A Life in Books (and other wonderful things) with Joanna Rakoff

Ah, the Nineties! When Joan Didion was considered a lightweight and novels about women were dismissed as "small"!

Hi again, and happy fall, wonderful readers! This is the fifth installment of this column and I thought it might be a good moment to ask: Is there anything you’d like to see in it? For those of you just joining me for the first time, let me explain that this monthly feature of BEYOND is really just a chronicle of what I’m reading—and loving (I don’t have time or energy to chronicle books I’m hating, which also feels a bit pointless)—sometimes with explanations of why I picked up this particular book or my relationship with that particular writer. You can find a bit more explanation from both me and Jane here.

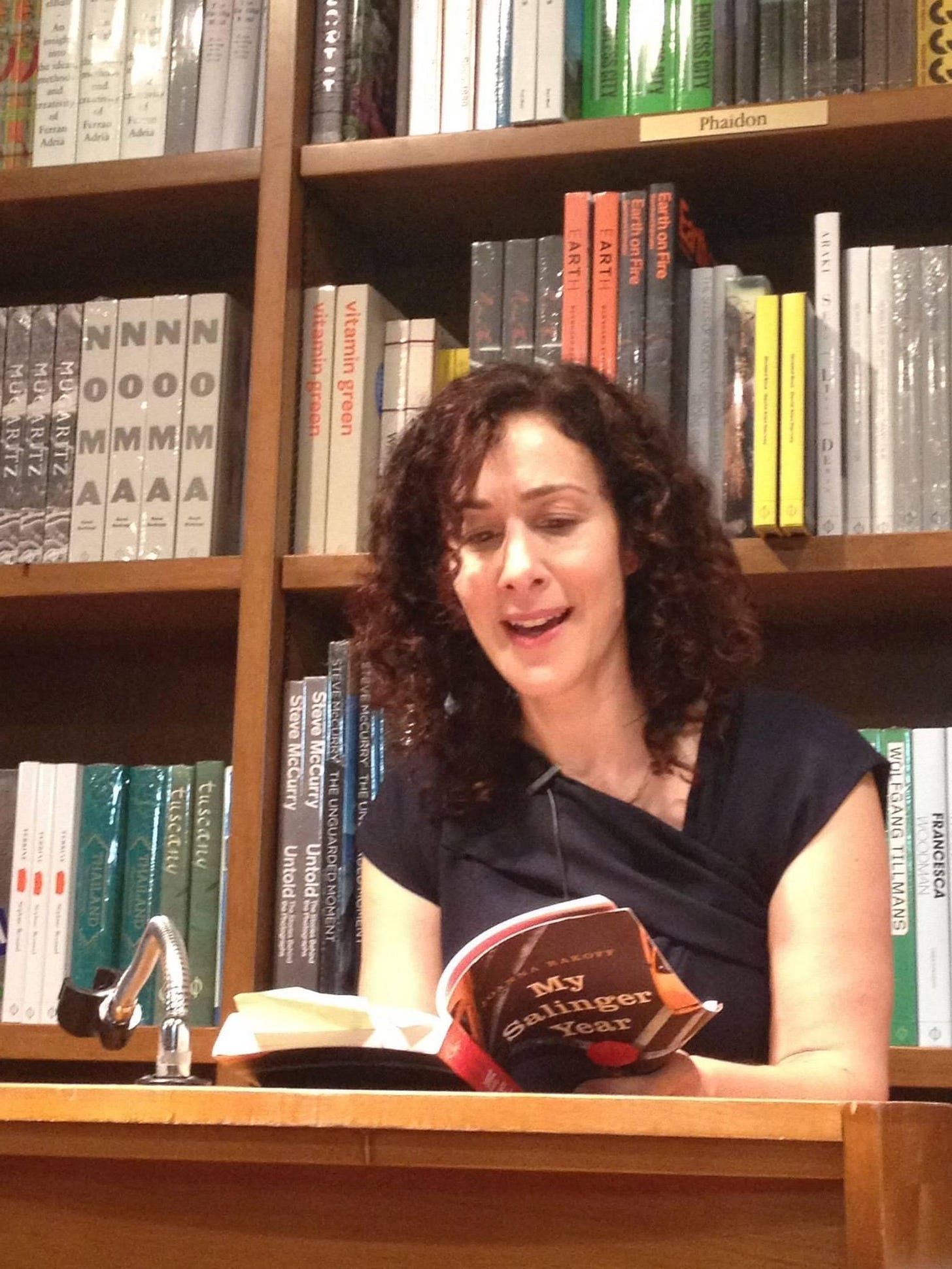

This month, I’m thinking a lot about time, for it seems to be passing more quickly lately. Back in June, a collectors’ edition of my most recent book, My Salinger Year, came out, in celebration of its tenth anniversary, and though in many ways that decade has slipped by in a heartbeat—perhaps accelerated by the pandemic—this landmark has led me to think, much, about the ways in which the world has changed since 2014, the ways in which we think differently about stories that center on women’s daily lives. When I first began work in publishing—during the time chronicled in My Salinger Year—I often heard such tales dismissed, with a knowing wave of the hand, by agents, editors, critics, as “domestic novels” (insert eyeroll meant to connote, “no lasting impact on culture” and/or “will sell a few thousand copies”) or “small books,” (shrug that implied “unimportant” or “for the ladies”). Even at the time, this wasn’t really true, in terms of the publishing end. Plenty of “domestic” fiction had won Pulitzers and climbed the bestseller list and morphed into cultural juggernaut. But the runaway success of, I don’t know, Marilyn French’s The Women’s Room or the critical enthusiasm for Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, instantly considered a classic, or Alison Lurie’s Pulitzer for Foreign Affairs somehow had no effect on conventional thinking in publishing or the literary world.

At parties or meetings or in any sort of intellectually-oriented milieu, I hesitated when asked my favorite books or writers. Should I say Laurie Colwin, Diane Johnson, Dawn Powell, Jean Rhys? Writers whose work chronicled the lives of women, their days at the office and the groceries they picked up on the way home and the cats they tenderly fed and their methods for staying sane in a fundamentally insane world? And risk a condescending smile as this Paris Review editor or that FSG bigwig took a drag of his cigarette and silently dismissed me as a silly little lady entertaining myself with the literary equivalent of bonbons? True story: At one such party, I named Joan Didion as a favorite writer, and a would-be novelist said, in short, “she writes nice sentences but her work has no social or political relevance. I mean who cares about this rich bitch walking across Central Park eating a peach.”

In the weeks surrounding publication of the collector’s edition, I did a bunch of interviews in which I was asked, over and over, why I thought the book had struck a nerve with readers, particularly in certain countries (the UK, India, Australia, Korea, France, all of Eastern Europe), and my answer, of course, was: I’m not entirely sure. Before the book came out, my publisher told me, over and over, that My Salinger Year was a “small book,” with a “limited,” audience, that really only young bookish women in New York—that is almost a direct quote!—would pick it up. And I believed them, for I had resisted writing the book, actually, out of fear that the story was too small, too specific, lacking in the elements of necessary for social importance: war, men, etc. My publisher, of course, was wrong. And their wrongness, back in 2014, strikes me now as archaic, as a relic of certain patriarchal ideas about art that have largely been smashed. Or one patriarchal idea: That stories of women’s lives—inner and outer—hold little importance, should be considered entertainments rather than literature, that such stories are not central to our understanding of the world itself, and necessary for us—for all of us—to make sense of every minute of every day.

After I finished those interviews, I found myself filled with regret that I’d failed to state this knowledge, with clarity and force, that I’d instead offered up my usual “Oh, gee, my little book? Who knows why so many people read it? How crazy is that?” And so I’m correcting that here, and welcome your thoughts on it, and your stories related to it. And here, now, are four very different books which deeply investigate girls and women’s lives, looking at the social and political and economic forces that shape them. They are anything but small.

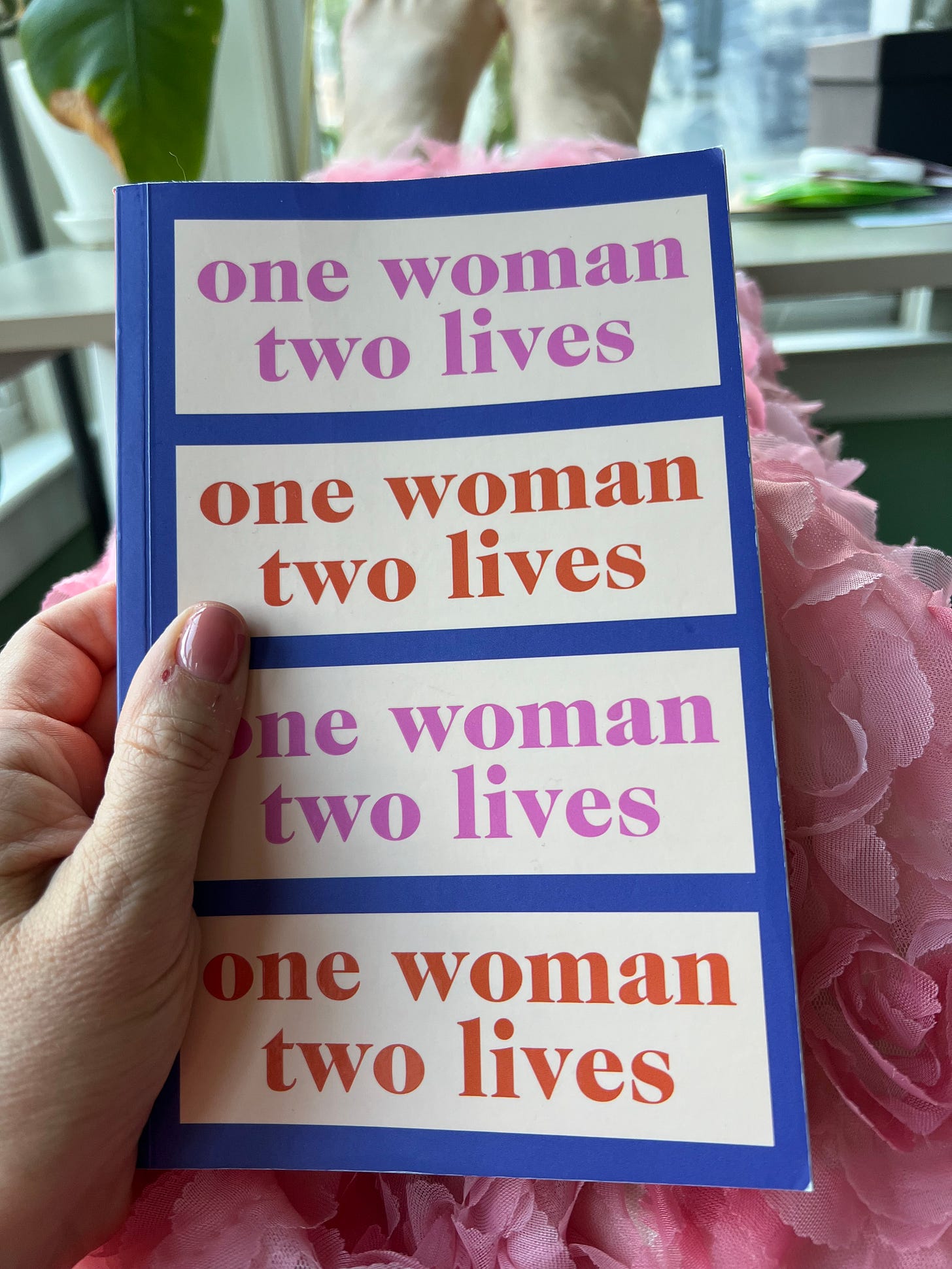

VERSIONS OF A GIRL, Catherine Gray

In the UK, Gray is something of a household name, vaguely along the lines of Cheryl Strayed or Glennon Doyle or Liz Gilbert, for her blockbuster memoirs on getting sober, the first of which–THE UNEXPECTED JOY OF BEING SOBER– and BEING SINGLE, which are now on my must-read list (despite being a person who rarely drinks and has been married for most of my adult life!). In her riveting fiction debut, she virtuosically explores two of the terms that made her name–“unexpected” and “sober”--while also playfully subverting the conventions of plot and structure and characterization that have long defined the contemporary novel. What do I mean, you ask? Well, VERSIONS OF A GIRL employs a Sliding-Doors-style conceit, following one girl over two pathways: In one version, she’s raised in the U.S. by her father, a well-intentioned alcoholic musician whose left behind his noble origins; in the other, she stays with her chilly, striving, well-married mother in London, and forges a more expected path, in terms of career and romance. I’m strenuously avoiding spoilers here, as for me, the unexpected twists of plot provided serious delight–and, at times, gasps of astonishment. So, suffice it to say, there’s a mystery at the heart of this tale, which slowly unfurls in unexpected and satisfying ways, in both versions. This is, at once, a delightful entertainment–written in prose so elegant, at times it made me smile–and a meditation on what exactly makes us who we are, as people. It made me think, much, about how parents shape their children’s lives, both consciously and not. (Or, okay, how I, as a parent, am perhaps shaping my kids’ lives, in both good ways and bad.) Also, I really loved Gray’s list of favorite books for The Literary Edit!

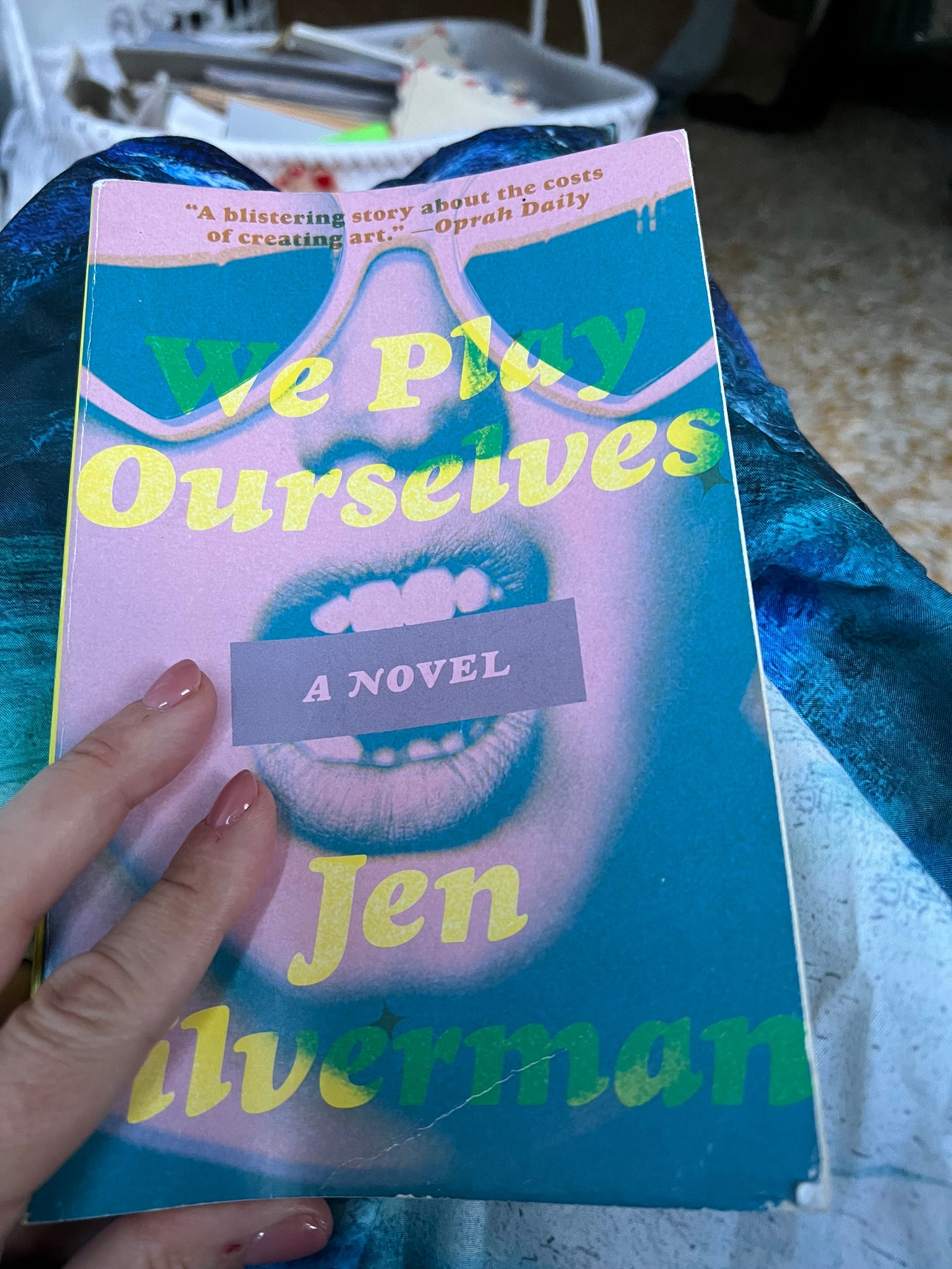

WE PLAY OURSELVES, Jen Silverman

Back in July, I talked about what I think of as “me books,” meaning novels and memoirs with which I feel a direct and unshakable kinship in terms of style and subject matter and, I don’t know, vibe? This debut novel from Silverman falls so resolutely in that category that no less than TEN people insisted I read it, some friends, some acquaintances, some fans, who saw a common thread between the novel and my own books. And they were right! Silverman, like me, is deeply concerned with the intersection between art and commerce, with the economic and social structures that invisibly define our every move, and with artistic friendship and competition. And they write in the wry, urgent style that I love, with dark humor threaded through every sentence. They also write about LA, and the film industry, another obsession of mine–maybe, in a future column, I’ll rattle off my list of favorite LA novels?--with an insider’s eye and understanding (they’re a screenwriter) and an outsider’s sense of absurdity.

As I was reading this one, I kept turning to my husband, Keeril, and reading pieces aloud to him (which I rarely do, because he actually hates it, but indulges me because he is the best) and recounting pieces of the plot, which centers on the theater world, portrayed with both radical accuracy and spot-on satire. The idea is this: Cass, a young–or youngish– playwright, arrives at a friend’s house in LA, following an undisclosed incident that has ruined her previously-burgeoning career and gets pulled into the luminous world of the filmmaker in the neighboring house, shooting a documentary about a teen girls’ fight club. As in all novels of Hollywood–from THE DAY OF THE LOCUST to THE NOWHERE CITY–all is not as it seems, both in the present and the past. And over the course of this buoyant, compelling tale, Cass arrives at an understanding of the world, and herself, reminiscent of the best coming of age tales (restraining myself from mentioning THE CATCHER IN THE RYE here). I loved this novel so much I read it twice.

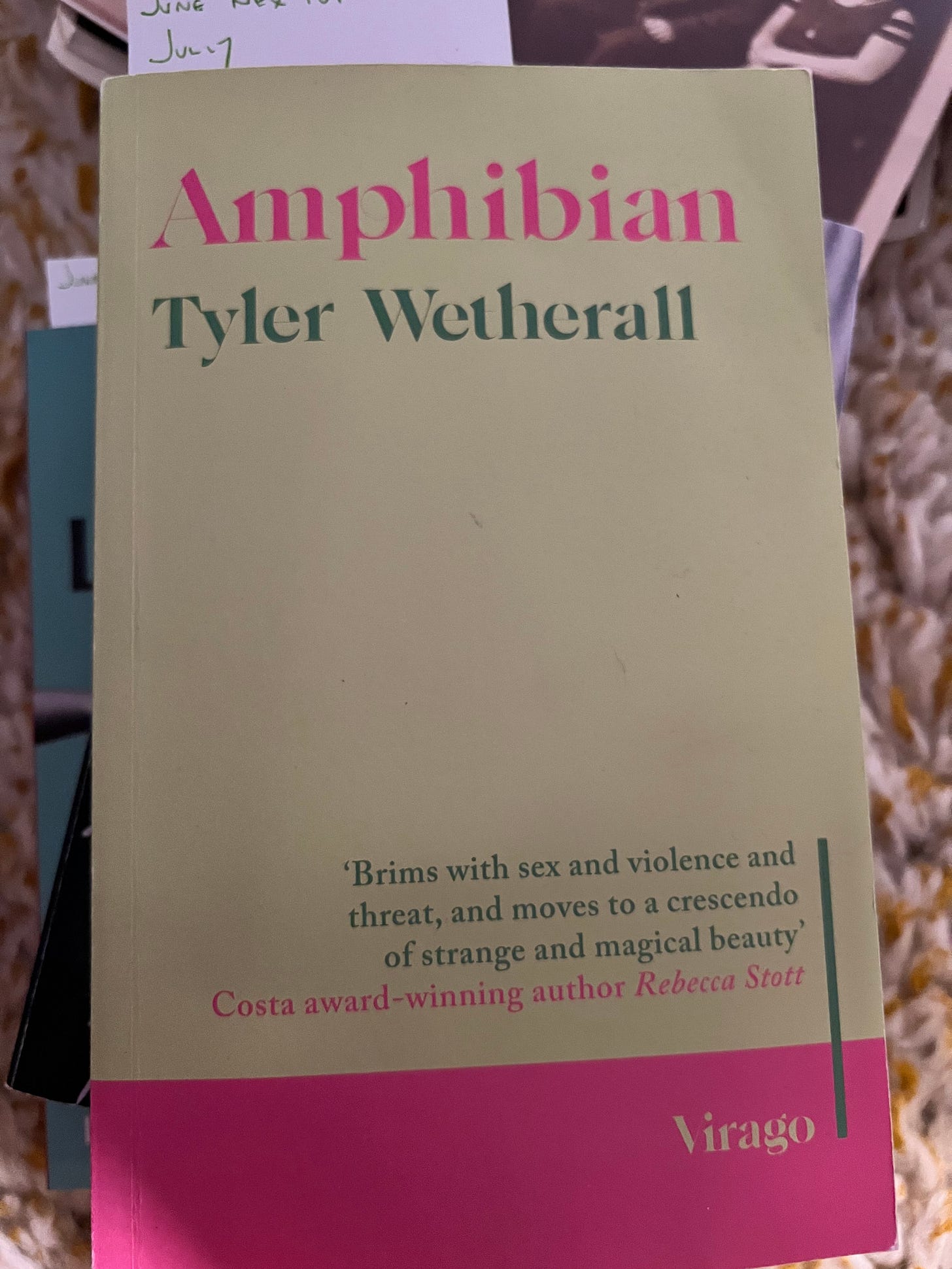

This intense, harrowing debut, from acclaimed English memoirist Weatherall, instantly brought to mind some of my favorite writers–Mary Gaitskill, Jeanette Winterson, Ali Smith–and yet it’s also one of the most singular novels I’ve read in years. Set in the early Nineties, AMPHIBIAN follows twelve-year-old Sissy Sovo over her first year in the West Country–she and her loving, gentle, but decidedly unstable mother have moved, suddenly and for mysterious reasons, from London– as she grows closer and closer with Tegan, her school’s most magnetic, volatile figure. Fatherless and half-Greek–and vegetarian, and quiet-–Sissy, with her dark hair and down-covered legs, is an anomaly in the area; and she’s drawn to Tegan, in part, due to the power she holds over their class, sway that soon shifts Sissy from relentlessly mocked outcast to untouchable popular girl. But Tegan’s allure stems, too, from her pushing of boundaries, her attraction to danger, her anxious desire to see herself, and be seen, as older than her years, to sexualize herself, and bring Sissy along for the ride. There’s so much more than plot to this gorgeously observed novel, and I found myself vibrating with fear and love for Sissy, and also recognition of the girls’ universal longings for something bigger, more meaningful than the small suburban lives they’ve been allotted. And my heart broke, over and over, for Sissy’s fragile, familiar mother, Mou, as she struggles to make a life for herself and her child fully and completely alone. Even typing that sentence, well, tears sprang into my eyes.

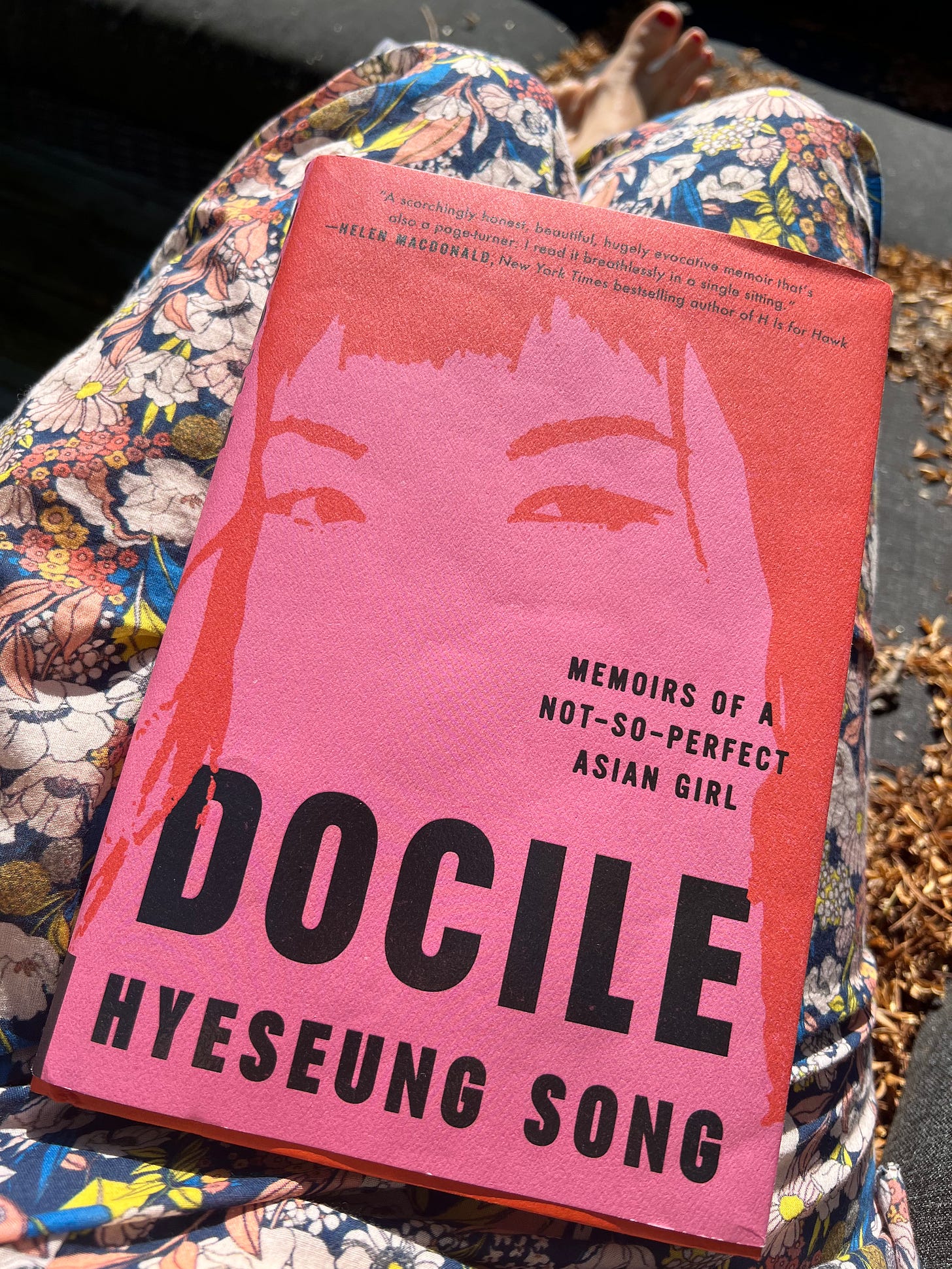

DOCILE: Memoirs of a Not-So-Perfect Asian Girl,

Nearly two years ago, I happened into a panel discussion–at AWP, the enormous annual writers conference–in which Song spoke about working on DOCILE, using singular, unusual, exciting language to articulate her writing process, and her ideas about memoir and narrative, which eschew conventional rules about storytelling and character development and preconceived notions of what a memoir should be. After the panel, I looked Song up and discovered that she’s a painter; and, not surprisingly, her work is iconoclastic, evocative, incorporating techniques and themes and subjects and ideas from many different schools and movements, and, also, deeply moving, in a manner that made me think of a radically diverse group of painters, from Lucian Freud to Valasquez to Rothko.

When a galley of DOCILE hit my porch, I opened it immediately, and found my expectations of brilliance completely met. Told from the perspective of Song now, as an adult, the memoir essentially tells Song’s life story, through the lens of the expectations placed on her, as a Korean-American girl and then woman, and the way these ideas about who she should be, how she should be, divorced her from her own desires, needs, interests, ambitions, her own self. Like the best memoirs–and novels, really–it offers extraordinarily universal truths–I saw myself, over and over, in Song’s tales of her Texas childhood–through a highly specific story, in part due to Song’s finely calibrated prose and ability, or desire, or need to understand and interpret her own life in a holistic, multifaceted manner, but mostly due to her novelistic approach to scene and character and narration, to her roving, curious, compassionate eye. Though she recounts instances of violence and neglect, this is not a chronicle of victimhood or alienation, but of personhood. And its now in my pantheon of favorite memoirs.

READING NOW

SPENDING, Mary Gordon’s 1999 bestseller, about a New York painter who allows a fan–and lover–to become her patron. I’m enthralled by Gordon’s crisp, Didion-like prose, and her heroine’s clear-eyed view of the world.

’ fascinating study of caregiving, WHEN YOU CARE, which provides a radical and unprecedented take on what it means to tend to others.SHORTER READS

I wasn’t familiar with novelist Sarah Braunstein until I read her story “Abject Naturalism,” in a recent issue of The New Yorker, and then…went back and read it all over again, and truly can’t stop thinking about it. Just ordered both her novels!

, however, has long been a favorite novelist of mine and I was really excited to see this new story of hers, “My Twin,” in The Atlantic. Like all her work, it’s bright and funny and dark and perceptive and just so good.OTHER GOOD THINGS, INSTAGRAM EDITION

Are you aware of Books in Films? Which solely exists to brighten one’s day with stills from film and tv featuring characters reading?

For my new book, The Fifth Passenger, I used Blue Violet, a gorgeous collection of photos by Cig Harvey, as a mood board. Her Instagram provides a dose of pre-Raphaelite-inspired magic, often when I need it most.

As we approach the first anniversary of the horrifying Israel-Hamas war, I’ve found myself increasingly grateful for the work of Elinor Carucci, whose photos you’ve surely seen in the New York Times Magazine and The New Yorker.

If you missed my August recommendations, you can find them here:

I first read My Salinger Year over an entire week while house-sitting for two cats. The house I was staying at had a screen door wall with a gorgeous view of lush greenery that made me feel hidden away, and I read almost the whole time in this perfectly comfortable wingback chair with at least one cat curled up in my lap. On the wall close to the chair, there was a framed poster of The Catcher in the Rye’s original cover, and I’d see it every morning, and gaze at it when I would get up to find something to eat. The person I was house-sitting for also had copies of The Catcher in the Rye and Nine Stories, and then I walked to the Annie Bloom’s Books around the corner and found Franny and Zooey. The whole experience felt completely immersive.

I can't imagine anyone thinking of Didion as a "lightweight " since 1969...🤯 Currently doing a deep dive into all her essays.