’t been told regularly in our youth-obsessed culture.” Can you say more?