Thank you to everyone who is sharing Beyond on social media, in their own newsletter, or forwarding it to friends and family, subscribing, liking, commenting, and recommending. Your support means so much to me. It keeps Beyond growing, which allows me to do more interviews and publish more guest contributors. Deep gratitude!

Intimate conversations with our greatest heart-centered minds.

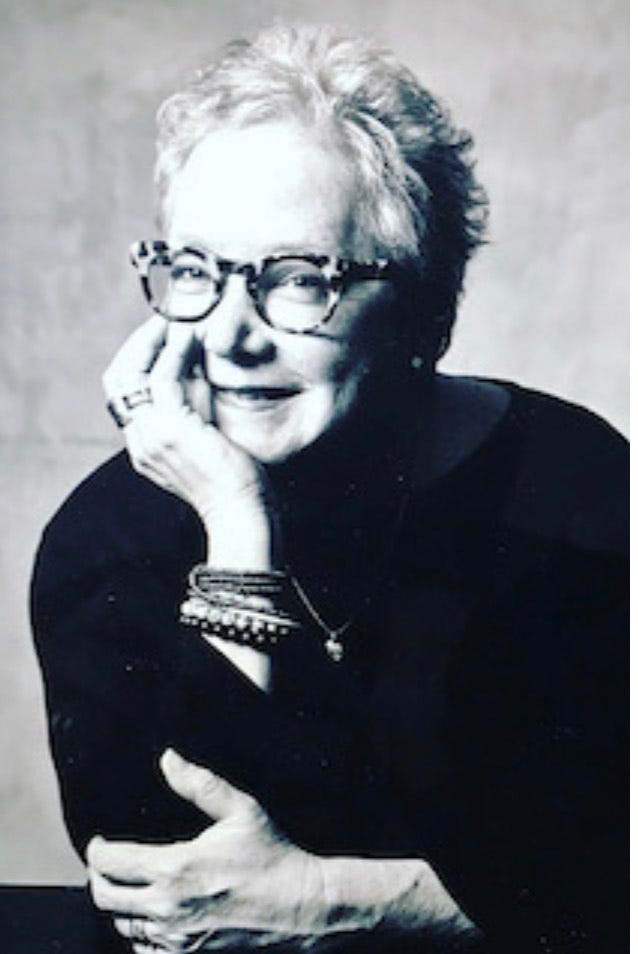

I first became aware of Elissa Altman when my social media feed exploded with rapturous praise about her memoir Motherland: A Memoir of Love, Loathing, and Longing. Who is this Elissa Altman, I wondered as I promptly ordered her book.

Well, Elissa Altman is a multi-faceted wonder. A New Yorker through and through, Elissa first became known as an executive editor for major publishing houses, working on sixteen New York Times bestsellers, following a career as a bookseller at the original Dean and DeLuca. Soon her passion for food as sustenance, healing, and a vehicle for sharing our experiences inspired her to write her own stories. She launched the James Beard Award winning blog (now a wonderful Substack newsletter) Poor Man’s Feast in 2008. Here she writes about love and family and dogs and birding and the complications of having a human body and the intersection of sustenance and spirit—and really good food. Its tone is measured, quiet, gentle, yet celebratory and expansive.

Elissa first memoir Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking was published in 2013, and was pronounced by the New York Times Book Review as “the finest food memoir of recent years.” Next came Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw a sly memoir about tradition, religion, and family expectations.

Which leads us back to Motherland. Nominated for a Lambda Literary Award, a Maine Literary Award, and a Connecticut Book Award, this is a deep dive into Altman's childhood right through adulthood spent navigating a life with a demanding, fragile, often cruel, narcissistic mother. Because it’s written by Elissa, the investigation is tender, mindful, funny, and deeply self-aware. The focus is less about how did this happen to me? and more how do I build a safe and thriving life whilst also tending to a mentally ill parent? When Elissa finally leaves NYC and moves in with her soon-to-be wife Susan in the wilds of Connecticut, her mother calls up to fourteen times a day with all sorts of needs and rarely a kind word—and Elissa must learn to set hard-won boundaries. Yet through it all, Elissa never shakes the primal desire of any daughter: to be loved by her mother, and, in turn, to love and care for her mother to the best of her ability.

Elissa attended Boston University, Cambridge University, and the Institute for Culinary Education. Her essays have appeared in O, The Oprah Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post (where her column Feeding My Mother ran for a year), among others. She lives with her wife of twenty-three years, book designer Susan Turner, in Connecticut and their dog Petey and three kitty cats. She’s working on her next book: On Permission: A Manifesto for Writers, Artists, and Dreamers, coming from Godine in 2024.

We chatted about primal hope, complications of elder care, and owning your own fuckedupness.

You write in Motherland: “Gardening is a contract with hope.” I love that.

Having grown up in Queens, New York, in an apartment, I had no gardening background whatsoever. We were plant killers in my family. I remember my mother having a spider plant—everybody had spider plants in the mid-seventies—and she would forget to water it and it would die. And that was that. So, it was not a thing for me.

When I moved from Manhattan to Connecticut in 2000, Susan had a small house on an acre of land, and the acreage was absolutely flat. Her mother had been the daughter of a subsistence farmer and gardening was her therapy. She made it very clear that if we were going to be living in a place that sun splashed, with no trees and no shade, that we were going to make use of it in a way that Yankees would do. So we built raised beds, and I discovered that I really loved it and arguably had a feel for it.

I also discovered that I really loved growing roses. I'd studied in England for a bit and there were roses everywhere. And I spent a lot of time on Nantucket, and there were a lot of roses there, too. I remembered reading Katherine White’s Onward and Upward in the Garden. She was the first fiction editor of the New Yorker and wrote these amazing narrative books about gardening. In January, when things were really dark, she kept herself going by reading flower and vegetable catalogs. So I found myself doing that.

I wouldn't say that I'm a fabulous gardener, but there's something very therapeutic about having your hands in the dirt and having the dirt under your fingernails and seeing how different things respond in different conditions. It’s been a great learning experience for me. I will never know all there is to know and that's fine.

Gardening is a contract with hope because nobody plants a garden unless they expect to be around for the harvest. I'm a very big fan of the nature and science writer Robert Macfarlane and on an episode of Krista Tippett' On Being, he quoted Jonas Salk as saying that we need to be good ancestors. His definition of that is being willing to plant something to take care of the earth, something that we ourselves may not be around to see. That's always in my mind, too.

You already had such a profound relationship with food. Did gardening deepen it or change it?