David Michie on Obstacle Blessings in Writing — and Life

A massive derailment in David's early writing career led him back to his heart, his homeland, his deep love of animals, and a new and thriving writing career.

The moment I stumbled across

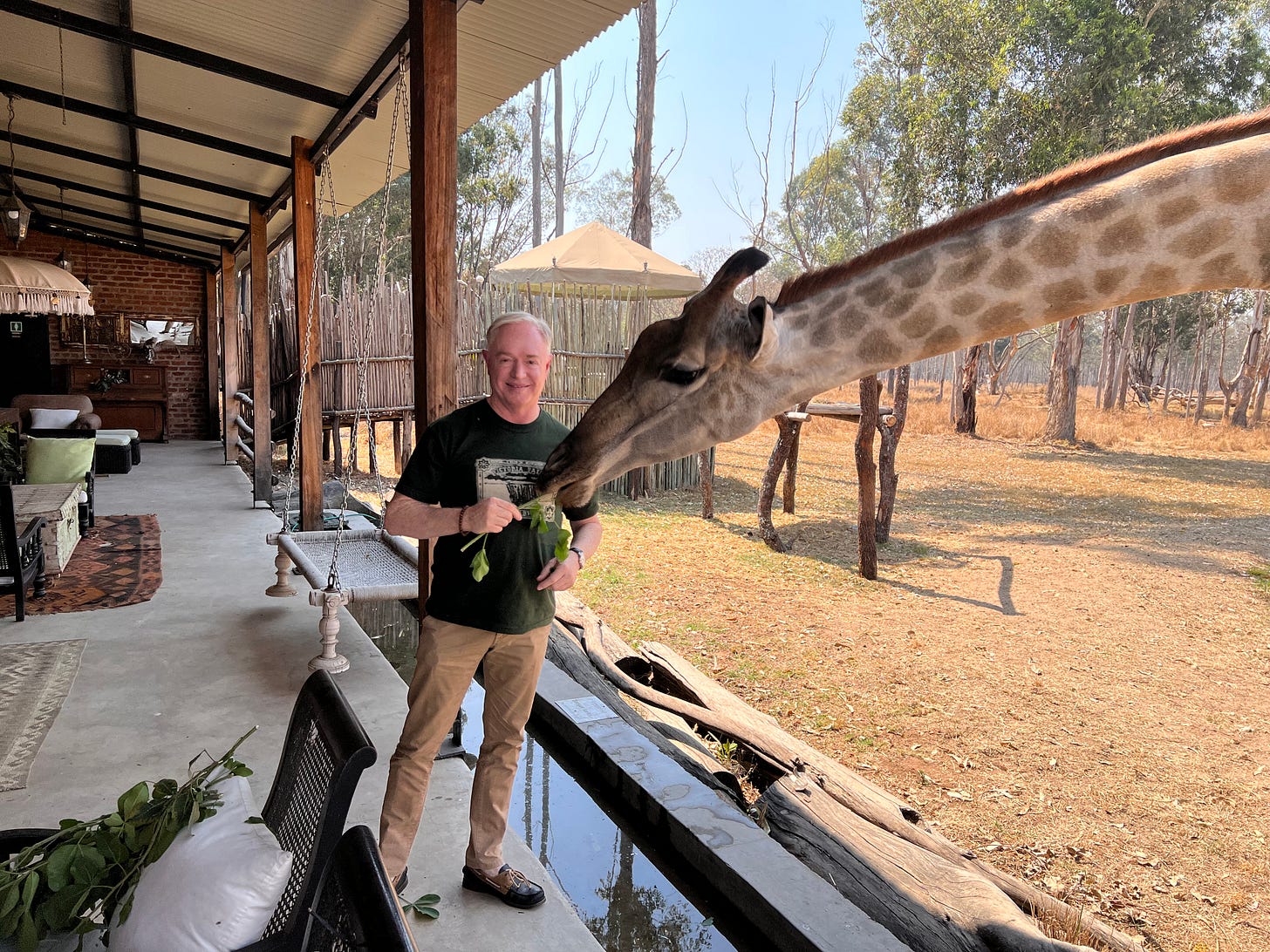

’s newsletter I was smitten. With the exception of one year, from the day I was born I have lived with cats. And I’ve studied Tibetan Buddhism for decades. So I instantly appreciated David’s insightful, practical, and sometimes whimsical approach to sharing Buddhist teachings alongside his adoration of cats!As it turns out, David is devoted to all animals. Born and raised in Zimbabwe, David lived in London for ten years, before settling in Perth, Australia. Starting in 2015, he returned to Africa with groups on Mindful Safaris, which combine his love of animals and meditation with the extraordinary natural vistas of his homeland. He also donates a large chunk his subscription funds to support endangered African wildlife centers including orphaned elephants. Another large chunk supports Buddhist nuns in the Himalaya regions.

On top of all this, David is a gifted writer. In fact, he’s written fifteen books. The Dalai Lama’s Cat bestseller series which has been translated into thirty-five languages, The Magician of Lhasa series, Hurry Up and Meditate, Buddhism for Busy People, and more! His novel Instant Karma is in development for a television series.

I’m so happy David agreed to write this essay for Beyond. It’s tender, wise, funny, and bursting with hope. So much in life goes “wrong.” But what if we looked at these derailments as blessing that we just didn’t yet understand?

Enjoy!

xJane

When an Obstacle is Really a Blessing

Readers who have come across my books usually know me as the author of Buddhist fiction (such as The Dalai Lama’s Cat series and The Magician of Lhasa) and non-fiction (including Buddhism for Busy People and Hurry Up and Meditate). But this wasn’t what I planned for my life as a young man. It only worked out this way because of a massive derailment. Or so it felt at the time.

Like many writers, I was a compulsive scribbler from a young age. My kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Ames, with whom I was secretly in love, was so taken by a poem I wrote aged seven that she had me stand on a chair and read it out to the massed ranks of kids. They were then required to applaud. Was that dizzying acclaim what started it all off, I sometimes wonder?

Poems and short stories in my teen years were followed by my first novel when I was eighteen. By the time I was thirty, I had written ten full length novels, most of which were roundly rejected by every agent and publisher I sent them to. And I queried many. I did receive a few crumbs of comfort – an ‘almost made it’ rejection letter here or doomed agency representation there.

Did this trouble me? Of course! Despite Herculean efforts I was failing to make any headway in my chosen vocation. I never doubted that I was ‘meant’ to be a writer. And not just any writer. A ‘major international best-selling novelist’ was my chosen affirmation. Coming of age in the 1980’s, I bought into the promises of Tony Robbins and Madonna, of Flashdance and the Power of Myth that you could be whoever you wanted to be. I’d even moved from the cultural backwater of Zimbabwe, where I’d been brought up, to London, to usher in this glamorous new reality.

And then finally it happened - or seemed to. I got my first book deal for an expose about spin-doctoring, my day job being in public relations. That non-fiction deal paved the way to me securing the support of Ed Victor, the literary agent more famous than many of his authors, who cruised around London in a Rolls Royce and, whenever I went to see him, seemed to have just got off the phone from ‘Freddie,’ author of The Day of the Jackal. Sitting on the sofa of his capacious office, listening to his wildly entertaining anecdotes about editors on both sides of the pond, for the first time it felt to me like things were about to happen.

And they did. Within months, my thriller Conflict of Interest was the subject of a bidding war between two rival publishers. I still remember being handed the fax saying that Little, Brown had offered a six figure sum when my wife and I returned to the hotel in New York where we were visiting. And along with the tantalizing advance, the marketing section of the proposal contained the spookily precise promise to turn me into ‘a major international best-selling novelist.’ It was thrilling and vindicating all at once.

The wheels of the publishing industry grind slowly. It took eighteen months for Conflict to be published in hardback, and a further year for the paperback edition to come out, which is when mass market sales really kick in. In the meantime, I wrote two further thrillers in the same genre.

Having met and married my Australian wife while in London, after ten British winters we moved to my wife’s hometown of Perth, the warm climate more akin to the one I had grown up in. It was here that we were adopted by the most delightful Himalayan cat. With a lustrous cream coat, charcoal face and clear blue eyes, somewhat wonky on her pins, she belonged to a neighbor but increasingly spent time with us, away from their baying hellhound of a Chihuahua. When we moved house, the neighbor was only too happy to let us take her with us: little did we suspect what an extraordinary literary muse she was to become!

In that pre-digital age unless there was a retail stampede, it took time for sales data to come through. Eventually when they did, sales figures for Conflict were reported as solid but not spectacular. Regrettably, spectacular was needed to match the advance I had been paid.

So, another fax bookended my thriller-writing career. Little, Brown wouldn’t be buying another novel, it said. My editor wished me well. She looked forward to seeing my name rising on future best-seller charts. My writing career seemed over almost before it began.

That fax was, without question, the most devastating of my life. It is one thing to be turned down as an unknown writer – stupid editors! Don’t they recognize potential when they see it? – but quite another to be dumped because of poor sales. The ‘major international best-selling novelist?’ Awakening the giant within? The years of honing my craft, relentlessly exploring all options and never giving up – what on earth was it all for?

I was blindsided and crushed in a way that I never had been. Everything that I’d struggled for had come to nothing. Far from being an up-and-coming novelist, I had been thrown on the trash heap of not-good-enoughs. Never had I felt so humbled, depressed or purposeless.

Two saving graces prevented me from dissolving into a complete pity party. The constant support of my loving wife. And Buddhist classes. I had begun meditating in London for stress management reasons and began going to Dharmas classes soon after getting to Perth. As an animal lover, I liked how Buddhism recognizes the sentience of all living beings.

Of more immediate relevance was the way that the Dharma gently but directly refuted many of my assumptions about the nature of happiness. Did material success really make people happy? Was fame and fortune truly a worthy aspiration? I knew from my time on Ed Victor’s sofa that his most miserable client was also a household name thriller writer.

Buddhism helped me cope with the freefall following that bombshell from London. And given its wealth of powerful and often counter-intuitive ideas and practices, it was the Dharma more than anything else I would talk to others about when socializing. Conversations which sometimes ended: “Is there an intro book to Buddhism you would recommend?”

There wasn’t as it happened. Traditional Tibetan presentations often weren’t aligned to the Western world view. And Western writers who’d ventured into this space, with the best of intentions, weren’t always clear communicators. Which was when the thought struck me: perhaps I could have a go?

I wrote Buddhism for Busy People when I was still only a few years into Dharma practice. My motivation for writing was utterly different from previous books. I wanted, pure and simple, to share my enthusiasm for the life-changing insights I was learning. I had no financial expectations. Buddhism is a niche market – surprisingly few people are interested in exploring the nature of consciousness or of reality, or how one gives rise directly to the other.

I contacted an editor at Australian publisher Allen & Unwin who had published other Buddhist books. To my surprise, she made an offer. And to our mutual surprise, several months after it came out as a paperback original, it had sold in sufficient quantities to trigger a reprint. Months later, another reprint. These were followed by translation deals, a US deal – and a request for me to write a new book.

With a certain inevitability, the storyteller within began questioning if there wasn’t, perhaps, a way to communicate Buddhist themes using fiction? A lot of intelligent, curious people shun non-fiction for their leisure reading, having to deal with far too much of it at work. When I heard that the Dalai Lama once had a cat, it occurred to me that the goings-on in His Holiness’s office might be intriguingly explored through the eyes of a feline much like our own pampered Himalayan. And so began a new chapter in which I evolved into writing Dharma fiction and non-fiction, a sub-genre that a reader memorably described quite recently as ‘a gateway drug to the Dharma.’

What I really want to focus on here is the obstacle. That monumental setback. As I have come to learn from my lamas, the way any event is perceived depends entirely on the mind of the perceiver. And those perceptions are shaped by conditioning, or karma. My feelings at the time were that this was the worst thing that could have happened to me. My feelings, twenty years later, are only of relief.

How lucky was I to be dispatched from a career in which I would otherwise have spent years immersed in imagined worlds of corruption, duplicity and evil? Is it possible to do this for decades without it having some kind of effect on your mind? Ed’s household name thriller writer seems like a case in point.

Instead of that, I have spent the past 20 years discovering that external reality is more ephemeral and mind-dependent than I ever suspected. That we ourselves are not so much passive receivers of what’s ‘out there’ as active creators of it. So, if it’s happiness we’re after, the very best thing we can do is change the movie we’re projecting by taking control of where it’s coming from – our minds. What a rare privilege to have the opportunity to explore this! And in so doing I have had a sense of returning to a path followed in previous lifetimes, and to a broader perspective in which that the season of mainstream thriller writing was, in fact, a temporary aberration.

One of my precious lamas, Zasep Tulku Rinpoche, sometimes talks of ‘obstacle blessings’ which come in many guises. He cautions against being overly reactive when apparently bad things happen, and interpreting everything according to our present, narrow perspective. The Chinese folk tale of the lost horse is the classic example. An old man loses his horse to the wild and when his fellow villagers come around wailing he just says, ‘We’ll see.’ His horse returns along with a few horse friends he picked up along the way. The villagers are happy – if somewhat envious. He just says, ‘We’ll see.’ Attempting to ride one of the wild horses, his son is thrown off and breaks his leg. The villagers wring their hands, despondently. ‘We’ll see.’ The imperial army comes around recruiting able-bodied young men. His son is exempt. And so on.

All of us, especially us sensitive, creative flowers, are prone to seizing the significance of things, concretizing them, imputing patterns where they don’t necessarily exist and heading inexorably towards full-blown catastrophe. I pass on the ‘obstacle blessing’ concept as one of Buddha’s many opponent practices from which we can all benefit. A different way of looking at whatever may be troubling us and allowing for at least the possibility that it may turn out not to be such a bad thing – even if we can’t figure out why just yet.

These days I am able to fulfil my life’s mission which I see as transmission. I return annually to Africa, leading groups on Mindful Safaris. I no longer see Zimbabwe as a cultural backwater so much as a place of unique reconnection. It’s not only the extraordinary animals and people who inspire me. I have also stumbled on revelations of ancient symbols and spiritual practices with direct links to India that have never before been explored. It is one of the great joys of my creative life to share these discoveries with readers on Substack and, in time, a new book.

I am not a major international best-selling novelist. But I have come to see that as the goal of a frail, egotistical creature desperate for a form of validation of questionable worth. My current reality, on the other hand, is one of authenticity and fulfilment. And in the most intriguing of ways it seems to have brought me around the full circle.

That poem I composed for Mrs. Ames in kindergarten was about a witch, a cat and a transcendent state of enchantment. It seems I had to spend forty years traveling the world and getting side-tracked to find my way back to what was in my heart all along.

⭐️ Beyond is a reader-supported publication with the goal of bringing as much light as possible into this world of ours. If you value my work and would like to support it, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you!

This was exactly what I needed to read this morning. So much of the information coming at us with a firehose is telling us to believe in ease, success, and fame, which -don't get me wrong- are all lovely, but life is always punctuated with the hiccups of obstacle. I can't say I'd willing repeat the bigger challenges in my adult life, but I'm surely grateful for them. I also wonder, if I fought them less as they arose, how might things (or I) have turned out differently? Thank you, David!

Obstacle blessing is the story of my life too. What an inspiring read!